“What’s needed instead is system kaizen in which the material-handling system for an entire facility, supplying every value stream, is redesigned to create a bulletproof delivery process that is utterly precise and stable … Such a system must include a plan for every part (PFEP) that documents all relevant information about each part number in the facility, including its storage location and points of use.”

-Jim Womack, (Gemba Walks, 2nd Edition, 2013, p. 28.)

With so many essential aspects to address and implement to achieve a successful lean transformation, it’s no wonder many organizations overlook a key piece of any lean material handling system: a plan for every part. “In most facilities I visit, the material handling system is a mess,” Womack writes in Gemba Walks. “If there is a pull system in place, it is run very loosely, with the same part number stored in many locations …”

In fact, some lean practitioners have noticed a relative lack of a lean material-handling system at many companies that have undertaken a lean transformation. “As I walk through facilities and examine earnest efforts to create continuous flow, I see how hard it is to sustain steady output,” says Rick Harris, co-author with his son, Chris Harris, and Earl Wilson of the Making Materials Flow workbook, which won a Shingo Research Award. “The problem often is the lack of a lean material-handling system for purchased parts to support continuous flow cells, small-batch processing, and traditional assembly lines.”

Lean Material Handling Steps

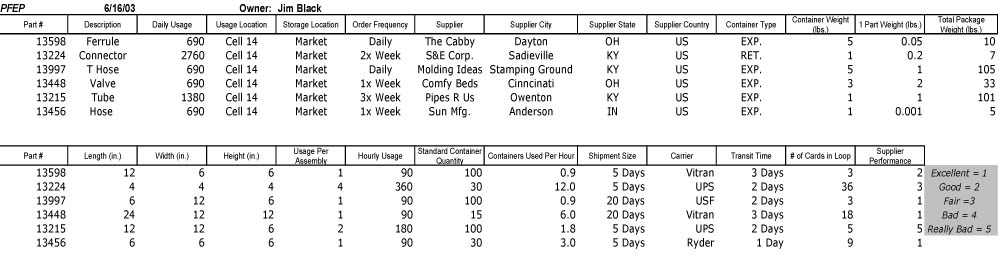

The first step in creating a lean material-handling system is to develop a Plan for Every Part (PFEP). Essentially an electronic spreadsheet or database, the PFEP fosters precise, accurate, and controlled inventory reduction, while serving as the foundation for the continuous improvement of a plant’s material-handling system. It contains all the critical information about parts. This information, in turn, can be used to manage the material-handling system, size markets and storage racks containing purchased parts, and design timed delivery routes and kanbans.

“We view PFEP as the DNA of your plant,” says Rick Harris, president of Harris Lean Systems Inc. in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, which helped guide more than 40 companies around the world with their lean transformations. “Some companies have their part information spread in many different systems, but our view is that it should be all in one database. A PFEP is absolutely critical to a lean transformation.”

We view PFEP as the DNA of your plant.

Adds Chris Harris, “The problem is that companies typically store the information in many different places. Having a PFEP really makes you invest in your materials and parts handling to a level of detail not done before.

And that investment in time and effort can pay off. Rick recalls working with a chemical company that, after completing a PFEP, was able to reduce its inventory of purchased parts by 52% “because most of the parts were ordered via MRP based on a forecast that either was wrong or had changed over time and the parts were no longer needed.”

MRP Drawback

Purchased parts typically are classed in six categories– runners (used all the time), repeaters (used regularly), and strangers (used sparingly for make to order products), and whether they are easy, medium, or difficult to run. “Having a PFEP helps you realize which category your parts fall into,” Rick Harris says. “If you can’t schedule effectively, then you can’t run your production efficiently.”

Unfortunately, many companies still try to manage their purchased parts inventory off their material requirements planning (MRP) system. An obvious drawback of this approach is that MRP fails to provide any data about the size or weight of the box containing the part or component. “This information is critically important to lean, because most companies are actually storing 50% air in their parts racks.”

The typical PFEP contains a wealth of data about each part that afford the company the total precision of information needed to manage material-handling effectively. Each part will contain the details in a spreadsheet or other database showing:

- part number;

- hourly usage;

- average daily usage;

- storage and usage location;

- shipment size;

- supplier location;

- box weight;

- part weight;

- box and part dimensions;

- number of parts needed;

- transport carrier;

- transit time, and more.

