Dear Gemba Coach,

We have been deploying lean visual management in my company for a while now, and I am troubled because I finally visited a Toyota plant and found far fewer boards and papers on the walls than we use – we seem to cover every surface. It made me wonder whether we’re doing this right.

To be honest, it’s hard to tell because Toyota sites differ greatly in their interpretation of TPS tools and, furthermore, car factories are so large it’s hard to get one’s bearings and a sense of perspective, but yes, I can see how this can happen.

The root of the matter, as often, is to figure out what Toyota is trying to do with its visual management. What I understand of it is that they are going for 1) problem awareness – revealing problems, to support 2) problem-solving, which means people learning to make better, faster, on-the-spot decisions. This involves a mix of “daily management” – visualizing what we have to achieve right now – and “space to think” – thinking more deeply about our problems, which is not an easy balance either to understand or to achieve.

Some months ago, I had the same experience you had, I was kindly invited by a management team to accompany them in a Toyota plant visit, and participate in the followup discussion of where they were in lean – and particularly their visual management. After weeks and weeks of gemba walks with the CEO we came up with the following shortlist of what visual management should achieve:

- Is the game understood? Can we, standing in the area, intuitively understand what is at stake, at play, and how to play the game?

- Are the expected gains clear? Can we see clearly where the team is trying to progress and how that will up their game in the current context?

- Is the problem-solving energetic and thoughtful? Does the team tackle its own problems, and do they both react smartly and quickly on the moment and then think more deeply about causes?

- Is initiative apparent and can we see where to support and help? Is the team trying to do something new and monitoring its own progress so that, as management, we can lend them a hand and clear some obstacles from their path?

- What can we learn from their experimenting? No point having scouts if we don’t listen to their discovery reports – every frontline experiment should teach us something we didn’t know about both the business and our own organization?

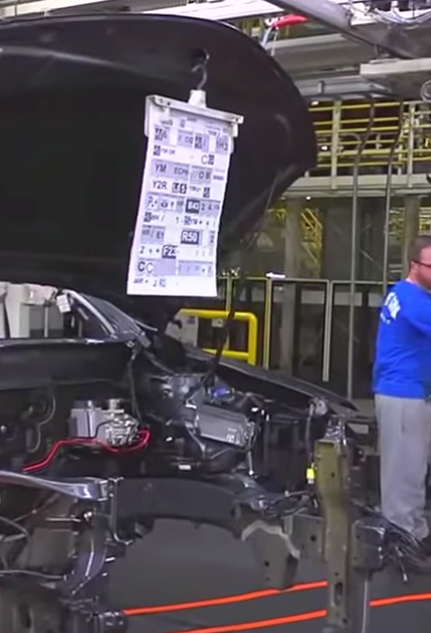

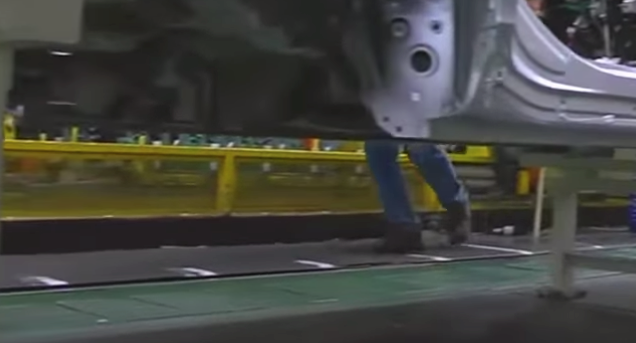

The form of it varies, but in every Toyota plant I’ve seen, the game is pretty clear. If we look at a Toyota gemba you’ll notice (see pictures below):

- Pull: Each car has its own kanban, and is an individual in a just-in-time sequence, assembled as close as can be to customer demand (with the required flexibility, which also means bringing the right components to the right car at the right time).

- Takt: Each team member has a set amount of time to do the job, which is visualized on the floor.

- Andon: The andon chord makes it obvious that if you have any concern about the quality of the work or keeping up to takt time, call for help.

- Progress boards: Progress is visualized across the factory with electronic displays showing the andon calls, but also, actual versus planned, in many cases overtime needed to achieve the plan, and the success ratio of plan versus target.

The shape and form of these elements varies between factories or, indeed, from area to area in the same plant, but the basics are always there.

In terms of “paperwork” visual management, you do find some, mostly as visual standards, but not that many, which might explain your surprise.

