“Just challenging the simple notion of top down control is still an uphill struggle,” says Dan Jones, Chairman of the Lean Enterprise Academy in the UK. “It is simply not what managers want to hear.” Advocates of advanced management and production methods have been able to “get management’s attention and challenge batch thinking to a degree,” he says. But there’s still much more to be done.

Advocates of reform argue properly that top-down control of the movement of work-in-process and inventory only creates chaos in production. Production and supply managers react to production breakdowns by increasing batch sizes and lead times. But, as I’ll explain, Denis Towill’s “FORRIDGE” theory shows how these intended remedies actually lengthen queues of batches, which in turn make production exponentially more chaotic.

We know just-in-time (JIT) flow of defect-free parts is essential for successful implementation of Lean. Quick feedback loops in each step of the flow of inventory end up replacing the production control department. Batch sizes shrink. Queues disappear. Quality becomes manageable. And production runs more smoothly.

Replacement of batch and queue logistics with JIT flow also lays the groundwork for even higher levels of enterprise productivity and job satisfaction. Indeed, production systems are coming online based on a new design that gives workers real control of production operations and manufacturing processes. More than any other, this new system of work uses the most valuable asset of any enterprise—the minds of its workers—to lead production and make process improvements to increase productivity. It’s called Worker Leadership, and it’s based on ancient wisdom: the bigger the opportunity to be productive, the more satisfaction we get from our work. Or, as workers put it, “The more I love my job.”

The true cost of batch and queue methods of managing production then is the loss of gains to be had from lean manufacturing (which depends on JIT), plus the loss of the additional profits and job satisfaction from Worker Leadership (which builds on lean manufacturing). It’s a steep price measured in lost market share.

To decisively dispel any lingering beliefs that more inventory and longer lead times will deliver the economies of scale we seek, let’s take a deeper look at Towill’s remarkable theory. It explains why batch and queue systems are incorrigible and why JIT is inevitably superior.

The Gift of Batch and Queue

In 1804, Eli Terry, a Yankee clockmaker in Connecticut, invented mass production and cut the costs of producing clocks by a factor of ten. Mass production achieves its economies of scale by separating fabrication of parts from their assembly. Factory managers install precision machines to fabricate interchangeable parts. Once a machine is set up, processing parts in batches of hundreds or thousands reduces unit costs to pennies or less. Assembly is also much cheaper. With precision interchangeability, quick assembly by lower-skill workers displaces slow, laborious file-to-fit assembly by expensive craftsmen.

By the beginning of the 20th century, “big batch” mass production dominated American manufacturing. In mass production, managers organize fabrication of parts into functional departments of similar machines through which batches make their way from supplier delivery docks to assembly departments. To keep costly machines busy, production control departments keep queues at each functional department loaded with batches of parts awaiting processing. By the mid 20th century, the American batch and queue model of mass production was a global standard. Unfortunately, it remains widely popular today.

The problem with batch and queue factories was, and still is, this: they create expensive production problems. No matter how many warehouses bulge with inventory, how many production control clerks are busy planning production, how many parts expediters are searching for needed parts, or how much horsepower the manager who chairs the daily 6:30 AM parts shortage meetings has—production at batch and queue factories always seems held up by parts shortages. And despite our long experience with the practice, we didn’t fully understood what was going on under the hood of batch and queue inventory flow, that is, not until mid-century.

Dirty Secrets of Batch and Queue

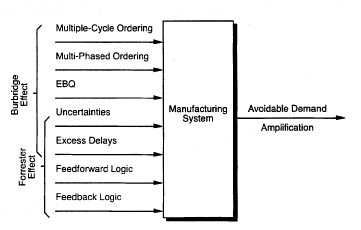

Finally, in the 1950s, some clues began to emerge. And then in 1961, Jay Forrester and Jack Burbidge separately published research addressing different aspects of the persistent inability of batch and queue systems to deliver part when needed. Their articles appeared in Industrial Dynamics and Production Engineer respectively. It wasn’t, however, until 1997 that Towill, Director of the Logistics Systems Dynamic Group at Cardiff University Business School, combined the two research efforts into a unified theory (“FORRIDGE” from Forrester+Burbidge) explaining how batch and queue breaks down in practice.

