When Covid hit, we saw businesses we benchmark around the world jump into aggressive “do this/do that” mode — suddenly forced to make decisions about whether to shut down or remain operating, issuing instructions, and making rules about a situation no one had seen before and, for sure, no one understood completely. We also knew we had to act fast and establish new rules to protect our people and customers.

But what rules? How could we know what to do from our seventh-floor glassed-in office at headquarters?

We took a deep breath and reverted to what we had learned from the authors of The Lean Strategy. We asked ourselves how to frame the problem. We went back to our teams and asked them:

- How will you protect your staff and customers from catching the virus?

- How do you find cars for customers who really need them?

- How do you deliver to customers without physical contact — but at the same time, not without human contact?

- How do we visualize an end to this crisis?

We discovered from listening to the teams across the country with common problems yet a range of experiences. Each was in very different situations (some locations were in Covid epicenters while others remained unaffected) and had wide-ranging dispositions (from managers who thought we should err on the side of absolute caution to those who dismissed the whole thing as a media-driven panic). We also realized they all had far more access to local information than we did.

We began to ask the same basic questions in a newly established community of practice: Are you sure you’re safe? What customers are showing up? (We learned that many worked in essential services, such as nursing or firefighting, and needed a car because of transport disruptions.) What initiatives have you taken? A consensus quickly formed, prompting us to find a balance between keeping people safe and continuing operations — we were relieved that we were spared major Covid incidents. On reflection, we feel that we emerged stronger from this crisis, more closely aligned, and with a more intense sense of team cohesion because we used framing to meet the challenge together.

What is ‘Framing?’

Framing, in this context, is an angle of view, a way of looking at things, specifically how leaders view work processes. Framing helps leaders align their teams because how leaders frame situations disproportionately impacts how teams do their work. Leaders spend their time explaining how they see the work challenges, what they aim for, and what they expect people to do, and then modeling how to respond. (Often, they do so without being aware of it.) When the frame is clear and consistent, people naturally follow it, creating a powerful feeling of team unity. When the framing is vague and inconsistent, people stick to their own frames and compete over whose frame to follow. What we see in politics is a very public — and legitimate — war of framing, which often sounds somewhat ridiculous because the framing of political discourse is oversimplified to be more salient and draw people to the cause.

… how leaders frame situations disproportionately impacts how teams do their work.

An example is Western business culture’s near-obsession with framing work practices as behavior and behavior change. Since Taylorism, we have come to believe it is self-evident that a worker’s behavior should follow the work standards given to them by the experts. Also, behaviorism taught us that people behave according to habits that can be reinforced or changed through the proper rewards. The research literature is full of this behavior or that: leadership behavior, worker behavior, etc. If you accept these ideas about work practices, you see work practice through their framing.

However, we can imagine a different framing. The hand, for instance, is guided by the eye: What we look at guides the hand’s movement. So it is with behavior: What you see influences what you do. With this different perspective, we would not be worried about behavior per se but about what we ensure people look at or see in a given context. Show them appropriate information, and they will react sensibly and most predictably. So our management practices would then shift to choosing what we show people or ask them to look at and how we construct visual feedback — indeed, visual management and go-see at the gemba — instead of relying on a boss’s directive or a reward system.

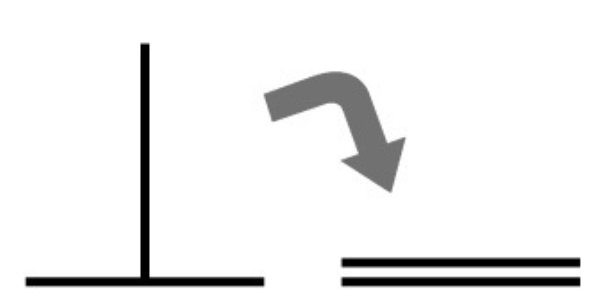

In Workplace Management, where author Taiichi Ohno calls for no less than “a sort of revolution in consciousness,” he establishes the prevalence of misconceptions, stating early in the book that we get things wrong half the time. He shares the optical illusion where two identical lines form an inverted T, where the vertical line invariably appears longer:

