I received the gift of lean in 2007 when I was a frustrated store manager for Starbucks Coffee Company. Not only did lean give me hope and a way to help my store team, but it also illuminated a path for personal transformation that, in turn, I could light for the rest of the company. And now, more than fifteen years later, I get to share that beacon of hope with you.

I told my personal story at LEI’s Summit last month, expressing gratitude for my good luck and encouraging the folks in the audience to pass it along to as many people as possible. Afterward, two people came up to me with essentially the same comment. They said, “Please recognize it was much more than luck. Many people are given the gift of lean, and most of them do little if anything with it. So, don’t neglect what you had to do in receiving it and putting it to use.”

Fair enough. I accepted lean when someone presented it to me. But as I reflect on the feedback that it was more than just dumb luck, I’ve come to believe that the “flavor” of lean I received was the most important factor.

In other words, what mattered the most was that I was given the enabling, clarifying, and supportive “flavor.”

What about you? When, where, and how did you receive the enlightening gift of lean? Perhaps most importantly, what “flavor” of lean were you given? And, more generally, what do you think makes lean the gift that keeps on giving for some, like it’s been for me, yet something others choose to ignore if not reject outright?

Experiencing the ‘Right Flavor’ of Lean

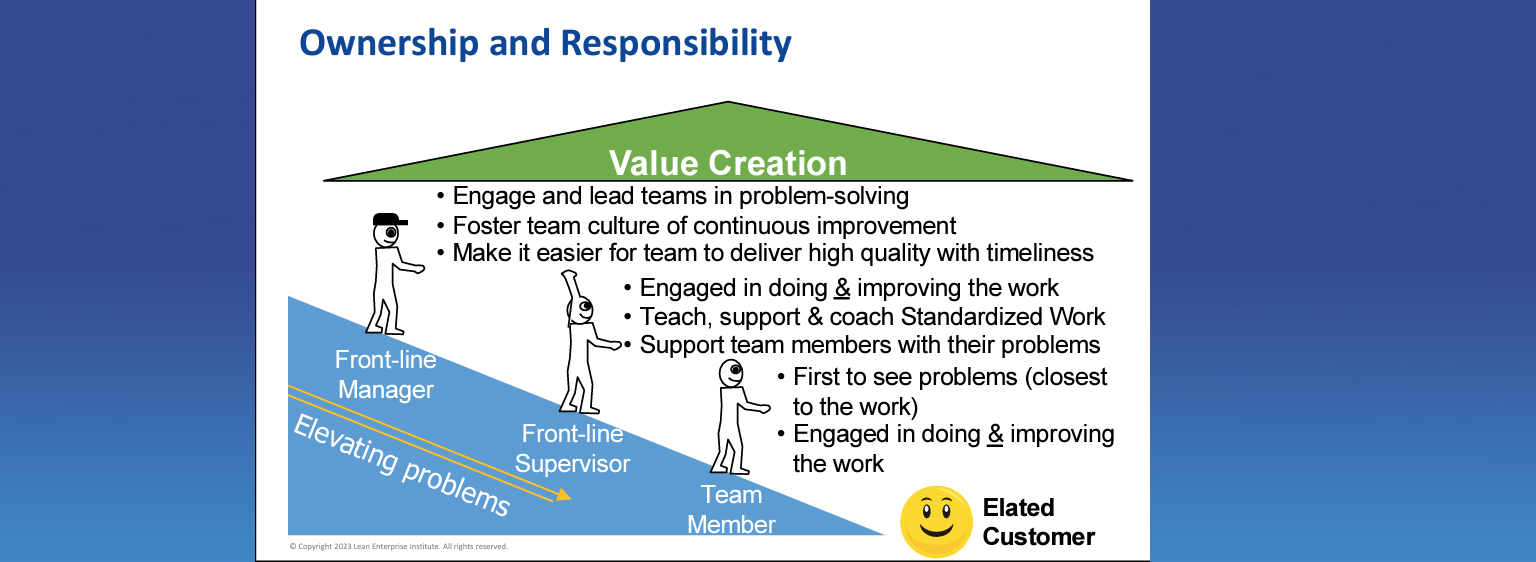

As you mull that over, here’s more detail from my lean origin story that I shared at the Summit. It includes the context around when I received the gift, which also mattered, and elaborates on the lean management system my lean leader helped me to adopt. That system put me and my team — the value creators — at the center, provided clarity to the purpose and value we were there to create, and enabled us to solve problems in the work that creates that value. That system also supported us when we needed it, with as much or as little support as was necessary.

