As you prepare your organization’s at least partial return to the office, I urge you to take the time to reflect on what you’ve learned about the work. Treat the four months since the Covid-19 pandemic sent millions of workers in various occupations to shelter and work at home as an experiment. The slice of the workforce that was able to move their work to home—estimated to be somewhat more than a third of all workers—includes the group known as knowledge workers. Knowledge work, loosely defined as that which requires solving non-routine problems at least part of the time, is generally the least examined of all work, at least with respect to process. Thus, reflecting on your work-from-home experience promises to provide needed insights about knowledge work and the routine work that accompanies it—both the work itself and its underlying processes.

Over the last few weeks, I have had numerous conversations with managers and executives charged with managing groups in various industries that moved from office to home. The purpose of the discussions was to reflect on what we have learned about the work itself. I spoke with leaders of software development, auditing, internal consulting, research, underwriting, legal, and other businesses. In all cases, we considered processes that included some combination of incidental work and value-adding work.

Based on those conversations, I offer some observations about what the move from office to home tells us about the work itself. I conclude with a guide to help you reflect on what the switch from office work to homework reveals about the underlying processes in your organization.

OBSERVATIONS

Adapting the Home for Work. Although leaders complained about the difficulties of adapting home technology to real work, I continue to find it truly amazing that IT infrastructure was robust enough to facilitate the move to home almost overnight. Leaders generally reported that IT groups were usually quick to help—from a distance—to improve situations that did work well enough.

It was abundantly clear based on my observations that the more steeped the organization is in lean thinking and practice, the easier the transition to work-from-home. In particular, those organizations that commonly applied standardized work to routine processes made the transition relatively easily, particularly with respect to consistency. Similarly, those with existing daily management systems, including adherence to visual controls, standard work for leaders, and daily accountability, fared better in managing the transition than those who did not have such systems.

Maintaining—and Measuring Productivity. In general, findings from my conversations mirrored press reports from company leaders that productivity of processes that have moved home is as good as before the move, at least at first blush. However, leaders confessed some skepticism about the happy assessment for several reasons, including:

- concern about burnout because employees seemed to have issues with work versus non-work time boundaries, further complicated by childcare and numerous distractions. They questioned whether the pace would continue.

- a belief that the novelty of work-from-home would wear off, causing productivity measures to drift.

- suggestions that what was measured was somewhat deceptive, based on doubts that routine work, comprising much of the time consumed, can be standardized and progress measured quite easily. The non-routine knowledge work remains challenging to measure in time and quality, but this problem exists regardless of the locus of the work. The trick seems to be to discover ways to align incidental processes to better support the qualitatively more important knowledge work so that it can be accomplished with more reliable results in time and quality.

It is worth noting that some executives revealed accelerated plans to incorporate automated productivity management systems into processes. Of course, these systems focus on routine work rather than the more mysterious—and implicitly more valuable—knowledge work that involves the non-routine.

Understanding the Whole. Work that can be done from home is generally bounded by the automated workflow created to complete it. People generally understand that flow, which serves them well day-to-day. However, surprisingly little understanding exists of the work that lies outside the boundaries of the workflow—even work in the same value stream.

As lean thinkers, we have long agreed on the importance of seeing the entire value stream and understanding how it accommodates customer needs. Problem-solving that is constrained to the workflow will inevitably lead to solutions that may be optimal for the workflow but not for the entire value stream. Worse, too often, this problem-solving requires the use of “experts” who do not have daily workflow responsibilities to address value stream problems. This approach causes delays and risks overlooking the expertise of the people who do the work.

It is not surprising that this “value stream myopia” exists because work-from-home is almost always mediated by computer systems and, almost inevitably, defined workflows. It is surprising to me that the issue exists even in organizations that are, in many other ways, reasonably accomplished lean practitioners.

Ensuring Job Satisfaction and Company Culture. Those of us who can work from home are generally privileged in the sense that we have jobs at all in a challenging economy. Evidence revealed by the press suggests that people who are working from home mostly enjoy it. My conversations are consistent with those reports—in fact, a couple of leaders indicated that recent satisfaction surveys showed that overall job satisfaction was up measurably.

However, it was clear from my conversations that Zoom only goes so far. People miss face-to-face interactions with their colleagues. Also noted, was that serendipity plays a role, particularly with problem-solving and innovation. Unplanned meetings at the coffee bar with those who are outside of the workgroup no longer happen. Research shows that barriers to interaction tend to stifle innovation. How will those unplanned, coincidental meetings be replaced?

Perhaps the more significant issue is culture—an item that successful companies have spent considerable effort getting right and instilled. A likely long-term outcome of the work-from-home experiment is that most people will continue to spend some significant part of their time working from home. Such a change can yield net benefits to individuals in terms of lifestyle, to employers in real estate savings, and to the environment. However, harvesting those benefits cannot come at the expense of maintaining a lean culture. So much of building and sustaining lean culture depends upon positive, gemba-based interactions. Leaders will need to rethink how, when, and where such communications will take place.

