Dear Gemba Coach,

I’m very interested in lean, but fail to see why you guys keep referring to Toyota. What does a Toyota plant look like and why should it still matter?

Fair point. I can’t speak for other lean writers, but personally, I keep referring to Toyota because I firmly believe they invented a new management paradigm and they keep being an inspiration to me.

What does a Toyota plant look like? Here’s a YouTube video of the Tsutsumi plant in Japan, producing the Prius.

I agree all car plants look the same, particularly if you’re not familiar with car assembly – the question is indeed: “What is so interesting about this?”

Here, for instance, is a Chevrolet assembly plant, and if you put both videos side by side, your first reaction is likely to be “same difference” – what’s the big deal?

Now, let’s put on some lean glasses and look for “one-second waste.” Why one second?

- First, because our lives pass by second-by-second so any second of someone’s life is precious and we shouldn’t waste it on muda.

- Second, because the one-second glasses will let you see that although the two operations look similar (why shouldn’t they, they’re both top competitors), at the one-second granular level, things are very different.

- Third, because the overall productivity of cars per total number of employees will be affected by the sum of these seconds that add up through the day.

- And fourth because eliminating one-second waste is really challenging and needs both kaizen and engineering cooperation.

The first thing to notice in the Toyota plants (though many other automotive plants do so now as well) is that although it looks like “mass production,” each car is unique, like people queuing at a bakery. Each car has a kanban card attached to it, with its identity and specs, in terms of options and so forth – which determines the work content to be done on the car.

What are we looking at? We’re looking at how fluid operator movements are because people are confident in:

- Their tasks,

- The sequence of tasks that make the job,

- The system and tools that support them to succeed at the task.

Old time lean; we learn to look at 1/ feet movement, 2/ hand movement, 3/ eye movements, and we look for struggle or waiting – any break in the fluidity and flow of the movement. We look for:

Struggle: Every time the operator places a part or uses a tool to place a part, does he or she struggle? Does it go right in, or, for instance, when they use a screw gun, do they have to hold the screw in place and look carefully if the screw goes in right. You’ll notice three things in the Toyota plant:

- The work “resists” very little. Think of last time you had to assemble an Ikea shelf; everything seems to be designed to either bite you or assemble wrong. Here, parts are mostly clipped in one deft move not needing to be fiddled with it.

- Operators often use two hands. To get a task done, they’ll pick up screws with one hand and the tool with the other in a simultaneous movement. This is really tricky because it takes out the eye movement, it assumes that operators will find what they need where they expect and don’t need to look other than a quick glance. This involves creating stations where it’s easy to orient oneself in space without looking.

- There is a lot of pushing but not much carrying. There is some, like occasionally taking a large part from the side of the line to the car, but mostly there are devices that support parts that can be pushed around and placed fluidly.

Such fluidity is achieved through 1/ training (and training and training) until the basics of each operation become second nature (which involves a lot of showing people what to look for and where to look) and 2/ kaizen, in a general sense. It’s not obvious at first glance, but this is not just operator kaizen, there is a lot of manufacturing engineering and even product engineering input in order to simplify steps this way.

The Ballet Effect

How do you get there? First, andon to visualize problems as they occur; all the grains of sand reality throws at you to make you struggle. As you see on the line, there is a rope all along that team members pull when they have a doubt and need a second opinion. Throughout the video, we hear the music of andons being pulled.

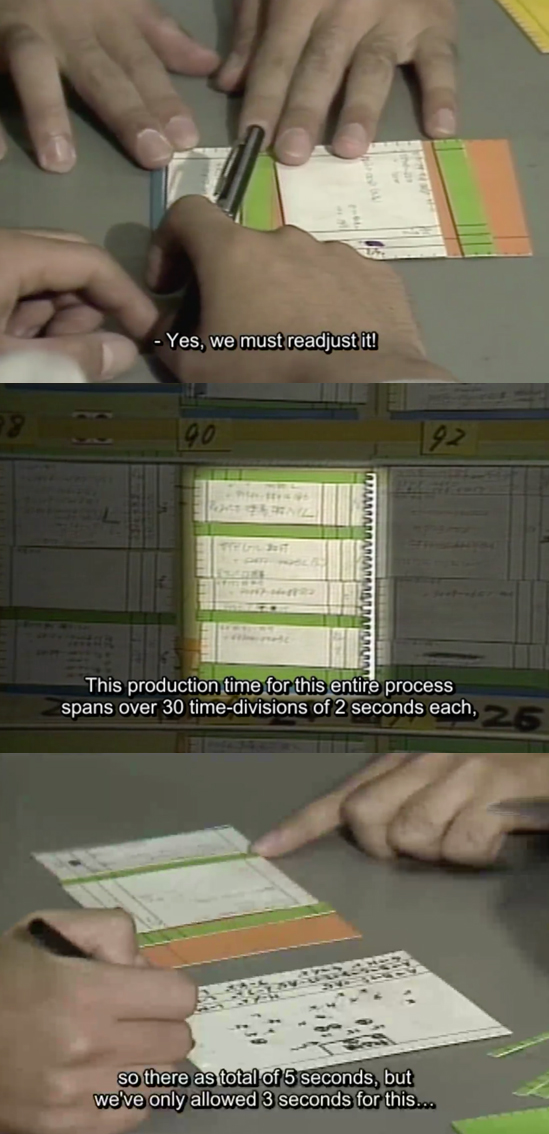

Then, Yamazumi. Here are three rare photos I have, dating back to the NUMMI days (yes, I know, 30 years ago now) that describe the process of coordinators looking at each station in great detail.

