Dear Gemba Coach,

I’m a frequent reader of your columns and you always seem to emphasize quality first, but I can’t find many books detailing a lean approach to quality – is this what six sigma is about?

Please! Six sigma is a bunch of (very valid) techniques, but in no way a lean approach. And yes, you are correct. Firstly, there is absolutely a uniquely lean approach to quality and secondly, we are at fault by not writing more about it. I suspect that the simple reason is that it’s hard. Art Smalley and I once started a workbook on “built-in” quality and we failed – quality is very specific and tied to technical processes, which is very hard to write about in generic terms.

Quality is a difficult topic because, as normal human beings, we easily miss outcomes by focusing on outputs. For instance, let’s go to the gemba in a doctor’s office. When you walk in for a check up or because you don’t feel too good, you’re expecting a good outcome: You want to be healed as fast and painlessly as possible to get back to living your normal life. You expect from the doc:

- Accuracy: The most important thing is making the right diagnosis right away and then giving the right treatment.

- Availability: You want to see the doctor right now, not be put on a waiting list, not wait in a room full of coughing, sneezing, grumpy, miserable patients.

- Attitude: You desperately need to trust your doctor, and her attitude really matters. Better a good doctor with a bad attitude than a nice doctor that doesn’t know what she’s doing. But the bedside manner directly relates to how much trust you put in her treatment, how rigorously you’ll take it, and how much the placebo effect will kick in.

- Advice: A doctor that has proven herself to be accurate, available, and trustworthy will be able to give you life advice that you will value (stay off those fats, exercise more, wash your hands before eating) and that will enhance your health level beyond the immediate problem you walked in with. (Alternatively you’re likely to reject perfectly valid advice from a doctor you dislike.)

The four As of Accuracy, Availability, Attitude and good Advice describe a patient outcome. The doctor, however, has a slightly different problem as in an endless queue of patients to see and bills to pay. So it’s easy for his focus to creep into output: how many patients treated in one day, focus on less than 10 minutes per patient, and just get the job done. In doing so, the doctor might be seen as efficient but can easily lose effectiveness. Diagnostics are too quick, prescriptions are generic, interactions are dismissive, and learning stalls completely.

Getting the Quality “Click”

Toyota’s unique take on market share is customer satisfaction through highest quality, lowest cost, and shortest lead-time.

What does highest quality mean in practice? This is often very tricky because products and services can be seen as:

- What all products and services have in common (a car is a car is a car that gets you from A to B and runs on gas)

- What some products and services have specifically that customers really, really like.

Quality is (1) perfect accuracy on what every one has in common, since a failure there is perceived as an annoyance by the customer and (2) offering something special; hard to quantify, but that makes customers smile – and weds them to your brand.

I was on the gemba a few days ago looking at the lean engineering efforts of a company that makes skylights for cars – inserting the glass in the roof with all the machinery to open and close, shutters and so on. We were looking at a new concept paper and the engineer has identified that the mechanism had to:

- Work easily and not break down – this is basic value all competitors will offer (to varying degrees)

- Make the right sound – this is a unique insight that, as with car doors, there is something uniquely satisfying to something that closes with the right “click.” I doubt there is a word for “nice close” but this is definitely something that makes you feel “hmmm” with a hint of a smile.

The future will tell whether the engineer hit the right spot, but he’s trying – accuracy in basic performance and attitude to provide something more.

Quality and Kanban

Toyota, for instance, beyond making cars that perform like any other competing cars in a price range, has created its market share on, first, “peace of mind” and second “energy efficiency.” On the way back from the airport, the taxi driver told me that he now drives a Toyota Prius because his cherished Mercedes was too often at the garage, whereas he never had to worry about the Toyota and secondly, spending as much time as he did on driving in town, he did see a visible difference on his gasoline spending. And he felt good about polluting less. (By the way, the competitive pressure this puts on the market is real, as the recent VW scandal shows). Other automakers have chosen style, power, or comfort.

Once you’ve sorted this out in your mind, the question is how do you deliver it. Have you seen the wonderful BBC Top Gear program about “how to kill a Toyota?” It’s a fun illustration of how peace of mind is engineered. What is the unique lean approach to doing so?

The trick lies in understanding that quality is both accuracy and availability. By shortening lead-times, Toyota puts pressure on exact delivery of only quality parts at all levels. If there’s any doubt on the quality of the part or its assembly, the line stops – but the pressure on delivering small quantities at regular time intervals remains, so investigation happens right now! In other words, we’re seeking high quality, immediate delivery without excess inventory – in order to be able to focus on every single part and spot delinquents right away (as opposed to inspecting a full batch of waiting parts).