A Guide for Next Steps

I have argued that moving the work from the office to home can help you better understand the work itself and the processes that underlie that work. My argument is not that the locale’s change is itself of lasting importance but that the switch provides an opportunity to look with fresh eyes at what seems to work well and what doesn’t. I offer the following as a guide that may be useful in this reflection. As always, observation should be at the gemba, where, in this case, the gemba is mostly virtual.

Gauging the Use of Essential Front-line Tools

Two fundamental tools in lean are standardized work and visual management, and many organizations use both for improving “office work.” However, my observation is that the real use of these tools is often mixed. In some instances, they are used daily and with good effect. In others, they are more ornamental (to please the boss) than useful. The move to work-from-home can provide insights into where an organization falls on the useful-versus-ornamental divide.

Standardized work is useful because it can change to reflect learning as it occurs, and as circumstances are modified. I have observed no cases where standardized work should have remained unchanged as work moved from office to home. Have you made changes to your standardized work? If not, it suggests that it is, at best, an historical document or, at worst, an ornament.

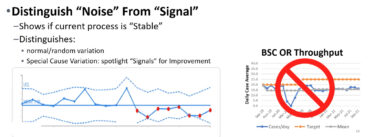

Visual management is frequently seen in offices in the form of charts on the wall that track the progress of work, provide a visual record of assignments and due dates, and indicate when future work should begin. Have you made efforts to replicate these charts to make them useful by those who are now working from home? If not, the group is being managed without visual management, suggesting that the wall charts back at the office were mostly decorative.

Assess Your Systems. The move from office to home also provides an opportunity to determine whether your systems are working effectively. Though your organization’s systems are unique to its architecture, I find it useful to evaluate them based on four interrelated domains of operational governance that are always necessary. These include the problem-solving system, the daily management system, the strategic management system, and the people development system. You can substitute a different model, but the idea is to think at a high level about what the move from office to home reveals about how the organization operates.

Review Your Problem-Solving Systems. An organized approach to solving problems is fundamental to continuous improvement. What are the ways that your organization systematically surfaces issues, understands their cause, and develops countermeasures as experiments? How are problems escalated? Has there been a change in behavior since the move home? For example, has there been a change in the number of A3s generated or completed? Evidence of such changes in practice suggests that your problem-solving activities are not operating as a system to the degree they need to be.

Check Your Strategic Management Systems. Moving work from the office to home is an extreme decentralization of operations that may reveal cracks in the operational strategic planning system. Are you paying a price in terms of alignment among units and with the marketplace? With regard to planning, is the discipline of catch-ball still working the way you expect it to work? Does everyone understand the strategic intent of the organization? If the answer is no to these or similar questions, you must adjust your systems to accommodate a more meaningful flow of information.

Evaluate Your Daily Management Systems. Daily management is a tiered system that uses visual management and short meetings to establish a cadence of leaders’ checking on progress and accountability and to communicate issues up and down the organizational hierarchy. Effectively, it provides regular readings of the current status of the organization’s work. The cadence was almost inevitably interrupted as the need for virtual meetings and redesigned visuals replaced in-person meetings and physical visuals. However, you can make adjustments quickly if the system itself is otherwise working well. To what extent has the flow of important information about the status of work been interrupted? How well do managers seem to have their finger on the pulse of their operation? Has there been a degradation of the ability to inform all who are affected by problems as they occur? Knowing less about the status of work in the organization is cause for concern and suggests that daily management is not working as it should.

Update Your People-Development Systems. The need to help people grow in their job is always urgent and is central to lean thinking and practice. Discussions with my sample of leaders indicate that people’s development has been on the back burner for numerous reasons, including restricted travel and the need to focus on the day during a challenging economic period. However, as the months pass, you need to bring on new people, upgrade skills, and continue coaching. You might ask the extent to which work-from-home has upset planned development activities and what you might do to ensure that the inevitable future disruptions have fewer implications for people’s development. Perhaps more important is the issue of coaching, which has been a key approach for developing people in lean organizations. Because the likelihood is that some fraction of work will continue to occur outside of the office in the future, your organization must build skills in virtual coaching. More generally, leaders might ask about the quality of coaching that occurs currently and how those skills might be improved.

Gaining Wisdom Through Experience and Reflection.

Most leaders are very busy planning phased (at least partial) moves back to the office while also thinking through contingencies in a very uncertain environment. Pandemic disease, social upheaval, and economic crises have converged to make for long days and difficult decisions for organizational leaders.

Most leaders have already experienced significant upheaval in shifting to work-from-home for their organizations. There is a tendency to view that shift through the rear-view mirror as there are new challenges to face. I ask that each of you who have led the move of work from the office to home to mark out some time for reflection on what the experience can teach you about the underlying work. I also ask that you reflect on how those insights can, in turn, help to reveal the strengths and weaknesses of your organizations’ underlying organizational systems.

I would love to hear your thoughts.

Sincerely,

Peter

Chairman, Lean Enterprise Institute

P.S. For the latest online education in lean thinking and practice, check out the Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX), an immersive 10-week course of study that will develop your and your team’s in-depth understanding of lean thinking and practice. Hosted by the nonprofit Lean Enterprise Institute, the VLX begins September 14.