Dear Gemba Coach,

I keep hearing that a tool approach to lean is wrong, but tools deliver results – how can that be wrong?

There’s nothing wrong with tools – the debate is how the tools are used. This debate ranges from humble 5S to lofty hoshin kanri. The deeper question is your theory about “results.” Are you:

- Using the tools to force people into doing something to make the situation better and have quick visible results?

Or:

- Teaching the tools so people understand better their own work, develop their initiative, and encourage them to better understand abnormalities, better interpret what is going on, and react more smartly?

I was last week on the gemba in a traditional service company that is working hard at embracing digital change. The leaders debated the hoshin plan about digitalization, one of the smartest young executives of the company demonstrated the first version of a smartphone app, all well – and impressive for such a traditional company. They’re moving along, and they’re doing so by encouraging new talent and new thinking.

Then we walked down to the warehouse… which was a complete mess. Well, mess is not the right term. It would have looked good on photos as it was tidy, but when you looked in details, heavy dangerous parts were stored high up, boxes were mixed up, there was no visual sense of lead-time. It was just tidy.

The age-old debate in that place is that the logistics manager understands 5S as a way to keep his warehouse ordered – and senior management stays out of it. So, he tells his guys what to put where and chases after them regularly with clean up time-outs and so on. But of course, in the day-to-day of work since the team doesn’t understand the purpose of the 5S, unused parts accumulate in corners, old stuff stacks up and so on.

The logistics manager has his quick visible results – but they’re never sustainable and, truth be told, after the initial gain have been achieved (the very first 5S drive did reduce surfaces spectacularly), there hasn’t been much performance improvement.

This is a strategic issue because as part of the hoshin plan, this company intends to become the “Amazon” of spare parts in the industry. The goal is that competitors should order their own parts with them because it is easier so that they become the first search point for the entire industry. This is a clever strategy… which requires Amazon level warehousing – without amazon level access to capital and investment.

5S is not a tool to have a cleaner shop floor. It’s a tool to develop practical decision making in all employees every day:

- Sort: Learn to separate useful stuff from unneeded tools, parts, paperwork, and remove what you don’t need right away. This sounds silly, but in actual fact is a tough decision because who knows whether you won’t need tomorrow something you’ve discarded right away. It requires thinking about what you use, having some sort of keep/replace strategy. It’s tough.

- Straighten: Organize objects and paper in a way that makes standardized work easy. Again, this is far from immediate. It requires a strategy, such as where do we put items that we use more frequently, those that we use occasionally, handy stuff, cumbersome stuff, and so on. The test of “straighten” is that you can find something you’re looking for with your eyes closed. This also means creating visible places for everything and changing that as flow changes. It’s tough.

- Shine: Make sure that everything you hold in your work environment works well at first touch – this links to the jidoka issue of “separating machine work from human work.” Basically, when you want to use something, can you do the work at one touch, or do you need to fiddle and fight with it to get it to work – by which time your cycle time is shot to hell, quality suffers, and you get really annoyed. Shining is quite complex since we can’t check everything every day. It requires some kind of a plan to test items and fix or replace what doesn’t work at first touch, rather than do what we all do, which is wait for things to fall apart before we look into them. It’s tough.

- Standardize: This means building the three previous “Ss” into your daily work routine. Again, it’s tough. There are not enough hours in the day just to get the job done and we need to set some aside to clean up? Well, we do brush our teeth every day … Standardizing involves understanding the “finishing touch” to every job to make sure that it goes good to the next step, and setting the work area back in standard condition before starting the next job. In a café, it’s clearing the table and wiping them just after a person has left rather than leave all messy tables to be cleaned up at once (and often sitting people at tables that then need to be cleared up and cleaned in a hurry). Standardizing is the true reflection of how well we understand the job.

- Sustain: This fifth “S” doesn’t exist at Toyota (who talks about 4S) but became necessary at suppliers – it’s about management keeping up the discipline of the four previous Ss. Here also, it’s not about management asking for a “neat” workplace. It’s about asking pointed questions about how the organization of the workplace sustains the flow of work, and whether the commitment to practices is maintained and, most importantly, what can be done to help?

5S can, therefore, be used either as a way to beat people into having a tidy-ish workplace by forcing them to sort, straighten, shine, and so on. Or it can be used as a self-study and self-development tool to get people to observe their own working practice (why, exactly, do I keep two piles of papers on my desk?) and act by making small – but nevertheless difficult – choices daily. And, in doing so, understand more deeply how they work and how they could work better.

I love studying lean, I truly do, because when done right it is the only management method I know that allows for true self-development. Back in the early XIXth century when industry was discovering Taylor’s methods of setting processes by engineers for operators to follow to the letter without thinking or asking questions, Sakichi Toyoda was reading Samuel Smiles’ Self-Help book (literally, the first book of the self-help literature) that praised initiative and showed how gifted individuals lifted themselves from their conditions by pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps by … learning (Toyoda’s copy is still on display at the Toyota museum).

Yes, the tools are powerful. They can be used for compliance, and indeed have quick, visible results that will never be sustainable or offer a way to go beyond the low-hanging fruit (try to get out of that dead-end though, when you’ve gone down that route!). Or they can be used to develop initiative and judgment so that people, understanding deeper aspects of their work, learn to bring smarts and care to everything else they do in the job – from welcoming a customer, to tackling a tricky task, to surrounding themselves with the right co-workers and so on.

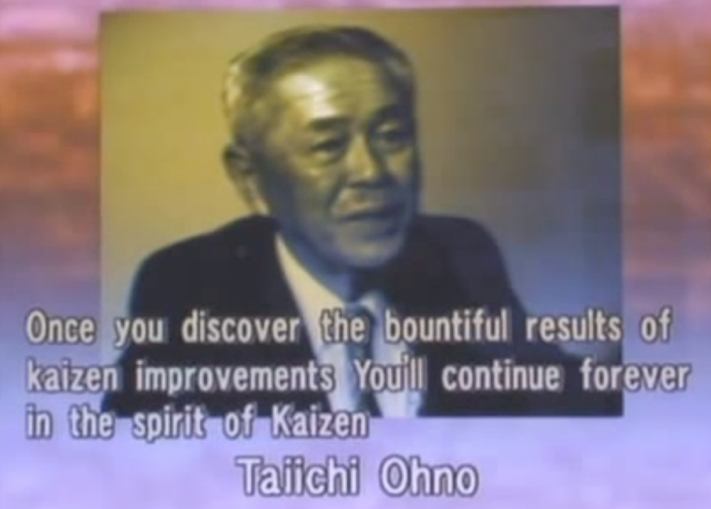

Without the tools, such as 5S, kanban or kaizen, there can be no self-study or learning. But applying the tools as “best practices” to be forced on people doesn’t do much either beyond early apparent results (which is all many managers ask for, sadly). However, using the tools to develop initiative daily and encourage self-development, increases the flow of ideas and delivers an endless stream of continuous practical improvement that builds up into competitive performance. As Ohno is quoted saying: “Once you discover the bountiful results of kaizen improvements, you will continue forever in the spirit of kaizen.” But to understand kaizen with a small “k” you also need to grasp kaizen with a capital K: progress through process improvement, through people self-improvement.