After the leadership team experimented with how to make improvements in the company’s coffee roasting plants and headquarters, they randomly selected my store to conduct the company’s first experiment using lean to improve in-store operations. At the time, our sales growth was consistent, with a predictable 20% increase year-over-year. Starbucks could print money in those days, despite managers with little experience and no methods for improvement like me.

My training included lots of pictures and examples from factories. So, I did my best to translate ideas from car plants to coffee shops when I delivered the training to my store team. (Translating lean into non-traditional contexts has become something of a career-defining capability.) Lean in retail and food & beverage was new back then.

Ultimately, we received clarity by learning to “see” from the customer’s perspective and framing problems in terms of quality, friendliness, speed, and cleanliness. We defined quality using concrete product standards such as temperature and taste (e.g., creamy). Moreover, we further specified the “Starbucks Experience” using behavioral standards such as “make eye contact” for friendliness, timing standards for speed, and visual standards for cleanliness.

Once we aligned on these standards, our lean leaders helped us develop our lean capabilities, enabling us to improve our work by removing waste and striving to exceed our customer’s expectations. This training and coaching led us to discover a slew of improvements that demonstrably increased customer satisfaction, reduced costs, and made the work, which now included solving problems and making improvements, easier and more fulfilling. It was incredible!

Setting Challenges, Respectfully

And frankly, for me, it needed to be. You see, lean nearly missed me. After a few years with the company, I was starting to check out. You could say I was “quiet quitting,” fifteen years before it was cool! While I still enjoyed the people I worked with and the buzz of a busy morning when everything’s working is downright addictive, my experience was that things often didn’t work. And the “solutions” we got from The Building (the internal nickname for Starbucks headquarters in Seattle, Washington) rarely helped. “What do they know?” we’d ask ourselves.

But in that “model line” experiment, lean was making me responsible for a problem-solving culture within my store. It challenged me to “put up or shut up.” It asked me, “Well, what do you know? What are the problems to solve? What’s the company’s direction for improvement? Is the team aware and do they agree? And then, what’s really going on in the work? What’s causing things to go sideways?”

Creating A Support System

I wasn’t just empowered and left alone, however. The lean system also gave me a support network. First and foremost, there was my manager who was learning to lead as a coach. And secondly, there were “support staffs” for systemic problems. For example, the local equipment group launched a preventative maintenance program to address long-standing issues with equipment reliability. The idea was that support staff, including the equipment group, would help as often as needed and as seldom as possible. Because we — the store team closest to the customers and the work — would own most of the problems. And damn right. Lean thinking and practice was giving us a way to figure out how to make things better. Seriously, it was incredible!

Experiencing Lean’s Antithesis

At the same time, my store was an island off the mainland of the way things had always been. I’ll never forget when a top executive visited to see what we were doing. We were excited and nervous. When he arrived, he spent ten minutes outside the store chastising a group of managers. We later learned he’d seen a few cigarette butts in the parking lot.

When he finally entered the store, he looked around, then turned to me. Without introducing himself or asking my name, he asked if I was a rebel. Like an idiot, I said, “Yeah, kind of.”

… given the changes we’d been making, I did feel like a rebel! I felt empowered to make things better for customers by any means necessary.

The truth was, given the changes we’d been making, I did feel like a rebel! I felt empowered to make things better for customers by any means necessary. For example, we rearranged the espresso bar’s layout and replaced the large milk-steaming pitchers with smaller ones. We were making drinks one-by-one instead of in batches, which we learned, improved beverage quality by, among other things, reducing lead time. So, in a sense, we were “rebelling” against the way things had always been.