Ohno explains: “There are so many things in this world that we cannot know until we try something. Very often, after we try, we find that the results are completely opposite of what we expected, and this is because having misconceptions is part of what it means to be human. While it is easy to persuade people by trying out the optical illusion, it is difficult to prove that the ideas in your mind and the thoughts in your brain are, in fact, misconceptions. In many cases, when a person has an idea or makes a statement they believe is correct, they find that it was a misconception. When you try your ideas, the results can be contrary to expectations.”

This sophisticated thinking anchors Ohno’s insights and the subsequent development of the Toyota Production System. Indeed, Fujio Cho, a former student of Ohno and legendary president of Toyota, explains in a foreword to his book that “The Toyota Production System pioneered by Mr. Ohno is not just a method of production; it is a different way of looking and thinking about things.” No mention of behavior, only looking and thinking: a different frame.

Our daily experience of the world feels seamless and complete. We all experience reality “as it is.” Or so it seems. In fact, what we experience is a seamless simulation of reality that runs on the software of our brain. This simulation is constantly corrected by our senses, with the brain continuously adapting it to what it sees, hears, and feels (the simulation also runs at night, with the senses disconnected, as we dream).

As Fujio explains, Ohno’s “conviction was that the truth exists in the gemba (the workplace where the action is happening) whereas theories are just the product of imagination.” This statement conveys a profound insight, and brain science has taken decades to catch up.

Your brain runs a seamless simulation of reality, continually correcting what it sees according to the explicit, concrete information picked up by your senses, with more than 50% of the cortex devoted to processing visual information. The brain also interprets situations according to tacit (implicit, unexpressed) knowledge, ideas, and values that make it select what is relevant. If you go to the gemba and observe how an operator works, do you look at his hands? His feet? Or his eyes (what is he looking at)? If all three, you’d be using three different frames.

Framing is Focusing

A mental frame is like a frame you put around a picture: it orients your eyes toward what you’re looking at and enhances it. A frame is how you see a situation and approach an issue; it’s a non-verbal mix of what you find salient, what intention you see or have, and what you think is OK. Thus, a frame helps you decide whether something is a problem and what is an acceptable solution.

For example, did you get your Covid vaccine shots or not? Either way, you will have reached a decision and acted on it (a behavioral conclusion) according to how you see the epidemic situation, what you believe about vaccines, how you feel about people for or against them, and mostly how surrounded you are with proponents or opponents to vaccination. The concrete, gemba-based facts are the same for everyone. However, interpretations and resulting decisions/actions will vary widely according to the internal psychic flow of each person’s experience — the simulation their brain builds of how the world works.

Overcoming Framing’s Limitations

Frames are an integral part of the human experience. In his classic novel Daniel Martin, John Fowles describes how Daniel gets so angry looking down from a high window at a cop walking toward a homeless tramp and talking to him — only to see the policeman then share a cigarette with the man and walk away amicably. On a hospital gemba visit, one of us saw a doctor berate a nurse because she hadn’t cleaned a patient’s room when scheduled, only to hear the nurse (in tears) explain that the family was surrounding the dying patient and didn’t want to interrupt and shoo them out.

As Ohno intuitively grasped, our frames are, first, most often wrong or incomplete, and second, in a constant state of flux. When two persons meet, their frames collide. If one person convinces the other, the two people align; if not, then conflict appears.

Frames are tricky. First, they are mostly unconscious — to us, we experience “reality,” and are seldom self-aware that we are experiencing this reality through a frame unless it blows up in our faces. Second, this reality is easily primed by surrounding visual cues. As our brain constantly tries to answer the question, “What is going on right now?” it catches salient signals from the environment, from how other people around us behave, and processes them without letting us know. Hence, we get carried away with surprising decisions or behaviors that seem out of character simply because we were surrounded by “priming” cues pointing us that way.