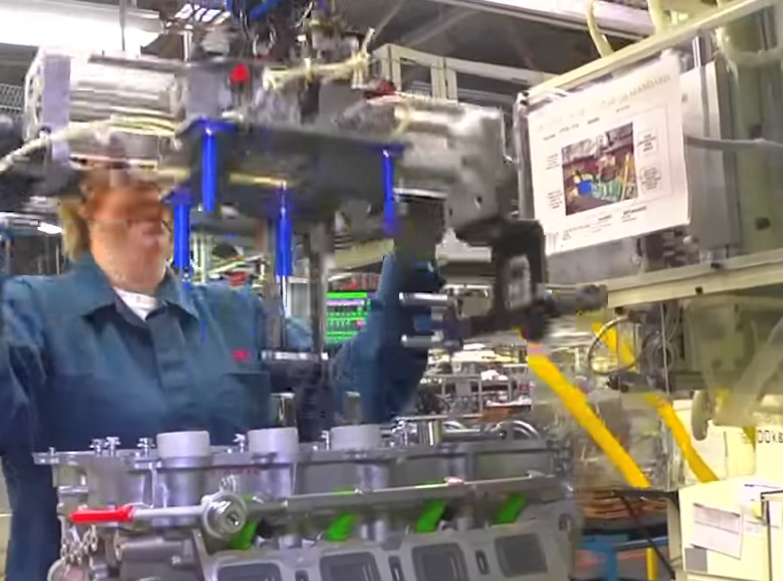

This other fascinating video shows that kaizen on the line is clearly about shaving seconds (or fractions of seconds) from the work needed to assemble a car. The gains expected from improvement are clear, so people know where to put their minds to work.

Visual management is about helping intuitive team members with their next step: where should I look, what do I do if this happens, what do I need to pay attention to. Visual management has to be set up carefully because too much visual information actually distracts and defeats the purpose of visual management.

Making sure the game is understood and the sought after gains are clear is harder than one would think, mostly because management is never quite that clear about what they’re doing. As a result, so-called “visual management” fills up with too many indicators, too many improvement projects, and all these things management does to make sure that, in the end, things stay exactly as they are because no one at the coal face understands what, exactly, they’re expected to do.