In a revolutionary paper that has received too little attention, “FORRIDGE – Principles of Good Practice in Material Flow,” published in 1997 Production Planning & Control, Towill shows how management of functional shop departments as independent businesses creates complex and counterintuitive failures of batch and queue operations.

Why? One culprit is queuing of batches. The fundamental phenomenon is that nets of feedback loops, both known and undetected in manufacturing inventory and job control systems, create an “inventory chain which suddenly, and without warning, switches from acceptable to unacceptable service levels… causing system chaos and breakdown.” This is known as the Forrester effect.

Why? One culprit is queuing of batches. The fundamental phenomenon is that nets of feedback loops, both known and undetected in manufacturing inventory and job control systems, create an “inventory chain which suddenly, and without warning, switches from acceptable to unacceptable service levels… causing system chaos and breakdown.” This is known as the Forrester effect.

Then there’s the Burbidge effect. Burbidge shows that dynamic interactions of batches queuing through shared processes, like production departments, cause unpredictable surges in material usage and what appear to be random increases in throughput times. In an article by Towill and his colleagues Steve Geary and Paul Childerhouse, “Uncertainty and the Seamless Supply Chain” in Supply Chain Management Review, we learn that when the stock control systems treats each component within a product separately, the result is “extremely variable multi-cycle, multi-phase flow leading to highly fluctuating inventories and stop–go plant utilization. These systems often lead to the mistaken belief that the first step in improving customer service is to increase inventory levels.”

Uncertainties from Burbidge effects layer on top of Forrester effects, unavoidably resulting in random chaos and breakdown. Towill shows that the likelihood of flipping into chaotic conditions increases exponentially with complexity of material flow. To cement the counterintuitive character of the calamity, second-guessing and just-in-case behavior among planners, production managers, and supply managers only makes things worse. Longer lead times don’t help. Towill observes, “The longer the lead time, the greater the problems arising from system instabilities . . .” Batch and queue may have worked well for Terry and others in the 19th century (making one product with a relatively simple flow among fabrication operations), but it doesn’t work in modern factories making complex products. And the theory warns us: the harder you try to fix it, the worse it gets.

Remedies for Batch and Queue

Burbidge recommends a flow control system he called “Period Batch Control.” It is a “just-in-time system, designed to assemble products when they are needed to meet customer orders: to make parts when they are needed for assembly; and to accept delivery of bought parts and materials only when they are needed for further processing.” In 1983, he codified Period Batch Control into “Five Rules for Avoiding Bankruptcy:” which Towill lays out for us:

RULE 1: Only make those products which you can quickly dispatch and invoice to customers.

RULE 2: Only make in one period those components you need for assembly in the next period.

RULE 3: Minimize the material throughput time.

RULE 4: Use the shortest planning period, i.e. the smallest run quantity which can be managed efficiently.

RULE 5: Only take deliveries from suppliers in small batches as and when needed for processing or assembly.

It’s unfortunate that the concepts of just-in-time flow of material and work-in-process formulated by Forrester and Burbidge went largely unnoticed until James Womack, Dan Jones, and Dan Roos frightened Western manufacturers with the truth about Japanese production systems. Towill sees the problem of motivation this way:

“Unfortunately reading is not recognizing, and hoping is not doing, and relying upon is not reinforcing. Furthermore all of these processes are time-consuming and subject to ‘noise’. So it is not altogether surprising that good practice frequently went unrecognized, until, that is, our competitor beats us on quality, lead time, service level, and total costs simultaneously. We are then in grave danger of going out of business.”

The Exciting Future of Work

Now we can see why batch and queue is inevitably costly compared to Toyota-style systems. For more insights into the problems batch thinking presents for Lean, please see Ian Glenday’s recent Lean Post “The Problem With Batch Logic.” Worse yet, the opportunity costs are higher than just the loss of potential gains from lean manufacturing. With batch and queue, worker teams cannot manage production even if motivated and empowered. The information needed for workers to control production and solve problems is scattered through a factory swamped with inventory. The worker’s world, in contrast, is a couple of machines and the batches of parts queued for processing. But with Worker Leadership, built on a foundation of lean manufacturing, workers can take charge of production and deliver the dramatic improvements in enterprise productivity and job satisfaction promised by the ancient wisdom of, “A productive worker is a happy worker.”