Dear Gemba Coach,

I have attended several lean conferences and am deeply interested in the topic, but puzzled about the diversity of viewpoints. Any advice on how to make up my own mind about what “lean” really is?

Thank you for this very interesting question. It is confusing – I remember the first time I was told I should not confuse the Toyota Production System (the system of interconnected activities to improve quality, cost, delivery, and lead-time) and Toyota’s System of Production (the system of Toyota’s present production practices). In similar mystifying fashion, I think we should be careful to distinguish lean thinking (a new way to think about business and the practical activities to learn this new way of thinking) and “lean” in general, which can mean anything from TPS to good ol’ fashioned cost cutting according to who employs the word. To your question: how can we orient ourselves in this jumble of ideas and practices?

The term “lean” appeared in The Machine That Changed the World as “lean production,” a description of Toyota’s superior approach to making cars, from designing the product to coordinating the supply chain, dealing with customers, organizing production from order to delivery, and managing the full enterprise. Lean production, in the book, describes Toyota’s practices of the 1980s and opposes these to previous craft and mass industrial approaches.

Authors Jim Womack and Dan Jones then wrote Lean Thinking six years later. Lean Thinking is a very different book as it describes how non-automotive companies responded to Toyota’s challenge. It tells of how pioneers such as Art Byrne and Pat Lancaster discovered the performance improvement potential of TPS, how they transformed their own businesses by learning with experienced ex-Toyota masters (senseis), and what general principles could be drawn from these early experiments, namely: (1) value, (2) value streams, (3) flow, (4) pull, and (5) perfection.

Lean Thinking remains as relevant now as it was 20 years ago, with the added understanding that the first four steps value, value streams, flow and pull are mostly about reaching just-in-time conditions and that TPS-type lean focused on takt time, standard work, and kaizen are wrapped up in “perfection.” In that sense, the book shows the prerequisite steps to lean and “lean” starts with step 5: pursuit of perfection.

To a large extent, these two books define the lean field (and explain why it can be so confusing): we have on the one hand a continued study of TPS and its evolutions at Toyota, both in terms of the learning system and Toyota’s current practices. On the other hand we have other company’s responses to Toyota’s challenge. For instance, back in 1994, Porsche was in dire straits and called in the veteran TPS consultants Chihiro Nakao and Yoshiki Iwata to help out, and the lean transformation recounted in Lean Thinking opened Porsche to larger thinking about modularization and work content, which then spilled over to Audi and Volkswagen. Two decades later, VW has toped Toyota as the world’s number one automaker, but Toyota generally is considered to be about twice as profitable as VW, and far more productive. In 2015, VW employs 600,000 people to produce 10 million cars while Toyota employs 340,000 to produce just under 9 million cars (https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/25/business/international/problems-at-volkswagen-start-in-the-boardroom.html).

Volkswagen’s latest scandal should not detract from the high overall quality of their cars, but certainly, reaching the top hasn’t happened without making some big gambles, both on markets and technologies, with, at this date, very uncertain outcomes. The Toyota/Volkswagen comparison illustrates well why it’s hard to get one’s bearing: is Toyota still lean and what is it doing to evolve TPS (Toyota’s New Global Architecture) and are Volkswagen’s efforts to compete with Toyota truly “lean”?

What Did Ohno Really Mean?

How, then, can we orient ourselves? Let’s start with figuring out what the inventors of the Toyota Production System had in mind in the first place. In this we are very fortunate because one of the key founders of TPS, Taiichi Ohno, has written three books detailing his thinking: Workplace Management, The Toyota Production System and Just-in-Time for Today and Tomorrow. These three books are an absolute MUST READ starting point.

Toyota’s context in Japan in the ‘50’s was so different from our own that it’s easy to dismiss much of what Ohno writes as archaic but, actually, this is exactly where the essence of true lean thinking lies. Do not focus on what you understand, but gnaw on what you don’t. The unique team of engineers who created TPS back then had a different perspective on business, and this is what we both seek and consistently miss by assuming too fast we understand what they mean. To this day, I regularly go back to Ohno’s writing and ask myself the same question I’ve been worrying about for the past 20 years: am I getting this right?

