Dear Gemba Coach,

On the gemba, we have many problems to manage every day. People don’t seem to learn from their experience. Is there any way to teach the people when they don’t learn from their own experience?

Thank you for a very deep question indeed. The short and long of it is that people do learn from their own experience, but not necessarily to solve the problem. For instance, one of the most powerful concepts in psychology is “learned helplessness.” When animals, or indeed people, are stuck in a situation with bad stuff they can’t control, they learn not to try any longer. After a while, they grow anxious and despondent and can slip into depression. This is learning as well, but not the kind you have in mind.

By learning, I expect you mean adapting their responses in order to perform better at solving some specific problems. As opposed to simply responding to a situation, learning to respond better requires a deliberate effort both of will and skill. This is very different from the general assumption that by repeating a situation or an action one naturally “learns.”

More Than Repetition

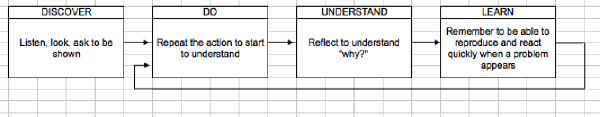

For instance, one of my students is working on an A3 on learning to explore his job as a lean officer. His first instinct was to describe learning as:

I suspect most people would agree with him.

The glitch in the thinking is that it completely bypasses wanting to learn. For this process to actually produce learning, at the “do” phase, the learner must strive to reach for an ideal, not simply repeat.

Without thinking much about it, we assume that repetition leads to learning, and to some extent it does. We feel that from repeating our daily commute we no longer have to think about how to go to work, we know – it’s automatic. The more we practice and repeat, the greater the fluency, and the higher the recall, so we intuitively think this is “learning.” In truth, learning is something else altogether.

Let’s take a real learning situation. Because it’s always easy to fall into the “they don’t want to learn trap,” I’ll use a case where I’m personally struggling with learning.

My own personal take on lean is figuring out how the Toyota Production System (in its wider sense) transfers out of Toyota and into other situations. This means that I try to (1) learn more from Toyota, (2) try it out outside of Toyota and (3) share the results and encourage debate so that we can collectively figure it out.

For decades now (since the 1980s at least), Toyota has been a leader in energy performance and all green things. It’s corporate vision actually spells: “Through our commitment to quality, constant innovation and respect for the planet, we aim to exceed expectations and be rewarded with a smile.”

I’ve been working at quality and innovation for decades, but to be consistent with my original vision, how well am I doing with “respect for the planet”? Not so good. As you can see right away, I am facing three learning problems:

- Taking it up as a challenge: There’s a feeling that we’re busy enough doing what we do that we’ll do the green stuff when we’ve grown up – and postpone it year after year. It’s only in the last couple of years, thanks to Kelly Singer, that we got an initiative started https://leangreeninstitute.com/

- Learning to do it: What is specific about lean and green? Our first reflex is to practice lean, on the one hand, learn about green on the other, and try to blend them – which is not looking for specific lean and green techniques and activities.

- Thinking about it on the gemba: Seeing it as relevant and arguing for lean and green projects even though the business has many other immediate problems and doesn’t see the direct relevance of green to its here-and-now issues.

Learning is far more than acquiring a new habit. Real learning has three different challenges: How do we really learn new stuff? How do we challenge our habits to apply this new knowledge? How do we click when this new knowledge is relevant?

Changing a habit to learn a more effective response to a situation won’t happen just by repeating an action. Habits are never “changed” as such – they remain imprinted – but they can be smothered and replaced by another behavior. Still, the initial response, particularly when surprised or tired, will for a long time be the original habit.

Willful Repetition

Real learning doesn’t occur simply by repeating – it needs to be willful. Before trying to learn something, you have to envision an ideal state, find an example to copy, figure out something new, and strive for it. Neurologically, learning doesn’t occur when you feel you succeed – it occurs through the struggle. It’s precisely when your mind feels blank or you search helplessly and messily for an answer that new connections establish themselves at the neuronal level.

Real learning also needs trying the same thing again and again in different contexts. This is the “child looking into the well problem.” None of us would walk past a child looking into a well without pulling them back, whether we know them or not. Now, in the green case, will I stop and point out a green issue when I walk past one on the gemba? I’m not so sure. I need to (1) know more to see it, ( 2) feel it’s important enough compared to the rest and (3) have some idea about what to do about it. Think of multiplying these three probabilities and you’ll see how unlikely it is that I will stop at first if I don’t force myself to do it (and step way out of my comfort zone in doing so).

Learning is a willful act, and it needs:

- Clarifying what we need to learn: This is often far from obvious. For instance, in lean, many people think that by avoiding tool changeovers they stabilize the process and so keep quality under control. Alternatively, frequent tool changes force you to go deeper in your quality issues (first part needs to be a good part) and so learn about quality.

- Understanding the loss function we want to reduce: For instance, if we keep with the quality topic, do we want to reduce quality complaints or percentage of defective parts or non-right-first-time. Any of these measures will reveal some aspect of quality, but not necessarily the same. According to context, choosing the function we want to build the learning curve on has a large impact on what is learned.

- Choosing a learning method: Where do we look for the next step? The mystifying thing about learning something new is figuring out whether we’re actually doing something new or repeating what we already know without realizing it. To avoid old habits creeping in, we need a structured method that shows where the next step is.

- A good idea of where to reinvest the gains: Because learning is hard, knowing what we want to do with the performance once we’ve learned to master this or that is essential to maintaining motivation.

Not surprisingly, all of this is quite difficult, which is why we learn better with a teacher who helps us clarify:

- The right way to do the new stuff

- Correct what we do in detail so we understand what we’re trying for

- The right attitude and aims of the new knowledge.

Because learning is so contextual, we run into the further difficulty that some local cultures are learning-friendly or, on the contrary, learning-averse, (and you wouldn’t know it from the way they speak, you need to look at what they do). Learning averse cultures will stop any learning attempt by mainly (1) reminding you to first do the job you’re supposed to do before looking at something else; (2) question the need to look deeper into anything and keep side-tracking you with red-herring “yes but” arguments to show that new learning is both unnecessary and a waste of time; and (3) spread a “martyr” syndrome in which every new thing asked is a mountain and every small step done requires endless praise and encouragement.

Fake Learning

Learning-averse cultures can easily masquerade as learning cultures. The way to spot them is to look at whether people are free to attempt things on their own or whether every new step requires more advice, more training, more validation, and so on. For instance, many lean programs are in fact learning-averse. People feel they need more support to do any kaizen: more lean coaching, more hand-holding by consultants, more recognition from the top brass, and so on. This is a good business model for those who sell the support, but sure enough a sign of a learning-averse culture disguising itself as a learning environment.

In the end, a large part of why people don’t learn from their experience is that their environment is not set up for learning. First, they are not encouraged to learn and managers are picked for their troubleshooting abilities, not their learning skills. Secondly, there are no challenging-and-safe places to actually learn anything. Thirdly, real masters, mentors, teachers, trainers, sensei, are not readily available. Finally, the gains from learning are captured by someone else and there is no recognition for doing the hard work of learning. In such an environment, experience is only habit-forming and reinforces the way things are done today, with very little learning, as the few who would learn from experience need to fight hard against a context that smothers any attempt at breaking the mold.

To answer directly your question, when people don’t learn from experience, you’ve got to challenge yourself on whether you (1) have a robust enough learning theory, (2) are creating the right learning environment around you and (3) can you spot the people who really refuse to learn and not confuse a lack of motivation with a personal attitude. Never easy, but always fun!