Four years ago, 50 bright-eyed wanna-be entrepreneurs sat in a room overlooking a deserted cobblestone sidewalk in New York’s Financial District. It was a Saturday afternoon and their minds were brimming with crazy ideas for new business ventures. They came to this business workshop expecting to build out their ideas. As they entertained all the possibilities, the workshop mentors started shouting, “Get out of the building!”

We wanted to force these wanna-be innovators to get out onto the street, interview strangers and validate demand. Did their big ideas solve for real customer problems? This was the first Lean Startup Machine workshop, and our goal was to teach entrepreneurs Lean Startup thinking in just three days. Eric Ries told us this wasn’t possible.

|

Today, we’ve taught the process to over 50,000 entrepreneurs around the world, entrepreneurs who have gone on to launch products and services that thrive on rapid cycles of experimentation. They’ve gone to implement Lean Startup thinking at their jobs and launch new products that thrive on rapid cycles of experimentation.

For my co-founders and I at Javelin, our question has been the same from the beginning. How do we turn people’s deeply-ingrained execution mindsets to ones that constantly question assumptions and explore possibilities in environments of rapid change and uncertainty? What’s the most effective way to do this? It’s a complete paradigm shift, but one we think is necessary for building 21st century businesses and solving 21st century problems.

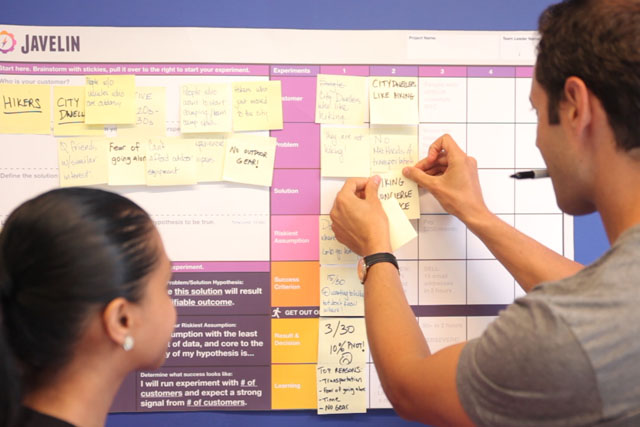

The tool that enables us to teach Lean Startup at scale is the Experiment Board. We’ve developed it through rounds of learning from the most successful entrepreneurs we’ve seen come out of Lean Startup Machine.

Effective Experiments are Hard to Design

Every experiment starts with a hypothesis. You want to test the validity of your assumptions. But few of us know how to formulate truly test-able hypotheses! Very few of us understand how to identify and test our really risky ideas and assumptions.

The Experiment Board is a tool we use to help others easily turn business, product, or feature ideas into experiments. We created it to eliminate (ok, minimize) the most common mistakes teams run into when conducting experiments for product and service validation. What the Experiment Board does is lay out the components of an effective experiment and help teams communicate and collaborate with their team members and stakeholders. Teams who use it gain alignment and make faster decisions as a result.

Common Challenges in Product Validation Experiments

Getting Buy-In

“Why do we have to validate this? We know people want this feature. Let’s just build it!”

Sound familiar? If your workplace culture discourages experimentation, the mere suggestion that your company validate the need for new products or features will prompt looks of horror from individuals in leadership positions. For people who are used to operating on gut instincts, the need to fact check their intuition is a barrier to getting buy-in. Especially as someone who’s been on the job for years, or even promoted for their intuition, it’s uncomfortable to have years of experience suddenly challenged. The know-it-all trap is easy to fall into, and it takes self-awareness to acknowledge that times have changed. What worked yesterday, does not work today.

One way to get buy-in is to provide your team members with what they need, but go ahead and still run the experiment on the side, showing them the results later. Involve one or two team members in designing your validation experiment so you have as much alignment as possible on what you’re actually testing, but run the test!

Structuring Effective Hypotheses

Once bought-in, many teams find themselves stumped as to how to actually structure their experiments.

To design an effective experiment, start with a hypothesis, a prediction for what you think will happen. (This can be phrased as a customer-problem hypothesis or a problem-solution hypothesis). The customer-problem hypothesis tests if your intended customer, or user, experiences the problem you think they have. The problem-solution tests if your proposed solution addresses that problem with a quantifiable outcome. Ideally, start with the customer-problem hypothesis, so you’re not assuming anything by jumping into the solution too soon.

Start by asking two questions: What problem does this solution solve and who has this problem? Identify who the customer or user of your proposed solution is. Next, brainstorm potential problems your customer could have that calls for your proposed solution. Make sure you timebox each brainstorm session and have each team member individually write on sticky notes to contribute. (This ensures that everyone’s opinions are heard and enables faster decision-making). Once you’ve selected your customer and problem to test, you’ve formed your hypothesis.

