Dear Gemba Coach,

I’m currently a team leader, and I’ve been offered a job as a lean manager – what should I expect?

Oh, well, this really depends on what kind of organization and what type of lean your management is practicing. For argument’s sake, on the gemba, let’s split this into two situations:

- Operational excellence: The CEO has delegated to one of her execs a program to generate savings or improvements.

- Lean transformation: The CEO is working with a sensei to spend more time on the gemba and change how she runs the company.

These are two extreme conditions, and the role of a lean manager differs widely.

In the first case, operational excellence, your success metric is to deliver “improvements” -sometimes measured by dollar savings, sometimes more vaguely as solving someone’s problems or making a process perform better.

Your job is that of an internal consultant or coach; you have to learn the tools in the lean toolbox your company uses, find team leaders willing to experiment, and coach them through getting some visible results – and make sure you track their progress because ultimately, this is what you’ll be evaluated on.

In this case, you need to practice three main skills to succeed:

- The tools: There are many tools in the lean toolkit, and the company program usually highlights a few more than others, but that’s still a lot to take in on the gemba. Pick a few tools, and study them intensely both by reading everything you can find about them and practicing repeatedly at the workplace. There is now ample literature on most of the classic tools, and people will expect you to know what you’re talking about.

- Persuasion: Negotiation and persuasion are key parts of the job. You need to persuade the team to take some time off from their daily work to take up an improvement topic. You need to persuade the team leader that this is going to be good for both their team performance and them personally. Then as the going gets rough, you need to persuade the team to keep going until you have something to show for it. This means constant negotiation with the team (and its management) and constantly trying to convince them to keep at it. No one is typically prepared for that part of the job, so start your own reading program on persuasion and negotiation, it will make the difference between success and failure.

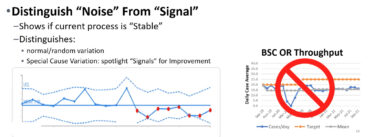

- Metrics: Does a tree falling in the forest make a sound if there is no one to hear it? The third critical skill for an internal lean coach is to be able to handle the reporting system and make sure the coached teams have results – whichever way these results are tracked. These need not be business results (notoriously hard to achieve), it can be process results. Anything. But you must learn to understand how internal reporting systems work and what executives look at – something no one ever tells us about.

Fun but Rare

The attraction of such roles comes from the – healthy – desire to help people and the – deluded – belief we can, from the outside, fix their processes. Certainly, helping a good team with a good team leader systematically think through an aspect of their job that they haven’t looked into before will help them – no argument there. And this makes the job fun and exciting.

But it’s also relatively rare. More often than not, teams get involved with the program with all sorts of political reasons, use the opportunity to either follow red herring issues or show how hard their work really is and the lean coach gets dragged into “saving” them – which no one can. The main risk then is to find yourself between a rock and a hard place, protecting the team from executive pressure while at the same time having to persuade the team to get with the program. This is not definitely not fun.The attraction of such roles comes from the – healthy – desire to help people and the – deluded – belief we can, from the outside, fix their processes.

If your leadership team has in mind an operational excellence program, learning the tools in the toolbox is not enough, you need to learn how the politics of these programs work as well, because if not it will bite you. And confront your own desire to “help” teams that, mainly, haven’t asked for it.

In the second case, the CEO is working with a sensei to transform how she manages the company. This is a completely different ballgame. In this situation, the CEO has understood that performance is overall driven by kaizen energy: Voluntary solving of customer issues, team process improvement, and individual creative suggestions that lead to strategic insights at the leadership level.

In this scenario, the CEO has typically committed to a program of gemba walks to look into how teams:

- solve problems,

- practice kaizen,

- implement suggestions.

The juice to get things done no longer comes from you, as a coach, but from the executive line that needs to deliver concrete examples of what the CEO is asking for, which is essentially:

- implementing visual management, mostly just in time,

- demonstrating voluntary team involvement in improvement.

The lean manager job is then very different – it’s no longer a coaching job, but an operational one: How to make sure CEO’s gemba walks are successful by having the teams ready to present. The emphasis is no longer on cajoling teams to do something or teach them how to solve problems – which is their management’s role – but making sure they can clearly present what they’ve done. This essentially involves helping the team with visualizing their daily management problem-solving board, kaizen QC stories, suggestions follow up, and visual management.

- Daily management: When leaders come to any workplace, the first question in their minds and the first item for the team to discuss is: How is the business doing? Teams are used to reporting to their own middle management but rarely are prepared to speak to the top dog, who has a completely different understanding of the business as a whole. The first thing to help the team with is daily management; what is the critical output measure, how daily changes are handled, how does the team communicate in daily huddles and so on.

- Problem-solving: The next item on the agenda is looking at which problems the team takes up on its own, and how they go about solving them. Here again, if problems are presented clearly and visibly, you side-step the long, awkward, sometimes awful discussions around getting the team to speak up. A typical board produces wonders:

|

Date |

Problem |

Cause |

Countermeasure |

Impact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- Team kaizen: Here as well, visualization is all. Kaizen is not your responsibility, but management’s. Where you can really assist is in helping the team with its storytelling, whether on an A3 or a Quality Circle story. The easiest format is probably:

|

|

Kaizen topic |

|

Gain opportunity |

What concrete gain are we after? |

|

Analysis of current methods |

Step-by-step analysis of what we’re currently doing and where it goes wrong |

|

New idea |

What is the thing we want to try? |

|

Testing of new idea |

Who do we need to convince and how? |

|

Implementation of new process |

Once we’re clear on what we want to change, how do we get the organization to do it? |

|

Evaluation and standardization |

If it works after a while, what else do we have to change so that the new process sticks? |

- Creative suggestions: Similarly, the trick here is to help the team leader show how individual suggestions are taken into account and supported all the way to concrete implementation.

- Visual management: Probably the most technical part of lean, and where middle managers will ask for help – or, more likely, for someone to do it in their stead. But here again, in a lean transformation, physical visual management is management’s job, or else it’s all for nothing. Knowing all there is to know about visual management is important obviously as lean transformations hinge upon the right visual management, but as an auditor more than a coach or implementer. If not, management will take the easy way out and delegate it to you.

Coach or Squeeze?

Setting up the ideal gemba walk is a very different job from helping teams to deal with their problems and/or improve. In my experience, the former succeeds (if the CEO and the sensei succeed) and the latter eventually fails (after early, low-hanging fruit results). In real life, one always does a bit of both, clearly. But we need to take stock of how fundamentally different these approaches are: One is a coach to teams to protect them from senior management (or to squeeze them for results to bring to senior management) and the other is an assistant to the CEO and sensei to create a successful program of gemba walks supporting kaizen initiatives.

Oddly, one learns a lot more about lean in a CEO/sensei driven program, mostly because they teach you first, the business, and second to handle the {typical problem à improvement exercise à insight and initiative} sequence which is so hard to discover on your own, working with teams who have their own agendas and rarely much of a perspective on the business as a whole.

There is lean, and then there is lean. Consequently, there are lean manager roles – and there are lean manager roles. The idea that a lean manager can both advise a team on what the leader and the sensei expect (here’s how you crack the exercise they’ve set up) and support the team in preparing for positive gemba walks for the CEO – success builds on success. One needs to understand which problem we’re trying to solve: a program of productivity improvement workshops to deliver savings, or a program of gemba walks to deliver ideas and voluntary engagement in trying new ways of satisfying customers. The type of program you find yourself in will determine what your goal posts are and how you will go about reaching them.