To help with Ohno’s books, a couple of other books written by Ohno’s contemporaries in more recent years are great helps to put it all back in context and wrap your mind about the mystery of what Ohno really meant. My personal favorites are:

To help with Ohno’s books, a couple of other books written by Ohno’s contemporaries in more recent years are great helps to put it all back in context and wrap your mind about the mystery of what Ohno really meant. My personal favorites are:

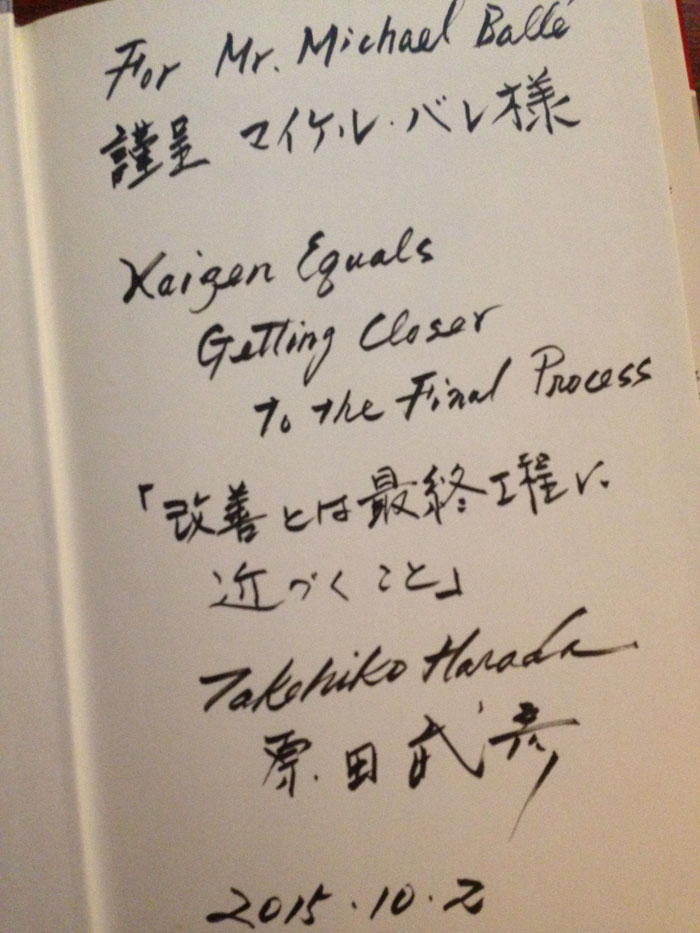

- Takehiko Harada’s Management Lessons from Taiichi Ohno, recently published by McGraw-Hill: It’s a fabulous book in the old style and takes you back to making cars in the sixties and seventies but with the benefits of modern insights. Most importantly, Harada, who was gracious enough to autograph my copy, shares a number of criteria to test whether we get it right or not, such as “does kaizen get you closer to the final process?” and “does kaizen bring decision-making closer to those who add the value, or take it backwards to managers in a meeting room?” This is an essential companion to the Ohno books and will comfort you in the queasy feeling that most of what we think we understand about TPS is wrong – which is also the fun of it. I had the honor to meet the author in Taipei and have had great discussions with Toyota sensei Joe Lee (one of Harada’s disciples) and here we have a rare example of the TPS original spirit kept alive in the 21st century.

- Takahiro Fujimoto and Koichi Shimokawa’s Birth of Lean published by the Lean Enterprise Institute: This collection of papers gives a great insight into what else was going on in Toyota around Ohno’s early efforts; the links between TPS and Total Quality; and a rare, fascinating interview of Eiji Toyoda himself where he shares his unique vision of a system built around individual contributions, from operator suggestions to full systems such as TPS.

Building on the Foundation

With the foundations in mind, you can then move on to explore Toyota’s actual working practices, and the best introduction to these are Jeff Liker’s wonderful series of Toyota Way books, starting with The Toyota Way to his profound insights on lean leadership with Gary Convis’ in The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership. Another must-read is The Toyota Way Fieldbook, which actually delves deep in the nuts and bolts of how Toyota ran its U.S. factory shortly after setting it up – this remains a landmark period for the adoption of TPS outside of Japan – and the fieldbook is worth a very careful read.