To define a problem-solution hypothesis, simply state that your solution will solve the problem for that specific customer. You’ll need to quantify the outcome you expect to see that will prove the problem is solved. (We’ll go over how to set a quantified outcome in a bit).

The right side of the Experiment Board tracks the progress of your experiments, so you can stick your hypothesis into the respective boxes to indicate the start of the experiment and keep everyone aligned and what you’re testing. This exercise is a collaborative and simple way to get your team engaged in running experiments.

Identifying the Biggest Risks in the Idea

After forming your hypothesis, it’s time to identify your riskiest assumption. This is where most teams get tripped up. Assumptions are beliefs that are core to the viability of your hypothesis. Think of assumptions as the behavior, mentality, or action, that needs to be true in order for the hypothesis to hold true. Your riskiest assumption is the one that is both core to the product or service’s viability and most unknown, meaning you have little data to prove it’s valid. When you’re testing a customer-problem hypothesis, your riskiest assumption is one that supports the belief that your customer has that problem. In a problem-solution hypothesis, the riskiest assumption is if it’s the right solution to solve the problem. It’s important to always test your riskiest assumption first.

On the Experiment Board, brainstorm all the possible assumptions you’ll want to test, then identify the riskiest assumption to test. Involve everyone on your team (and a few people who are totally unfamiliar with your project) in brainstorming assumptions. Why include “strangers” in your project? These people are less prone to what we call confirmation bias. If you’re intimately involved with the project, there’s no way around this.

Once you have a few assumptions, ask your team members to dot vote on post-its to select the assumption they think is the riskiest to test. Your experiment will test if the riskiest assumption is valid or invalid. If it’s valid, then your hypothesis holds true. If it’s invalid, you’ll need to change your strategy by changing one or both elements in your hypothesis. This is called a pivot. The goal is to get closer and closer to something that holds true. The Experiment Board helps you track pivots, which communicates your validated learning and progress to stakeholders over time.

Staying Accountable to the Results

Defining what success should look like is the most crucial step before conducting an experiment. Many teams want to just build and see what happens. The problem is, without setting a success criterion, all the positive results you see will look like validation. After spending six months on a project, what does one paying customer really tell you? Is it really worth your time to allocate more resources and keep building? Or is there not enough interest to spend more money on it? The results you see after running an experiment are subjective. You might think you have enough validation to put more budget behind it, and another person will disagree.

The minimum success criterion is the weakest outcome you expect to see in order to take on more risk and continue. Without defining success up front, teams will argue over whether an experiment was successful or not; it is impossible to interpret the results of the experiment without succumbing to some form of bias. Make your experiments measurable!

Running Quick, Iterative experiments

A common misconception is that the only way to test an idea is by building it so customers have something to interact with. But there are many, surprisingly counterintuitive ways to test customer demand without building anything. The most insightful, low-cost ways include conducting interviews, setting up a landing page test, or delivering the service manually (aka concierge). The technique you choose depends on the assumption you’re testing, the time you have, and how much certainty you have about the direction you’re going in. These quick, low-cost ways to test your assumption will reduce the time it takes to get customer feedback.

How We Validated the Need for the Experiment Board

|

Our hypothesis in designing the Experiment Board was that by increasing the speed at which teams can set up and conduct experiments, the sooner they would discover viable ideas for products and services people will use and buy.

Before we created the Experiment Board, we found that teams too often spun their wheels, argued indecisively, and wasted time struggling to understand what and how to test. When we tested the Experiment Board tool in our workshops, teams began running their first experiments within 10 minutes. Simple things like using stickies and timeboxing enabled communication, alignment, and faster decision-making. The flow of the board design gave teams a tangible sense that they were making progress.

Many teams often discover that their customers didn’t experience the problem badly enough to use or pay for a solution. They often abandon their ideas completely after three pivots in favor of an actual problem they find during their fourth round of experimentation. The most successful teams often pivoted multiple times until they found a key insight leading them to a bigger opportunity. This all takes place within 24 hours of designing and running experiments with actual people! Crazy, right? But it works.

Today, our tool enables us to scale Lean Startup education to 400 cities around the world so any entrepreneur or corporate team, however new they are to the scientific method, can start running experiments. I hope you can use the tool in your workplace to build products people want, in less time.

For more about the nuances in designing experiments watch my video tutorial here. In my next post, I’ll talk about the unique challenges intrapreneurs, innovation teams, and change agents within large organizations face when running experiments and using Lean Startup techniques, and how to structure an environment that enables rapid experimentation and pivoting.