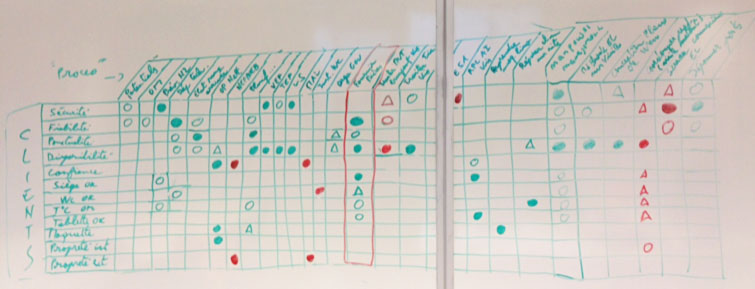

Built-in quality means that we can draw a mental matrix of:

- The main functions we offer customers and their expected performance level

- The logistics of delivering this function (in products, this means not just the module that delivers the function to the customer, but that creates the module).

From the gemba, here is an example (above) of one such matrix for a train service center. On the left-hand side, you find the customer benefits, and on the top the processes delivering these benefits. Filled circles are the high interactions; red circles are the ones where kaizen is currently going on:

Thorough just-in-time on each basic process will surrender endless internal quality problems that are each an opportunity to improve the accuracy of the whole product or service while we’re improving availability as well. No inventories mean that the single part (oh, okay, five parts) that we have on hand are all good.

An obsession for few parts all good in each process that delivers performance to customers has deep impacts on engineering either the product or service. First we’re going to be a lot more careful about changing things. Yes, product must evolve and innovate, but not at a risk to quality. The Chief Engineer wants to put all the most innovative features in the new car but has to care for standards – this will lead us to define very early on what moves and what does not.

Second, the emphasis on constant training now becomes obvious. Few parts of everything all the time means that the five components you have on hand are all good (there’s no inventory to rummage for a good part to replace a faulty one). It means that the effort to make sure the process that delivers them works perfectly is a necessity; not a “nice to have.” On the one hand we change less stuff, on the other we work a lot more to make existing processes work. The key being, of course, kaizen.

Lean as a Quality System

Which is another reason we find it hard to isolate quality (contrarily to six sigma and similar approaches) from just-in-time in our descriptions of lean – quality is the prerequisite to kanban, that’s quite obvious in all the old Toyota textbooks, but quality is also achieved through kanban: the smaller the batches, the less parts in the process, the higher the pressure on quality. You can’t separate them.

If we look at it at individual level, how do we expect anyone to master any task:

- Outcome: Can the person deliver the right quality autonomously (without help or correction) every time?

- Output: Can the person deliver the right quality within the target cycle time autonomously (without help) every time?

- Ideas: Does this person have ideas to make the standard easier to follow and thus increase chinches of delivering outcome and output?

- Teaching: Can they teach others?

For a new line, at start of production, takt time is a key aim and the question is how fast can we reach takt time:

- Every product has to be right, so it’ll take the time it takes to solve every quality problem as they appear step by step on the line (which means learning to detect them as close as can be to where they are created).

- As quality issues are mastered, we get closer to target cycles time and thus closer to delivery at planned takt time.

- When takt time is achieved regularly we either take resources away from the line or add a new product to keep the kaizen spirit alive, and start another cycle of solving the quality problems that appear, and then reaching the target cycle time again, and so on.

Toyota has very clearly taught us that in order to achieve customers satisfaction (highest quality, lowest cost, shortest lead-time) we need to master simultaneously the twin pillars of just-in-time (takt time, pull, and one-piece-flow) and jidoka (stop at defect and make machines autonomous on quality to separate machine work from human work). These twin intents (increased just-in-time, increased jidoka) drive the real work of kaizen and evolving and maintaining standards, which will deliver quality in terms of accuracy, availability, attitude and, in the end, advice.

Yes, as lean authors, we are remiss in not explaining the quality dimension of lean thinking better. No doubt about that. The only help I can suggest is for you to try and see the quality aspects embedded in all just-in-time discussions and, yes, emphatically yes, quality comes first, then delivery, then lead-time reduction, then cost reduction. Still, this is counterintuitive. Conditions to increase quality are created by our efforts to improve the precision of delivery, reducing lead-times, and reducing wasteful costs. It’s a system.