These two series of books should help you get your bearings on what Toyota did that remains exceptional and how these ideas are transforming much of what we understand about business. Now, for the response by non-Toyota businesses. Jim and Dan’s Lean Thinking essentially describes how other companies, whether Wiremold, Lantech, or Porsche responded to the performance challenge presented by Toyota. The best business book on the subject since Lean Thinking is, to my mind, Art Byrne’s Lean Turnaround, which clearly explains how traditional western business concepts can be used and changed to create real lean transformations.

There are many “tool” books around, and certainly, tools are very important in any lean initiative, but without reading Lean Thinking and Lean Turnaround, you’re likely to become over-involved with the “how?” and “what?” and completely miss the “why?” Lean Turnaround, in particular, explains how to link lean shop floor efforts to overall company performance as seen from the balance sheet and the P&L – a critical failing in most lean initiatives.

And then there are, of course, my own books The Gold Mine, The Lean Manager and Lead With Respect, which try to show what a lean learning journey looks like, and hopefully will help you to glimpse what lies ahead.

Quite a hefty reading list. However, there is no side-stepping it. To forge your own ideas about all the real-life examples you’re being shown at conferences or from kaizen efforts in your own company, you need to be clear on the fundamentals, and to understand the underlying tension between what Toyota does (how will we ever know for sure, Toyota is a large company and no one in there knows for certain either) and lean. Some of these cases are no more than traditional Taylorism masquerading under fashionable lean terms. Others are bona fide attempts at capturing an elusive “lean spirit” and looking for a different way of working. Others again, bounce off the various managerial fashions of the day such as Agile, Holacracy and so on. Each and every one is likely to claim the “lean” label, and indeed, your question makes a lot of sense – how is one to make up one’s mind.

First the Christmas tree, Then the Decorations

In the end, the same question applies to choosing a doctor: Who to trust? Who to trust particularly in ambiguous situations without any special inside information, and so many people blowing their own horns as the “true” source of lean – just count all the guys out there standing on a soap box, claiming to know what is “real lean” (yes, I know, I have to plead guilty as well). In this fog, my own three criteria, for lack of a better way are:

- Degrees of separation with Taiichi Ohno: How many links between a person and Ohno. For instance, I’m taught by a number of people who were taught by engineers who worked with Ohno – I’m separated from Ohno by two other people. This doesn’t mean I understand it any better, but that I have more authentic information.

- Reputation in the lean community: Yes, I know, not very satisfying, but still the lean community is now 20 years old and people kinda know who is who and what their strengths and weaknesses are, so joining the community will definitely help you orient. Conversely, a self-described guru who is not part of the community, and thus not part of the informal peer-review that goes on, needs to be looked at twice.

- Commitment to understand what lean is: The best lean thinkers I know – and I have had the luck to talk to and walk gembas with – are still working on this question: what is lean? Where is Toyota at now? Has it lost its way or remained true to the TPS spirit of the early days? What do we get right or wrong? A personal commitment to keep learning is a robust sign that this person is worth listening to, even though you disagree.

All in all, to answer bluntly, it starts with reading the classics to create the foundation which will enable you to orient in the lean thinking world: first grow the Christmas tree, and then you can hang on the decorations as you encounter them in training rooms, conferences, or kaizen workshops. I know it probably just feels confusing when you start but this is actually part of what makes the lean field great (and robust): We’re not talking about a few ideological books and rare spectacular cases. We’re now talking about an entire library of lean books and cases across the world (as portrayed by The Lean Post or Planet Lean). This is a serious field that has lasted over 20 years and will, in all likelihood, continue to grow. Diversity is great. On the flip side, the pressure to orient carefully is even greater as no one will do this for you – which takes us back to reading the classics.

Learning a lot from the post since even after three years formal lean practice promotion in the work. I sometimes get the question from my colleague that what is lean and what is not, to the one who has no idea they normally would like to know the most valuable answer. Even I share my thinking at that time, I still sometimes will ask the same question to myself, Do I understand right or not, do i practice right or wrong… help with post, what my take away is keep learning/practicing to fresh the understanding, do not give up anytime to pursuit of perfection. really thanks a lot.