Dear Gemba Coach,

What personal qualities should I work on to improve how I practice lean?

Intriguing question – really made me think. Are there specific qualities to practice lean? I would have said, “No, not particularly,” but thinking back at last week’s gemba walks and people’s various reactions, maybe there are.

Let’s backtrack and think back to how lean thinking operates and what it is that makes it deliver performance results.

The starting point of lean is accepting we don’t know what the correct answer is and putting the customer’s point of view first – we, therefore, try to understand better what is going on for real by:

- Pondering the purpose of our job.

- Actively looking for how we could bring value closer to customers.

- Seek out the bad news first.

- Use lean tools with the teams at the workplace to understand more clearly what problems really are: where is the waste? What stops people from doing a good job easily, first time? Why?

- Encourage them to try one change to make things better.

- Think deeply about what happens when they do, ask why?

- If early results are positive, think what needs to be squared out with the rest of the organization for this new way of working to stick (and get people to talk to each other and work it out).

- Challenge people on their next step to spot initiative and encourage growth.

An Example from the Gemba

For instance, a group of senior managers was discussing losing sales because of increasing production lead-times. Although with large, complex special machines, customers traditionally accepted long lead-times and delays, the situation was getting so bad orders were being canceled.

On the shop floor, they could see many machines half-completed with no one working on them and a few people working here and there. The discussion led to asking the question, “How can we change from a lot of machines in the shop and few people to a lot of people and few machines?” This opened a heated discussion with the site management, which finally established that not only recruiting skilled workers was a real concern, HR processes made it almost impossible to do so.

As the CEO kept digging for the bad news, what finally turned out was that the HR labor budget had been established at a low activity period (although it was known that the peak was coming since all the projects were in development), and so the people budget was low. All the pressure from corporate was on making people productivity gains, not getting machines out of the door – hence the situation at hand.

Obviously, this discussion did not happen easily and coolly as there were many other bad news items, such as suppliers late with components, engineering flaws needing fixing, and the usual mixed bag of issues. But nevertheless, by not letting go, the CEO did get everyone to realize that even if he personally ordered them to double the operator staff today, the company had no concrete way to do so.

The first quality I see here is curiosity.

During the discussion, accusations and defenses went back and forth. Then managers pushed for their solutions, mostly from the hip and half-baked … and predictable. The CEO stayed with it. He didn’t have a solution. He was actually curious to figure out what the issue really was.

Eventually, he moved to a machine where two technicians were actually working together on assembling a difficult component. He asked the lean officer for a tool to observe work.

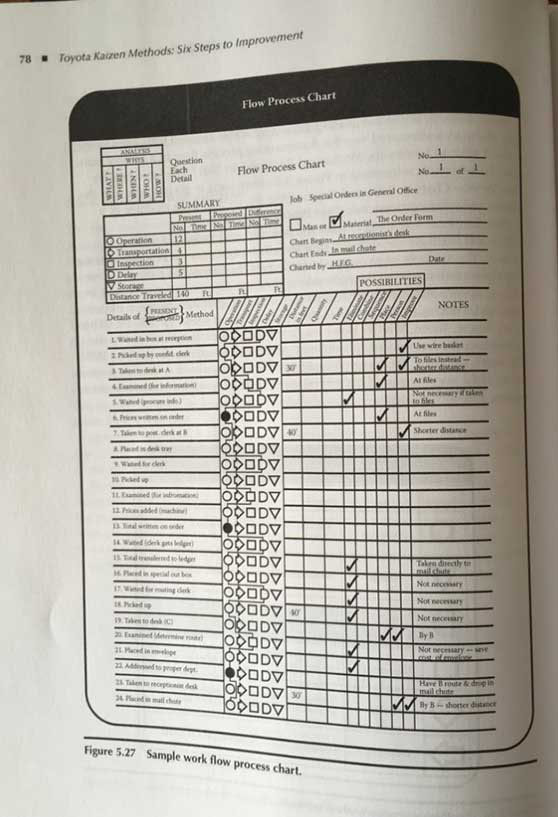

The lean officer had the presence of mind to recreate on the spot an old flow tool, similar to what can be found in Isao Kato and Art Smalley’s Toyota Kaizen Methods.

Simply Curious

Splitting the management group into three pairs, the CEO asked each pair to go and observe how assembly really happened.

The pairs of managers started drawing their flow charts, but very quickly they got sidetracked into discussing their own issues rather than continuing to observe. When the CEO asked them to reconvene, he was irritated at the paucity of the actual observations, but grit his teeth and said nothing.

What he had realized is that the work was so imprecise, riddled with false starts, rework, looking for tools, and so on that even if he forced more people on the shop floor they would not know how to work together on the machine. All you’d get would be, say, three people assembling a machine, but still waiting their turn and working one after the other – not going much faster than one person.

In the end, the CEO asked the lean coach to grab the two best operators and ask them to think about how to work together to accelerate completion time. The lean coach suggested he could start filming repeatable assemblies and ask the guys to work out a way to do it with two people so that both could make the work progress. The CEO thanked him and asked him to schedule a gemba walk two weeks from there to see progress.

Thinking back about the whole episode, the managers just wanted to come up with a solution, decide on an action, and move on. The CEO was simply curious – he wanted to understand what was going on.

“Something-ness”

Secondly, as he analyzed the work, he immediately saw the time lost looking for the right tools, the screws hard to assemble, the “normal” rework as the operators struggled with assembly after assembly, or not understanding the blueprint and so on. Yet, he didn’t jump on the first obvious solution (“let’s do some 5S”) but actually followed through the exercise to think deeply about the work and isolate factors.

Finally, he came up with a very concrete solution – relying on the team and asking them to come up with something.

The other qualities we can see beyond curiosity would be:

- Patience (or impatience with the quick, obvious answer).

- Follow-through.

- Pragmatic confidence in the shop-floor team’s “try something–ness” if there was such a word.

The qualities of lean thinking aims to develop are well known: 1/ the courage to go, see, and face unfavorable information, 2/ better judgement, 3/ quick decision-making and pragmatic, immediate experimenting – and changing one’s mind according to what others show you, 4/ the ability to bring people along, to engage and inspire them in order to draw out their initiative and creativity. These qualities are easy to see from the outside, but what makes your question so interesting is that subjectively, it’s hard to see how one can set about developing these four qualities in oneself.

On the other hand, I believe you can set yourself the project of being more curious:

- Wanting to understand what goes on as opposed to wanting to do something quickly to make the problem go away, Having more patience or persistence (taking the time to really figure things out by mulling over a topic rather than being content with quick, stereotypical answers),

- Working with one’s teams rather than doing the analysis and conclusion oneself and then assuming others will execute,

- And finally having the resilience and discipline of follow-through topics, even when they resist and do not deliver instantly.

In most work environments I know, delivery has become the only topic of discussion and time-pressures are such that there is simply no space for discovery. Yet, discovery is about asking oneself “are we solving the right problem” rather than jumping on the first satisfying solution and moving on to something else – which is exactly what the management team directors were doing.

Deep thinking is what the old-time sensei used to make us do. This, I believe is more important now than it was then. It sounds really silly to advise you to just “think more deeply,” I agree, but there it is. As a first step, I truly believe that developing and looking for curiosity is probably the most valuable thing one can do on the path to deeper thinking.