It is human nature to see or hear about something we call a “problem” and think right past the situation to a solution. Jumping to conclusions causes us to miss critical information that we need to pinpoint the problem. When we assume that we know what’s going on with whatever we think is a problem situation, we often don’t “go see” what, specifically, is not working as it should.

Why does this matter? Not looking to precisely see what is not working as expected in a situation we are concerned about—be it process, procedure, policy, or system—reduces our chances of effectively changing the condition we want to eliminate. In a work situation, the conditions or events that we describe as problems — including missed deliveries and deadlines or information, rework, defects, errors, cost overruns, poor coordination, frustrated and resentful employees — result when something happens (or does not happen) when we’re doing the work. If we don’t stop to figure out what part of the operation is underperforming, we have little chance of changing the specific things that are creating the performance gap.

It is a simple fact: you can’t improve results until you identify and change what is not working as planned.

It is a simple fact: you can’t improve results until you identify and change what is not working as planned. Therefore, to address a work-related problem, you first have to recognize that what you are concerned about does not exist in isolation. That is what makes A3 thinking the ideal problem-solving method. The approach is a practical and powerful way to identify with precision the problem you must solve.

Understanding How to Approach A3 Problem–Solving

The first challenge in A3 problem–solving is to grasp the performance situation in which the unwanted condition exists, which usually means answering some key questions:

- How is what I am concerned about related to needed performance?

- Why does this issue in performance matter?

- What performance results are we currently getting in the situation?

- What performance results do we think we should be getting?

- What part of the work system is not performing as we expect?

Answering these questions depends on realizing that whatever we call a problem is part of a work process created to produce specific results that it cannot currently deliver, bringing us back to understanding the real problem.

What seems to you to be a problem may not necessarily be a problem the way A3 thinking defines a problem. And what is a problem to you may not seem to be a problem to others. Fortunately, if you can show something is a problem in A3 problem–solving thinking, there’s a good chance it will look like a problem to others in your company or operation.

In A3 problem–solving, a problem must meet two requirements to “qualify” as a problem:

- It must be an issue of performance in the workplace. The greatest concern for a business is the performance in delivering a product or service to a customer as planned. Continued operation as a business depends on achieving the intended results to survive and thrive. A problem needing attention is one that indicates that it is not happening in some way.

- It must be defined as a clear gap (ideally measurable) between a specific work condition or event and an agreed–to performance expectation or goal. These established expectations are usually described in the form of a standard, specification, procedure, process, target, policy, or system. Demonstrating that a performance problem exists depends on bringing a precise picture of what is or is not happening into comparison with an accepted description (ideally documented) for what should be happening in the situation.

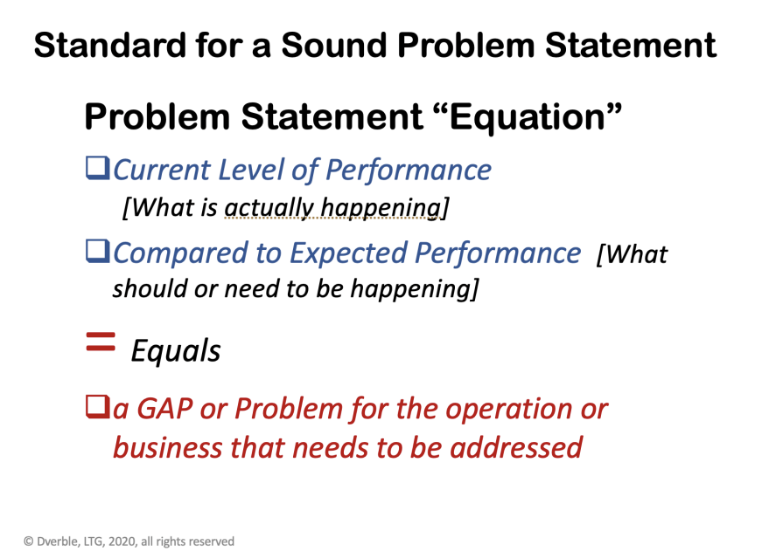

Sounds relatively easy, but in my 30 years of experience, the hardest part of the problem–solving process is saying precisely (ideally visually) what problem you are trying to solve. The challenge is to bring together the facts (and data!) to complete the problem statement “equation” – the current performance level compared to expected performance equals a gap or problem the operation or business needs to address.

Getting Clear

Let’s take a closer look at why we often struggle to meet the two requirements in the “standard” for an A3 problem statement. Why is it difficult to demonstrate in performance terms that a clear gap between what is happening and what should be happening exist in a work situation? Let’s look at an example showing how we often describe problems versus how they could be described (for easier problem-solving).

In touring a worksite once, I noticed a completed fishbone diagram with this problem description in the fish’s head: “Inaccurate Weekly Work Plans.” I assume everyone in the brainstorming session knew what that meant. The diagram listed at least a dozen causes, and the team had planned a similar number of corrective actions. But, with such a non-specific problem statement, the team was taking a shotgun approach to improvement and hoping that by shooting at every possibility, they would hit the real reasons that the work plans were inaccurate.

A PDCA/A3 problem–solving approach to that problem situation would be to ask, “Exactly what’s wrong about the work plans we are creating currently?” That would require asking, “What do we know about what needs to be in an accurate and complete work plan? And how is it supposed to be created?”

If you want to improve the work plans, you need to know how they are different from what they are supposed to be.

The answers to those questions bring us to the fundamentals of lean/A3 thinking. If you want to improve the work plans, you need to know how they are different from what they are supposed to be. Then you look at the process that produced the work plans and ask what is happening (or not happening) in how the process is being performed that created them. With some digging into the facts of what was happening (the “dirty details”), you might write a problem statement like the following:

I was not working with that team, so I don’t know what happened next. Still, I am confident that the team could learn what the exact discrepancies are. Seeing those errors and missing points led them to describe the problem as “Inaccurate Weekly Work Plans” in the first place. In A3 problem-solving, it is essential to know what those specific discrepancies from the standard are because you need to be able to track them back to the places in the process where the mistakes were made.

41% of weekly work plans created by Production Team 4 are repeatedly inaccurate or incomplete in 7 critical ways. Those 7 discrepancies from the standard for work plans are: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7…

This example demonstrates, ironically, one of the problems created by a poorly stated problem. The team likely created a lot of extra work (maybe even wasted work) for themselves because they did not start their problem–solving effort by clear stating what problem they needed to solve.

Why does it matter to share a problem in the form of a problem statement with the help of this clear problem statement “equation?” As so many of us already know, “A problem clearly stated is half solved.”

This Post was previously published on LinkedIn by the Lean Transformation Group, where David is a Partner, Performance Improvement Consultant, and Coach.

Managing to Learn with the A3 Process

Learn how to solve problems and develop problem solvers.