Dear Gemba Coach,

We’ve deployed obeyas all across our organization, but I can’t see any significant improvement in our results. We can better see which teams perform and which don’t, but the good teams stay good and the poor ones poor and I’m not sure the increased performance is worth the effort. Are we doing something wrong?

It’s hard to say without visiting your gemba, but let me ask you one question: have you deployed “obeyas” or “daily management systems”?

The greatest waste in management is to have leaders do the job of their direct reports. Not only does that take any initiative away from subordinates, which turns them into dumb compliance machines, but it also means that the execs are not focusing at their level and doing their leadership job. In any operational structure, the first panic reaction whenever a crisis hits is that everyone starts micromanaging the people under them, rather than do their own jobs.

Let’s start from the gemba, and build the system back up, shall we?

At the value-adding level, lean theory tells you operators need everything to produce good parts: They need the right number of trained people, a stable volume, a sense of getting ahead, a deep understanding of OK versus not-OK at each station, components that they need not check before assembling them, machines that work as they’re supposed to. Operators need also to feel they own and control their work environment and have a clear way to deal with unusual situations as well as confidence their efforts are recognized and an understanding of their own personal future in the company.

Lean practice, therefore, visualizes this in the line through visual management: no powerpoints or graphs, but physical devices to help operators orient:

- Kanban cards to be autonomous on what needs to be done next,

- A shop stock to own one’s production until needed by the internal customer,

- An andon cord or andon buttons to call for support when something is off,

- Visual identification of containers and machines to make sure all is in the best order to support standardized work,

- Visual standards to distinguish OK versus Not-OK,

- A board to see whether they’re ahead or late on the schedule and note problems.

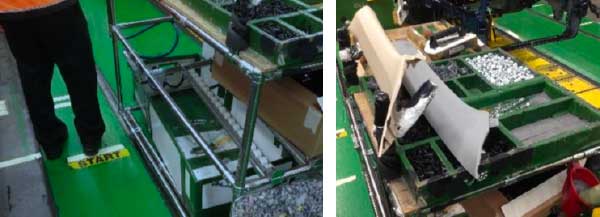

For instance, in this picture (Courtesy of Toyota Australia) we can see visual management – in the clarity in which it’s easy to see whether things are OK or not-OK at first glance:

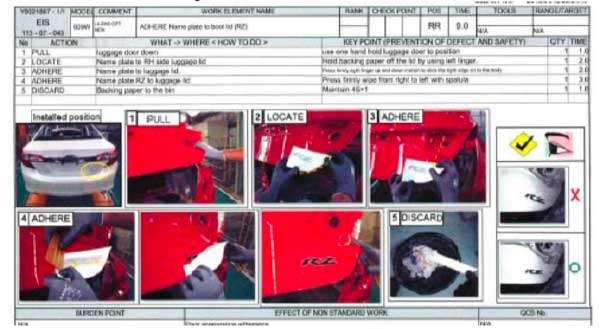

And clear work instructions:

Visual management is not there to control team members’ behavior but to guide their eyes: eye movement, hand movement, feet movement – to make it easy to get the job done right first time.

The whole point of the visual management system is to support team members in their work, at takt time, and to make it easy for them to spot abnormalities and pull the andon cord.

Daily Management System

Now, obviously, keeping a work environment in top conditions so that team members can do a top job easily demands attention. Every day, friction will occur, in the form of either, small things that get out of line and have large consequences (the grain of sand in the cog that stops the machine), then every day we will discover some things that we didn’t know that change how we think about what we’re currently doing, and finally, each person has a different opinion on what should be done and in what order.

Therefore, at frontline management level, whether supervisor or group leader depending on how the jobs are titled, we need a system to make sure things are constantly cared of and kept in check.

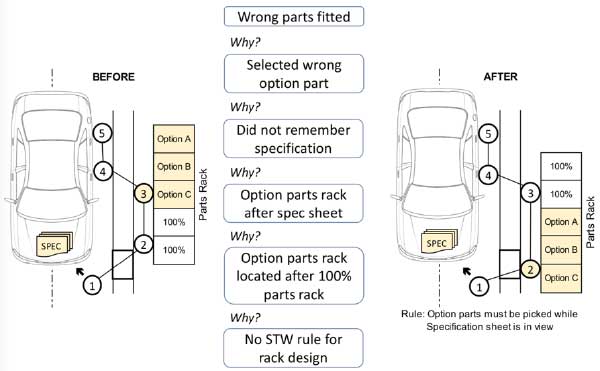

The daily management system is essentially about visualizing problems and making sure we get around to solving them. It will be made of:

