Dear Gemba Coach,

Why, in your experience, after all these years of preaching lean, is it still so hard to convince executives to adopt the lean spirit?

You ask an interesting and difficult question. First, from the gemba, it’s not so black and white. Most companies I come across these days have a lean initiative in some shape or form. True, these efforts are often closer to classic productivity or cost-cutting drives, but they do use the lean vocabulary and lean tools. Why isn’t that considered “real lean”?

Another way to ask this question is how come with all the lean programs under way, there are so few transformative experiences as described in Lean Thinking, such as Wiremold, Lantech or — indeed, most Toyota suppliers? My hunch is that the answer to your question lies in understanding this difference. Many companies pursue a lean program, with lean officers training middle managers using lean tools and workshops to obtain improvements. But few senior execs commit personally to the lean journey so they never realize — in Art Byrne’s terms — that lean is the strategy.

Asparagus Is the Key

In the generation since so-called Japanese management erupted on the management scene with Deming’s 14 points, Richard Pascale’s The Art Of Japanese Management and William Ouchi’s theory Z in the early eighties, it has become generally accepted that any self-respecting company should have some sort of participative improvement effort based on team activities. And indeed, “lean” as a movement has fleshed out this intention by opening up a toolbox of specific improvement methods to carry this program out.

Pascale pointed out 30 years ago that, in the mind of the mainstream manager, running a company means (1) having a strategy, (2) setting up an organizational structure and (3) implementing the correct control and information systems. In my personal experience of companies, this is still an accurate description of managers’ mindsets.

Executives firmly believe that strategy, structure, and systems drive their financial results. Consequently, when the results are not satisfying they challenge their strategy (search for new juicy markets and abandon dried-out ones), they reorganize (cut the “dead-wood” costs) and they implement better systems (which IT has largely opened up by integrating reporting and scheduling on a vast scale). Executives growing up hearing about lean have now added a fourth lever: (4) an improvement program (lean, operational excellence, lean six sigma, world class excellence, production system, wear pink shirts and eat asparagus, etc.) to involve their employees in local improvements.

These improvement programs are expected to deliver savings to support the strategy and sustain the bottom-line, but are rarely strategic in themselves. The idea is that strategy, structure, and systems are the core elements but since reality fights back, the improvement program is needed to get people’s buy in and reduce the unfortunate financial side-effects of restructuring, reorganizing, and system changes.

The Real Key

When my father started learning from Toyota, first as Industrial VP and then CEO of a supplier, he had an epiphany: lean was the strategy, not a useful tool to clean-up the side effects of the existing strategy. In other words, Toyota made a basic, basic assumption which is so huge it’s hard to see

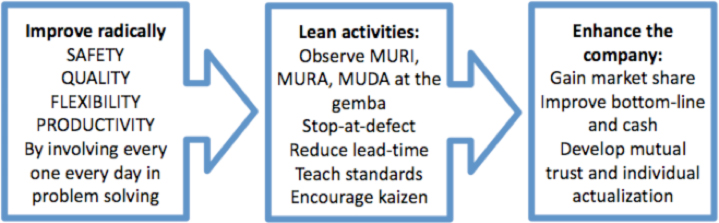

If you strive at improving SAFETY, QUALITY, FLEXIBILITY, PRODUCTIVITY by involving all people all the time in solving these sorts of problems, the resulting shape of your company will be more competitive, more profitable, and generally a more pleasant place to work.

This is a very strong assumption that involves a radical shift in focus for executives. In our recent study tour in Japan with a group of CEOs my father was always impatient about general discussions of how to do lean, what lean meant for the company and so on. He kept saying, reduce your accidents by half every year, customer complaints by half every year, your inventories by 20% and look for 15% productivity improvement, and strategy, structure and systems will emerge – they will become apparent.

If we take a step back, we see how much of a leap-of-faith assumption this can be to classically trained executives. Yet, this is precisely the insight others who have succeeded at transforming their businesses such as Art Byrne at Wiremold or John Toussaint at ThedaCare have had: improve value first, the rest will follow.

Lean in this sense can be defined by KAIZEN (improve safety, quality, flexibility and productivity) + RESPECT (do so by involving every one every day in solving problems together and deepening their technical skills). Precisely what Pascale had seen in the early eighties, balancing the strategy, structure and systems of western management with the staff, skills, style, and superordinate goals of “Japanese” management.

The answer to your question, is that after 30 years of hearing about participative employee-based improvements, most contemporary executives agree they need to complement their strategies, structures, and systems with some sort of improvement program, currently a “lean” one.

On the other hand, very few of them make the leap of faith to believe that their notions of strategy, structure, and systems will result from their drive to improve safety, quality, flexibility and productivity with their employees. Those who do so, and I know several, enter this very different room in which “lean” described by Jim and Dan in Lean Thinking – and have the corresponding results. They’ve learned to learn from lean. Learning from employee’s improvement initiative is, I believe, the heart of the lean transformation.