When I teach introductory classes on lean, I typically start by asking the students what they think the term “lean” means. The answers I get are usually along the lines of “maximizing efficiency”, “optimizing value”, and, most frequently, “eliminating waste”. No one ever says “managing variation” or “eliminating unreasonable demands on employees”.

Like these students, many lean practitioners, even quite experienced ones, believe that lean is all about removing waste. The eight wastes have become the bedrock of introductory lean courses, whether given in a college classroom or as corporate training.

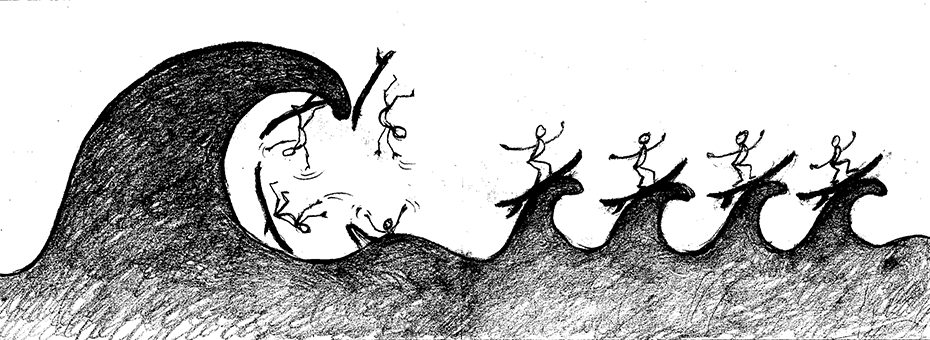

But muda is only a part of the picture. Taiichi Ohno defined not one, but three categories of wasteful practices: unevenness or variation (mura, in Japanese), overburden or unreasonableness (muri), and the more familiar waste (muda). These are often referred to as the three Ms. I feel it’s important to consider all three of the Ms from the outset, because variation often causesoverburden, which, in turn, causes waste. For instance, a sudden spike in customer demand (variation) might cause people to have to work more quickly and/or for longer than normal hours (overburden). Because employees are now tired and rushing to finish tasks, they are more prone to make mistakes, causing the need for downstream rework (waste).

Waste, therefore, is often a symptom of a deeper problem. If we try to uncover the root cause of the observed waste, being the good lean thinkers that we are, we will often find the culprit to be variation.

Working in an office as I do, I see people drowning in electronic “inventory” (muda), multitasking between many different priorities (muri). But when you suggest that they might regain some control over their workload if they knew how long each task might take to complete, they’ll reply that it is futile to even try to measure what they do. “It’s too variable!” they will protest.

They are, in many ways, right. It’s hard to predict processing times in advance when the work is full of mura. You would not ask a mechanic to tell you how much your car repair is going to cost before he has a chance to look under the hood and properly diagnose the problem. Office work is often similarly emergent: we don’t know what we’re getting into until we start doing it. But just because the work can be highly complex, emergent and variable, does that mean we should throw up our hands and claim that there is nothing we can do to make it better?

Before we can measure and schedule our work more effectively, we first have to think about how we can manage mura. Mura is not just about how the demand for turkeys tends to be higher prior to Thanksgiving. When we start to look around our internal operations, variation appears everywhere: there is huge unevenness in priorities, size of backlogs, distribution of the work, number of projects on the go, technology performance, availability of staff, timing of work, individual competency, and quality of data, to name just a few. Are all of these factors completely beyond our control?

One method that can be highly effective in managing mura in office environments is to decouple specific employees from specific customers. The loans administration department in the financial institution where I work, for instance, used to operate with a model that made specific individuals responsible for a certain basket of customers. This model, on the surface, made a lot of sense: customers had a dedicated representative that they could call and count on to handle all their needs, from invoicing and repayments to disbursements and contract amendments. Meanwhile, employees got to know their customers and could be “held accountable” for their satisfaction.

The problem, however, is that specific customers, due to the variation in their own financing cycles, have lots of demands at certain times of the year, and fewer at others. At any given moment, some teams were overwhelmed while others were underutilized. The workloads were unevenly distributed, employees were either overworked or bored, and the service customers received was inconsistent.

As a countermeasure, the director of the group had everyone document their work procedures and then reorganized the teams so that everyone would be able to do everyone else’s job. It took a lot of cross-training, but now every desk has specific, standardized tasks to perform and everyone rotates desks on a weekly basis. Crucially, 10-20% of the workforce is on “floater” duty, meaning that they are available to help out wherever the excessive work demand happens to be that day, relieving their teammates of overburden. And the department has, since 2011, managed to handle a threefold increase in lending volume (in dollars disbursed per employee), while customer satisfaction has remained as high as ever.

The director could have focused instead purely on muda. She could have insisted that employees lower their individual error rate by demanding that they adhere strictly to their standardized work, but she would have overlooked the mura that was driving the errors and much of the employee disengagement in the first place.

We need to bring the two lost Ms of muri and mura back into the basic “Lean 101” curriculum and vocabulary. The great management thinker W. Edwards Deming emphasized the importance of understanding and managing variation, but I encounter few lean thinkers speaking about Deming these days. Why? To me it seems like mura is more fundamental than ever.