To close each week of the Lean Enterprise Institute’s Virtual Lean Learning Experience 2020 (VLX), we bring together the week’s speakers for a Q&A and discussion on Zoom. The panel ending the Kickoff Week covered a wide range of topics, including the following: a review of how Toyota is responding to issues arising from the pandemic, how company leaders are “going to the gemba” and continuing Obeya meetings virtually; what industries are most in need of lean thinking; how can young professionals best find ways to apply the lean concepts they learned in school in the more difficult, real-life situations, and more. Here’s an excerpt:

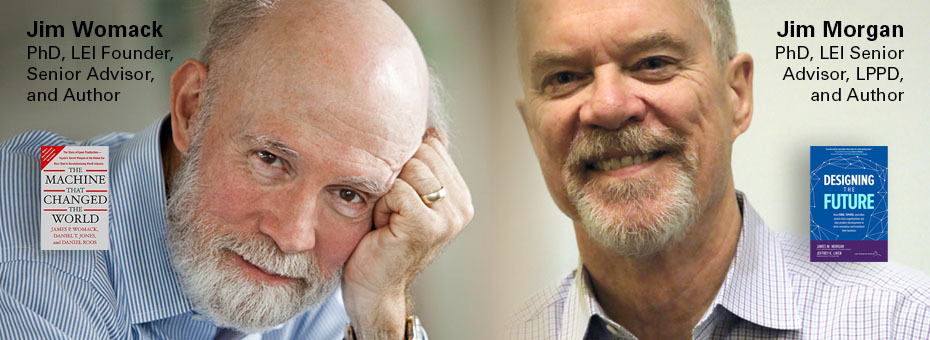

Josh Howell: Welcome back to the Virtual Lean Learning Experience, the VLX. Today, we are here for a panel discussion with our speakers from Tuesday, LEI’s founder and board member Jim Womack and LEI senior advisor and, recently, COO of Rivian Jim Morgan. I am Josh Howell. I’ll be hosting, moderating the discussion today. I am the president of the Lean Enterprise Institute.

So getting started is one thing, in whatever industry you might be in. Many of us are working for organizations that have gotten started, and that might be struggling with their lean transformation. So there have been a number of questions coming in related to that, around the challenge of transformation and what we have learned about that process over the years and what we can do better or differently going forward.

Now underway, Designing the Future, the final track of The Virtual Lean Learning Experience 2020 (VLX), is a two-week immersion into Lean Product and Process Development. The presentations feature advanced practitioners sharing learned drives success.

Jim Morgan, one question that came in for you was a question around if you could give an example of a successful, lean product and process development implementation and maybe an example of one that was not so successful, and what you learn from the differences in those two experiences. Of course, you work for you; you work as a senior advisor for the Lean Enterprise Institute. You don’t work for organizations that are tackling these things day in and day out today. So you may be limited with what you can share. Certainly, you’ve learned some things over the years, and there’s interest in gleaning your know-how around that topic.

Jim Morgan: Yeah. Gosh, we probably could have started with that question and spent a whole hour on it. And you’re right. I can’t talk about, you know, specific programs or companies–that would be completely inappropriate.

But I do think that starting with a real need is crucially important. If it doesn’t matter to the business, it’s hard to get the resources and the attention and the focus, I guess, that is required. Also, I think that a willingness to pivot, to use a term I’m not particularly fond of, but the willingness to just burn it down, blow it up, and start all over is incredibly important. When we talk about implementing lean principles and practices with a sense of urgency with the business that was starting to get up and running, it was extremely important not to just continue to chase something that was clearly not working and be willing to just sort of start over again.

So, I think those are all important: Helping the business fundamentals. Being willing to try the experiment and pivot when it doesn’t work. Engaging people just in time with training [so you don’t] outrun your learning as you’re starting to implement this stuff. Finding programs to pilot, so it’s part of the real world. Not spending a bunch of time on jargon and dogma, and we must do this, and we must do that. Thinking from first principles and then reasoning from first principles, I think these are all elements or characteristics of successful implementation and successful programs.

Also, creating a situation, whether it’s the product itself or the implementation of the system where it becomes aspirational. During my time at Ford, when [Alan] Mulally was there, inspiration was such a big part of what we were doing and what we wanted to be part of. During my time at Rivian, many of the people there are there because they really believe in what Rivian stands for and what they’re trying to accomplish. Being inclusive and enrolling people in that is also hugely important.

In terms of the downside, there are lots of things that I could cite. Not doing enough up-front in the study period; not really understanding your customer and context, whether it’s for a program or implementation; not having a clear view of what “good” looks like and what problem we’re trying to solve; not engaging all the right people and trying to do it sort of in a, in a small pocket.

But the biggest disasters that I’ve seen in terms of programs is when you skip steps. When you say we’re going to shorten our lead time by eliminating this or this, right, because we don’t need it anymore. We don’t need to build physical prototypes. We don’t need to have production tryout builds. We don’t need whatever, and you eliminate them without a countermeasure. You eliminate them without an enabler. Those are the programs that I think struggled the most.

Womack: Can I just say one word about that?

Howell: Please.

Womack: I’ve been doing this for a long time, and what I find that is an important enabler of success is that there’s an actual engagement between the improvement folks and the line management. We came into this in a sort of a bad way, back in, say 1990, when everybody was in a big hurry to do lean, and people set up lean teams that were inspired by the OMCD [Operations Management Consulting Division] folks at Toyota, who would basically do lean to people. They would show up and say, okay, this week, we will move all the machines. We’ve done a quick assessment. We know we’ll be better off to get out of process villages and product family value streams. We brought our pry bars and all kinds of other equipment, and we’re going to do it.

And I watched a gazillion of those way back when, and the problem was that almost none of it could be sustained at the level that was achieved at the end of the improvement cycle, because, in fact, the line management had no experience in how to run a stable process. They themselves had no knowledge of how you improve. And so an unfortunate dependency relationship came up that the line folks, anytime something either went wrong or someone said, you need to improve said, “I believe I’ll outsource that to the improvement team.”

And, hey, the improvement team is happy to get started. Great, more work! But, downstream, this may not lead anywhere because there is no real engagement, and there’s no development of managers. So Toyota some years ago, changed the name OMCD to OMDD, which is the Operations Management Development Division. They now see their job as developing line managers who can do the things that they used to do. So they now become coaches, enablers, educators, rather than do-it people. And that for them has been a formula that’s worked well. You don’t see that so much elsewhere. So I think there’s a lot of opportunity for experimentation there.

Morgan: That actually reminds me of another failure mode that I didn’t mention that I should, and that’s organizations that try to transplant directly what they were doing in the factory into the product development system, without really understanding the unique nature of that environment. You turn off engineers and developers and designers really quick when you show up and decide the best thing you can do is, you know, draw a circle around their wastebasket or something. So, really understanding the environment and the challenges is critically important as well.

Howell: So, with that, it is a wrap. Thank you, Jim. Thank you, Jim. Thank you to everyone who joined us today. Thank you to everyone who will watch the replay of this video at a later time. We will see you online and remotely through Zoom, just like everyone else in our lives these days. All right, bye for now. Thanks all!