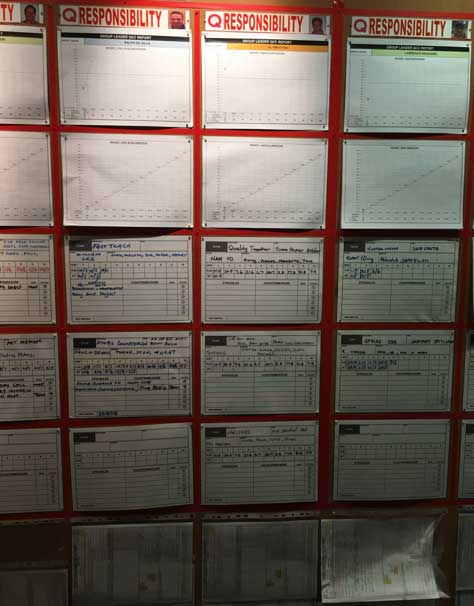

- Key indicators (starting with safety and quality), and most importantly making sure dangerous situations and defects are counted at every step of the process – here’s one from a Toyota plant in China:

- A checking routine for frontline management, by which you ensure managers go to physical control points regularly,

- Analysis and countermeasure plans of problems identified,

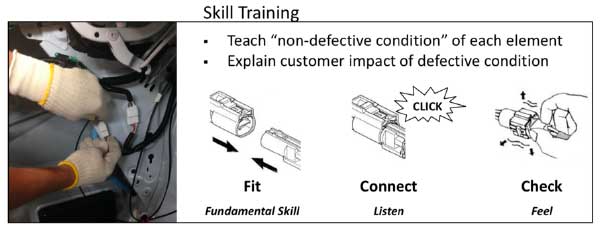

- Competency matrix to see where we are in terms of people leadership in each cell and skills training:

- Kaizen efforts so that teams own their own work and commit to routine improvement:

- Suggestion follow-up system to make sure creative ideas are encouraged and supported,

This daily management system will typically appear as a wall full of indicators and countermeasure plans:

In the auto industry, we’ve been doing this since the mid-1990s, and I clearly remember that at both Valeo and Faurecia we had pretty much the same experience that you describe. Although all plants had learned to get good audit grades on “the system,” all this delivered was routine taking care of things, and rarely was actual performance improvement delivered across the board. It did highlight areas in difficulty, and mostly the problem was managerial.

The “obeya” in Toyota had a very different origin. As the story goes, the chief engineer of the Prius was challenged to come up with a car that would run double the distance on the same fill-up YET have the same spaciousness as a normal one. He found himself investigating a large range of technologies and talking to all sorts of experts and it kind of got out of hand, so he created one big room where all these various technologies would be exposed for people to understand what each person was doing and where they were going with this.

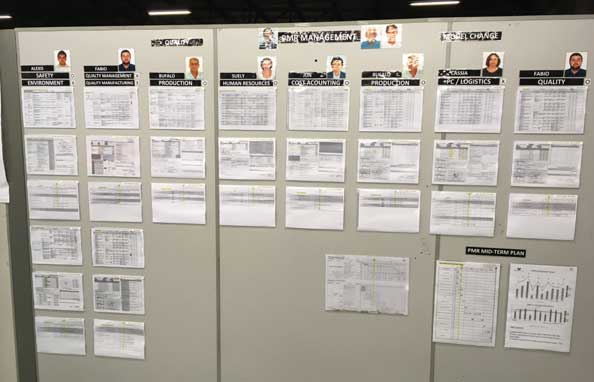

Obeyas are not about control, but about facing challenges, discussing the hard problems, and sharing how they interface with each other in the complete system that is a company, or a plant. For instance in this obeya wall, courtesy of Boshoku in Brazil, managers explain how they’re working on various systems to improve how the plant works as a whole:

In this other obeya, each function has a board to explain what they’re working on purchasing to production engineering and product changes for the local market:

These obeyas are really about solving a huge challenge in any organizational structures: better interfaces so that we all understand what each other is doing and how this fits together in order to have a business-level result.

The purpose of obeyas is very different from that of daily management systems. Very early on, Eiji Toyoda realized that one cause of Big Company Disease was functional specialization and rivalry. He created countermeasures, starting with the total quality management system in order to pierce the silos (in fact, this is also what a pull system with kanbans does in production). Obeyas are a thinking space, not a to-do list follow-through space:

- Are we facing solving the right problems?

- Do we all understand the situation the same way?

- Do we understand what each of us is trying to do?

- How can we help each other to achieve overall performance improvement?

One thing you might want to check with your obeyas is whether you’re making the most common mistake I see in companies deploying lean: using a version of daily management system at the executive level.

Rather than help performance, this actually reinforces management’s tendency to keep their heads down and force action, putting pressure on their subordinates and often doing the job of the guy under them. And, as we discussed, this is the worst waste you can create.

Tools are tools – if all you know is a hammer you’ll see everything as a nail. The origin of tools and their purpose matters. Visual management is about guiding team members’ attention in doing their daily jobs well. Daily management systems are about helping frontline managers solve production condition problems week after week by following indicators and following through with countermeasure plans. But obeyas are about fostering a greater cooperation between department heads so that they understand and face challenges better and solve customer problems at interfaces in the system in order to, every day, create more enabling systems for employees to add value.

Obeyas are thinking spaces far more than doing spaces. They are a space for free exchange of knowledge, opinions, and ideas so that we face the pain of real learning together and find the motivation of real progress as well.