(Copyright, Making Materials Flow, Lean Enterprise Institute, 2003. All rights reserved.)

But what about manufacturers engaged in assembling complex products containing large numbers of purchased parts — can they reasonably be expected to set up and maintain a database of thousands of parts, each with this kind of granular information? The answer is, unequivocally, yes.

“You may have 24,000 SKUs (stock-keeping units), and it may take you five years to build the complete parts database,” says Rick Harris. “But typically, what we find is that most of a plant’s volume is made up of 20% of their total parts inventory. In general, we are looking for a 50% reduction in inventory as a result of implementing a PFEP.”

Nonetheless, it can appear to be a daunting task at best, gathering and compiling the data on hundreds or thousands of parts. “One way is to let a couple of college students do the data entry,” suggests Chris Harris, author of several books on various aspects of lean and a faculty member at the University of Indianapolis.

For instance, at two focused automotive parts plants, the company tackled the job of creating the database one manufacturing cell at a time. Then managers put together the purchased parts market, pull signals, and tugger routes for that area. The idea was to enable people to develop familiarity with the way the database and system worked before it was extended to additional areas in the plants.

In general, we are looking for a 50% reduction in inventory as a result of implementing a PFEP.

Some companies start out inputting parts data into an Excel spreadsheet, but they soon switch to a database application such as Microsoft Access. “You have to have every part number in there, because every part is stored somewhere in the plant,” Chris Harris adds. “Whether it’s a high- or low-dollar part, you’ve got to have both. We’ve seen plants shut down operations because they didn’t have a 50-cent part.”

Just the exercise of creating a detailed inventory of parts can help drive continuous improvement efforts. Rick Harris recently worked with an assembly operation that was able to reduce its days of inventory from 53 to 39 as a result of implementing a PFEP. “The PFEP was the main driver enabling the plant to achieve a 14% gain in productivity and a boost in on-time delivery from 87% to 93%,” he says. “The PFEP by itself is just a document– it’s what you do with it that determines where the gains come in.”

One reason the need for a PFEP often gets overlooked is that companies undertaking a lean transformation tend to focus on other key aspects of lean. “For most people, lean is all about labor,” Rick Harris explains. “Labor is easy to get at. Unfortunately, in the typical plant, the materials cost tends to be 50% to 80% of the operation’s total costs, versus just 7% to 17% for labor. But it’s a different part of the process to attack the material part of the plant.”

What’s more, it won’t do to have a single PFEP for a multi-plant operation. “Each PFEP has to have a plant of its own,” Chris Harris says.

Many organizations may have undergone a lean transformation, only to find that they still suffer operational problems due to inventory flubs. “People often ask me, ‘Rick, why does my plant look lean, but it’s not?’ And the reason usually is that they’re not using a PFEP.” Plants operating without a PFEP often tend to carry more inventory than needed, have more people than necessary, run out of parts, and have excessive storage needs.

Once companies have built and adopted a PFEP, there tends to be no going back to the old ways of materials handling. “There’s no way to go back to the old way because their entire material delivery system is built off their PFEP,” adds Rick Harris.

Kanban Connection

The PFEP must be closely monitored and updated. “Most companies will establish a PFEP person,” says Rick Harris. “Typically this is the highest ranking production control person in the plant. This is the only person who can make changes to any part number.” Typically, changes are initiated by engineering, manufacturing, or people responsible for parts storage or packaging. “We use a control change document generated by production control,” he adds.

PFEP plays a key role in any lean transformation, Rick Harris asserts. “It’s instrumental in achieving your business objectives,” he says. “You can use it to calculate your finished goods inventory, parts routes in the plant, and shipping and receiving windows.” Many companies depend on the PFEP as the data source for printing kanban cards for specific part numbers.

“The PFEP is part of the bigger picture,” says Chris Harris. Adds Rick, “It accelerates the lean implementation process.”

Do you have a training course that is specific to PFEP

LEI offers a workbook that has an entire chapter dedicated the PFEP – its called, Making Makerials Flow: https://www.lean.org/store/workbooks/making-materials-flow/