The changes we made, however, were not random brainstorms. We weren’t simply “empowered.” We based the changes on facts about value and the work that we had learned to collect from the gemba. So, equipped with tools for lean thinking and practice, we could make a big impact. Results were demonstrable. The changes were undeniably “good.” We knew this to be true. Not everyone did.

The reason the top executive had asked if I was a rebel had nothing to do with what we were doing. You see, he had noticed what he mistakenly believed was out-of-date signage in the merchandise area. Because merchandise sales made up about 3% of the top line, he assumed I was refusing to remove it. However, that was not the case. While he had earlier decided to remove the signage, the corporate staff had not yet told the store managers of the decision. Anyway, thinking I had screwed up, I immediately removed the signage. A week later, I received an email telling me to remove the signage. Anyway, the visit was not off to a good start.

He kept looking around — at signage, cigarette butts, or whatever — while we tried explaining how we were seeing things differently now. We tried sharing our newly acquired insights into the “customer journey.” We talked about long wait times, product stock-outs, the frequent need to repeat orders, inconsistent quality, and friendly service and clean stores only when things were going well. He kept looking around.

At one point, he repositioned a coffee mug on display, ensuring the handle pointed perfectly to the right (per the merchandising standard). We tried showing him the changes we were making in our work. We tried explaining how we’d improved quality and reduced wait times. While ignoring all that and repeatedly asking about sales, he wiped his finger on a slightly dusty shelf. Then he held it up for me to see. We could both see the dust. Only one of us, however, could see the work. And only one of us was focusing on what our customers actually cared about, 97% of them anyway.

Weathering a Downturn

And then the 2008 financial crisis hit, causing sales to reverse direction and shrink seemingly overnight. The truth was, and still is, Starbucks is a luxury brand. You don’t need a $4 Mocha. Your kid doesn’t need a $4 cake pop. A teenager doesn’t need an $8 Frappuccino. (I’ll never forget, across the street from Starbucks headquarters, McDonald’s put up a billboard that said, “Four bucks is dumb.” It was hilarious!)

People who lost their jobs and saw their home values tank stopped going to Starbucks. Perhaps you remember the headlines: Starbucks closing stores, Starbucks laying people off, Starbucks burning through its cash. Suddenly, it seemed, we had to start earning our remaining customers’ business every time they visited. This requirement was new for me, as it was for nearly everyone working in stores across the company. But on our lean island, my team was relatively less worried about this new challenge. We had lean to guide us along.

Recounting an Effective Lean Leader’s Behavior

Fortunately for the company, its head of global strategy Scott Heydon brought lean into the company, knowing how much improvement potential there was in the customer experience and the business. He was leading and deeply involved in the lean experiments in the supply chain, corporate processes such as marketing, and now in stores like mine. Even better, he worked as a barista in his neighborhood store on Saturdays, the busiest day of the week.

Scott gathered firsthand insights into customer problems and supported specific improvements such as rearranged workstations, different tools, and process changes. Moreover, he was learning what it would take to realize the stores’ potential, including the need to focus on value in terms of the customer experience, dig into the work to improve it, bring leadership closer to store teams to help them solve problems in their work, and establish a support system to deal with systemic issues. In essence, to do all that was needed to make baristas successful: Engage everyone, every day, in making things better.

Achieving that ideal for tens of thousands of stores worldwide versus one store in Portland, Oregon, became his challenge, his high-level problem to solve. And this work helped launch an enterprise-wide lean transformation. Scott assembled a “lean team,” hiring me and a few others from Portland to spread what had worked in a few stores to all the others. We sought to influence leaders like the top executive who had visited my store. We needed to help him, and others like him, focus on value for the customer; see the work, its waste, and the necessary changes; and then to understand his role as an enabler of a problem-solving culture, where the right people at the right level solve problems.

Name-calling and dusty finger-waving would have to stop.

Building a Lean Operating and Management System

Gain the in-depth understanding of lean principles, thinking, and practices.