There is no way around it. The fluidity we see on the line is the result of andon (flagging every problem), yamazumi (looking for one-second waste) and kaizen (creative ideas and trying stuff).

Sequence: The second thing to see on the Toyota line is the “ballet” effect, how coordinated team members are when two work on a task. They seem to find themselves at the right time at the right place every time and never have to wait for one another. Beyond being confident in each task to achieve this, team members have to also be completely confident in what step to take next, in the sequence of tasks needed to perform the job.

Similarly, to eliminating struggle, this means delving in the details, with standardized work this time – clarifying time after time the exact sequence of steps to get the job right, as you would in sports.

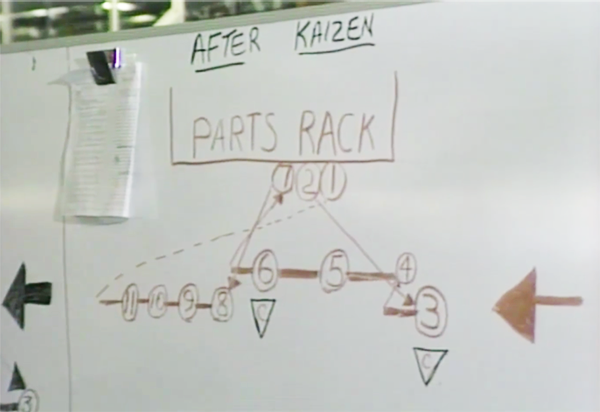

Here’s another example from the NUMMI days:

This means hours of working together to iron out detail after detail of what goes where: feet, hands, eyes.

Through kaizen – how would you improve this?

The third fascinating part in the Tsutsumi video is support. If you look at the tools themselves, they’re at hand, they follow the team members, they finish the job when human eyes are no longer required and they return to their at-hand position.

This is an illustration of the “separate human work from machine work” jidoka principle, and here again the smoothness and seamlessness in the way tools integrate in the work cycle is striking, and not through heavy automation either, but smart use of “karakuri” principles, simple, low-energy devices from, no surprise, more kaizen.

On the whole, it’s clear the pace is much faster and work denser in the Toyota line … so what’s in it for the team members? To explore this, it’s important to ask ourselves how to evaluate work, which is physical, certainly, but psychological as well. In psychological terms, humans feel good in a situation if they feel, essentially:

- Confident means a person can take responsibility for doing a job and not finding themselves defective or at fault in any way, not good enough. Confident means knowing how to handle the job, and knowing how to get better at it, which, in the previous terms goes back to mastering both each task and the sequence of tasks.

- Safety is essentially not anticipating any danger either from the work itself or from colleagues and managers. Safety on a lean line is procured by the andon system and a management that sees itself mainly as a chain of help, not a chain of blame. By creating stable teams, clear work areas, clear work, and a shout-out-for-assistance system, a lean line provides emotional safety for the members (if, of course, management takes interest and uses it the way it’s supposed to).

- Flow is an important psychological state in which time disappears because we’re “in the zone” fully concentrated on a task that comes fluidly and easily and that we feel is important. One-second waste is the key to creating such work environments where team members don’t have to be constantly interrupted by struggling with this or that and can do what they come to work to do: make good products.

- In control. Starting with the andon, then with 5S (teams have the responsibility to organize physically their work area), then the kaizen sessions and with the creative idea system – all the way to having an advancement plan for every worker, the lean system is designed to give as much control as possible to team members so they feel in control both of their second-by-second job, but also their progress in the company.

Company as Green Tomato

I personally feel that visiting Toyota plants to this day is important because it refocuses me on the basics: can I see one-second waste? This is easy to see in normal plants, but in a Toyota plant, much more subtle. Can I see variety? It’s also easy to think all cars are the same, just as we often believe all customers are alike, but of course, they’re not – a Toyota plant is a constant reminder of producing one-by-one. Can I see the engineering trick? Yes, kaizen is the key to fluidity, but in many cases, there’s an engineering input, either at product or manufacturing engineering level that makes it possible, from either Toyota or suppliers. It’s a constant challenge to look beyond the team-level kaizen for the engineering tricks of the trade.

To be blunt, I don’t believe that Toyota techniques can be copied outside of the specifics of the automotive industry. I do believe they’re an incredible source of inspiration when we try to think them through in software, healthcare, service or any other situation. Visiting Toyota lines remains both refreshing and challenging because while we struggle to understand, they keep moving ahead, giving us every more puzzles to figure out.

As well as always returning to the basics.

According to Prof. Takeuchi Nonaka, Toyota sees itself as a “green tomato,” (at 5:35 on video) — always growing, never ripe. I love this image because, as a writer, I know that a sense of incompleteness is what keeps people hooked on the plot. In might be just me, but visiting Toyota factories give me this sense of incompletion, of dissatisfaction – there must be a better way and hope because we can see people still looking for better ways without second thoughts. To answer your question, Toyota remains, after all these years, both challenge and inspiration.