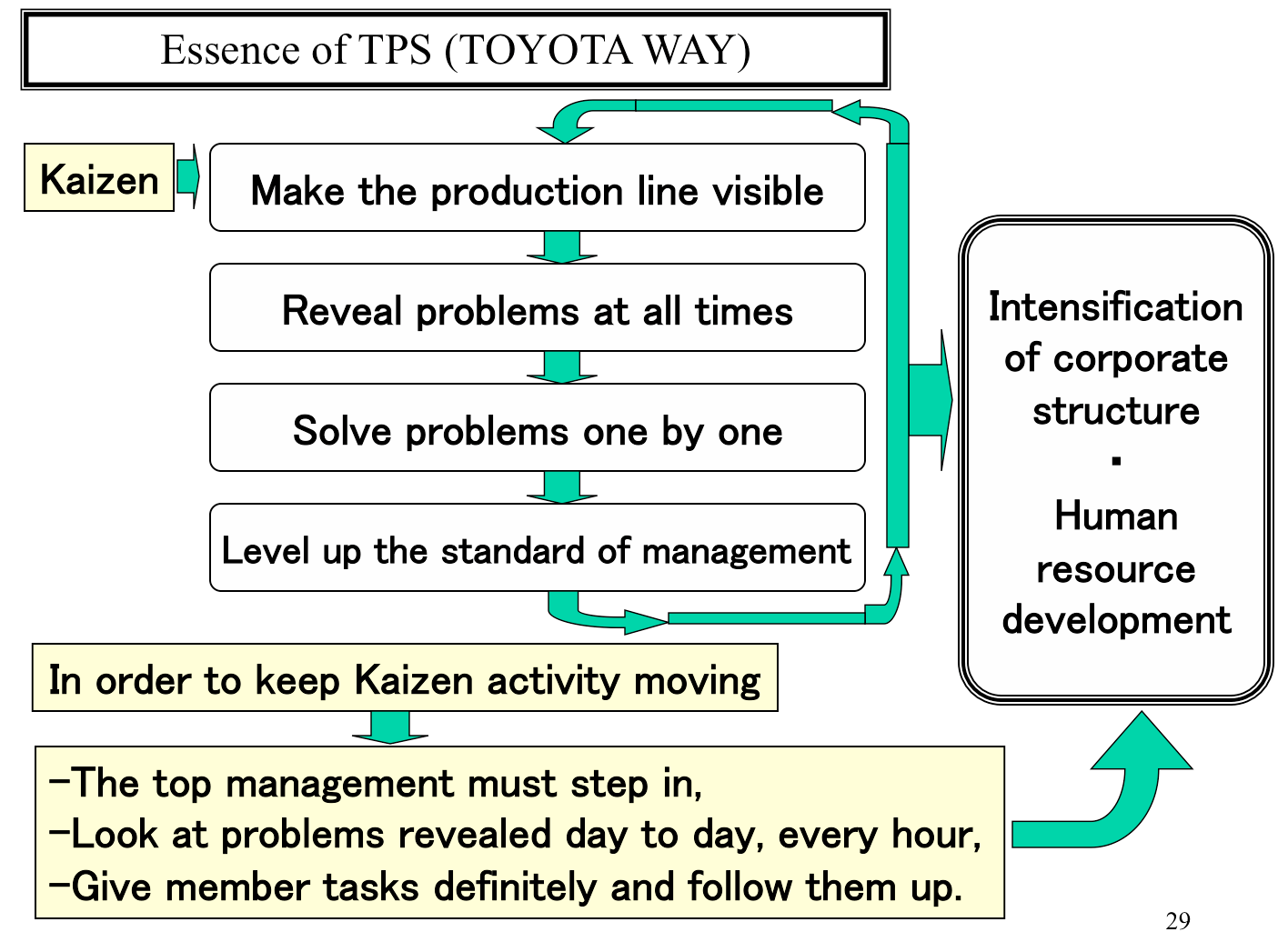

The next step is looking at the quality of the problem solving. Kaizen, as explained to me by Takehiko Harada, the author of Management Lessons From Taiichi Ohno, is to bring value-added work closer to the final process.

This gives us a yardstick to evaluate whether the problems solving is problem workaround – shifting the problem to another part of the system – or actual problem solving, which is changing the right thing so value gets brought closer to the customer.

Actual problem solving will be harder to spot during a Toyota factory tour, the areas (below) where it occurs are easy to pass by, and meetings happen at set times. Here is another video showing daily problem solving at a Toyota sister company, Toyota Material Handling: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nFu4FFgbMY4

And, again, the format of these activities is not standardized across the company. More importantly, having activities ensures the quality of the problem solving: the awareness, the deeper thinking, and the creativity of the countermeasures.

Which brings us to the management’s part: looking for where it can help. When the visual system works well, what teams are trying to improve is quite obvious, such as, in the Toyota plant, the teams working on the AGV – automated guided vehicles – to bring the parts just-in-time to the line.

When teams try to do something like that, clearly management can help by supporting them and removing roadblocks from their path. This, in turn, needs genuine interest and involvement from the managers into what the team is trying to achieve, and not throwing in ideas or recommendation. This is where we see one of the breakthrough attitude changes of management:

Command and control – Challenge (orient) and support

In a Toyota plant, these projects will be found in “obeyas” and not necessarily visible during a plant visit. Here’s one I saw in Toyota’s Melbourne plant:

Last but far from least, the point of all of these activities, as my father’s sensei once explained, is to improve the standard of management, so that the whole company runs better.

And this means learning. Visual management that teaches you nothing more, either about what’s going on in markets out there, or the way people are working in there, is “good news only” visual management – designed to keep the bosses happy and out of team members’ hair. What we’re looking for is “bad news first” visual management that truly reflects a culture of problem solving, which means curiosity, openness, and engagement from management.

To answer your question more directly, how about applying lean thinking to your visual management. Rather than try to determine the “best practice” way of visual management, reflect on 1) clarifying the purpose of visual management, and 2) start listing all the known mistakes about visual management – to avoid them and discover wholly new ones. The CEO I mentioned is doing just that and has already learned not to confuse daily management (indicators and immediate countermeasures) with “obeya,” which comes from engineering, and is all about creating a space to think to explore problems more deeply.

You ask an excellent “awareness” question: Toyota’s visual management is not as I expected, and different from ours. Don’t try to resolve it by adopting what you believe is closer to what you saw in the plant – it was one part of one plant. Try instead of thinking more deeply of what the ideal visual management could be like, discovering the many pitfalls, and steering your teams to build their own in a way that works for them, and for the company.