Dear Gemba Coach,

I’m new to lean and reading all I can find about it, but is there something specific I need to look out for; is there something I should know that I won’t find in the books?

“Visualization” means “materialization.” What we commonly term visualization in lean is, in fact, materialization: turning abstract ideas into concrete objects that can be manipulated and thought about in concrete reasoning, which implicitly accepts the specific differences from one case to the next. Thus, one-piece flow is essentially about looking at parts one at a time, as specific things and not a generalized concept of “a part.”

One of the many reasons it’s hard to learn lean without a sensei is that lean thinking teaches you, well, a way of thinking both at the abstract and concrete levels.

You’ll find all you need (and more) about abstract lean thinking in the books: lean principles, such as jidoka or just-in-time; lean problem solving methods, such as plan-do-check-act; lean values, such as genchi genbutsu; kaizen, teamwork, and respect; and many texts are dedicated to “lean is a philosophy” in some shape or form.

Abstract thinking is all about generalizing concepts and disconnecting ideas from the specific object. For instance, when executives discuss their products or services, they don’t mean any specific object, as in this product now right here in front of us, but some generic idea of what the product is. Abstract reasoning mostly involves seeing relationships between categories. For instance, whereas “this stone thrown in this pond sinks” is concrete, “any object with a density greater than the density of the liquid will sink” is abstract reasoning.

Obviously, abstract reasoning is a very valuable – and powerful – skill, and highly valued in Western society. Most of higher education consists of teaching abstract thinking in a variety of domains, from medicine to finance. In lean, techniques such as value-stream mapping are typically supporting abstract reasoning – such as “factory physics” on how to improve flow.

Look with Your Feet

However, lean practice is also very much focused on concrete thinking. In Taiichi Ohno’s terms: Look with your feet, think with your hands. Genchi genbutsu is a way to avow “facts” (concrete, firsthand, here and now) over data (abstract, generalized). TPS’s founders implicit assumption is that in both engineering and production concrete thinking can be a powerful key to understanding. Rather than reason from abstract problem solving to applying specific solution, they consider that repeatedly solving a concrete problem is the way to solve an abstract one empirically rather than logically.

This, it turns out, is a very powerful aspect of lean thinking. The foundation stone of empiricism is David Hume’s investigation of induction: how many instances do we need to experience firsthand before we allow ourselves to infer a causal connection? Empirical thinking is very different from logical thinking because “logical” connections are only considered valid if there are empirically – concretely – tested.

This, it turns out, is a very powerful aspect of lean thinking. The foundation stone of empiricism is David Hume’s investigation of induction: how many instances do we need to experience firsthand before we allow ourselves to infer a causal connection? Empirical thinking is very different from logical thinking because “logical” connections are only considered valid if there are empirically – concretely – tested.