Framing Becomes a Framework

Once you realize the power and omnipresence of frames, you suddenly see the importance of frameworks. Frameworks are explicit frames, shared constructs that enable collaboration. For instance, the Profit and Loss framework makes you view a business, first and foremost, as a profit-making machine (and not, say, a service-providing community for the benefit of society) which starts with turnover, minus the cost-of-goods sold, minus operating costs, plus or minus financial income/expenses, plus or minus exceptional income/expenses and shows the bottom line. This framework is so common and powerful that most people cannot avoid thinking of any business in those terms.

Digital innovation is another framework that has become dominant in the previous decades. Under prevailing norms, disruptive innovation is funded at a loss by capital injection from investors until the new product or service reaches a critical mass of customers, prices can be increased, and, combined with volume cost effects, become profitable. One of the visible impacts of this new frame has been to shift prudent financial thinking of looking for healthy EBITDA to a vaguer “storytelling” frame, where future cash flow is promised based on the strength of the “story” and the willingness of investors to fund the story. We’ve seen this in 2008 and today. And this new framework has had staggering impacts, including the neglect of maintenance activities (seen as an expense) and the rash of mad innovation gambles — at a tremendous cost to society.

Addressing Rapidly Changing Business Conditions

Nicolas and I share a longstanding passion for uncovering and understanding business models and the frameworks people build on them — and there are many such frameworks, such as finance, bureaucracy, Taylorism, operational excellence, agile, digital 4.0, etc. Of all these frameworks, we have concluded that the Toyota Production System is the most robust and most likely to lead any company to succeed in rapidly changing circumstances. There is never a time when satisfying customers is the wrong idea, when fixing quality problems earlier in the process is the wrong idea, when reducing lead times is the wrong idea, when balancing workloads and capacity is the wrong idea, when engaging team members in learning their craft and conducting kaizen is the wrong idea, and when building mutual trust between management and employees is the wrong idea. The TPS is a remarkable framework.

The TPS is a remarkable framework because it was built on remarkable intuitions on thinking and framing, starting with Toyota’s founders and made concrete by Ohno; because it is the result of the experience of thousands of engineers over decades, not the brainchild of one person; because it addresses the processes that create business results, not the results themselves; and because it is a learning system, not a set of best practices.

The downside is that these same features that make the TPS so powerful are also what makes it so challenging to learn — it’s a complete system, and although its explicit dimensions (the “house”) are clear enough, the tacit practices can only be acquired through long practice on the gemba, as Ohno fully understood. Consequently, it is hard to teach at scale — the system, including its huge tacit side, is mostly taught at Toyota from teacher to student in a line of “sensei” conveying the company’s experience and traditions in a chain that goes back to Taiichi Ohno himself. Another challenge is that other competing frames, such as Taylorism, are so strong and prevalent, making it easy to misinterpret TPS without an experienced teacher.

Practicing the TPS on the gemba has led us to change our framing within Aramis Group (or at least, attempt to). We used to believe, as most companies do, that a leader’s role involved the 4Ds: 1) take charge and define the situation, 2) decide on an option, 3) drive the implementation, and, unfortunately, often 4) deal with the unexpected consequences of the implementation. Practicing the TPS on the gemba has made us painfully aware that Ohno’s insight was correct: Most of our ideas, out of pure imagination, are proved wrong when confronted with the reality of customer experiences, team member contexts, and things moving (or not) on the shop floor.

We are therefore trying to adopt a different decision-making process based on the 4Fs: 1) find the real problems on the gemba, 2) face the hard part of these problems — what we currently don’t know how to do and must learn, 3) frame these challenges in ways that all people can understand and contribute to addressing through kaizen, and 4) form solutions from sharing and discussing experiences until paths to success are clear in very troubled market conditions. Our reframing of the decision-making process has dramatically impacted our financial success and our adaptability to very challenging and volatile market conditions.

Building a Lean Operating and Management System

Gain the in-depth understanding of lean principles, thinking, and practices.

Very insightful and shows the intuitive skills of the author

A very clever essay.