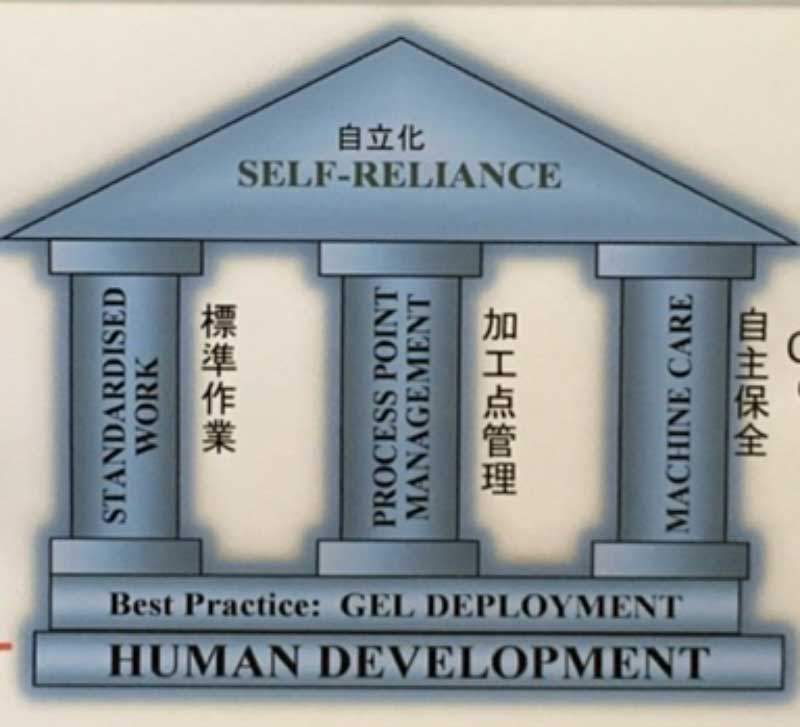

In lean practice, concrete thinking is represented by the “process point” – the physical point where a specific tool touches a specific part. Is the hole cut exactly the same way? Or do we see minute differences from one hole to the next. This “house” from Toyota Australia showcases the importance of concrete thinking.

Contrary to most firms that value abstract thinking over concrete thinking, Toyota is unique in emphasizing operator-level thinking, which tends to be concrete, and to try teaching managers concrete thinking as well as abstract thinking.

A kanban system, for instance, is a way to represent information, by nature an abstract concept, in the concrete form of cards which can be manipulated and thus treated concretely. Without this understanding, most of the benefit of kanban disappears (for instance, digitalizing kanban doesn’t make much sense). Kanban is thinking about information as we think about concrete objects.

A kanban system, for instance, is a way to represent information, by nature an abstract concept, in the concrete form of cards which can be manipulated and thus treated concretely. Without this understanding, most of the benefit of kanban disappears (for instance, digitalizing kanban doesn’t make much sense). Kanban is thinking about information as we think about concrete objects.

Here we can see the materialization of precise pick-up times for kanban cards, which is making concrete the information flow.

Real Visual Management

PowerPoint graphs on the wall, although unavoidable, are not visualization – they are abstract thinking put on a wall. Charts on wall are an attempt by management to bring workers into the management sphere – to get workers to understand management’s problems. On the contrary, visual management is a way to bring managers to understand the worker’s world – and obstacles to solutions.

PowerPoint graphs on the wall, although unavoidable, are not visualization – they are abstract thinking put on a wall. Charts on wall are an attempt by management to bring workers into the management sphere – to get workers to understand management’s problems. On the contrary, visual management is a way to bring managers to understand the worker’s world – and obstacles to solutions.

Some boards are necessary to bridge the gap and discuss issues, but real visual management is the materialization of the difference between OK and not-OK, that will reveal problems to be solved by employees and frontline management.

Some boards are necessary to bridge the gap and discuss issues, but real visual management is the materialization of the difference between OK and not-OK, that will reveal problems to be solved by employees and frontline management.

These techniques are not taught in any of the books I know, nor is their critical importance well explained. After all, books are about abstracting “lean” from concrete TPS practice. This is why learning with a true sensei, steeped in the Toyota tradition makes such a difference to understanding lean thinking, or, if you don’t have access to a sensei, looking specifically for examples of Toyota’s visual practices with “materialization” in mind.

One executive scoffed at the reaction of Toyota’s president to one crisis or other when he said “We will continue to make cars one by one.” “Obviously, they make cars one by one,” the exec laughed “how else do they expect to make them?” True, the assembly line assembles cars one by one and it’s hard to imagine them by the dozen, but the exec was missing the fundamental point of “one by one.” One by one in lean thinking means thinking concretely of every car as an individual object, worthy of all our attention, and concretely solving the minute problems this car will experience from its life on the production line – not thinking abstractly about producing cars. This is like taking care of one specific patient rather than curing as disease as a whole.

One executive scoffed at the reaction of Toyota’s president to one crisis or other when he said “We will continue to make cars one by one.” “Obviously, they make cars one by one,” the exec laughed “how else do they expect to make them?” True, the assembly line assembles cars one by one and it’s hard to imagine them by the dozen, but the exec was missing the fundamental point of “one by one.” One by one in lean thinking means thinking concretely of every car as an individual object, worthy of all our attention, and concretely solving the minute problems this car will experience from its life on the production line – not thinking abstractly about producing cars. This is like taking care of one specific patient rather than curing as disease as a whole.

Clearly, abstract reasoning is very powerful and the key to solving large problems. But concrete reasoning is just as powerful to understand the details of doing the job well, where performance truly lies. In the end, real insights are born from practicing both.