In our new Digital era, some dream of people-free production lines. First because machines are expected to do repetitive and complex tasks in a more reliable and predictable way than human beings. And second, less often openly admitted, because it may be a chance to move out of critical activities the costly, occasionally procrastinating humans, who demand rest, recognition, rights and a fair share of the profits. But the assumption that people-free plants or services would fare better is totally overlooking what humans bring into the operation: thinking, and particularly lean thinking!

We (Lean Sensei Women) are a group of women from different continents, horizons, and professions who share a commitment to the development of people, respectful of both teams and environment, with a view to produce more value for customers and to society. This article reveals why we believe that people-free services and plant floors prevent meaningful learning from happening, and why digital systems will always require people and the capacity for human learning.

Underlying this discussion is a belief that kaizen and a focus on understanding purpose–the “why” of the work–is key, argues Catherine Chabiron. Jean Cunningham builds on this point by pointing out that the question is not whether we have to choose between Lean thinking OR technology; that both Technology or Digital offer great opportunities to enhance work conditions and respect for people.

Wrong decisions or investments on technology can also take us along the wrong path, warns Cécile Roche. She points to chatboxes or phone robots that fail to deliver, to ERPs making decisions for you, and CAD design that decreases our actual knowledge of how things work. Not to mention the risk of automating poor processes, a sure way to set muda in stone. That point is borne out in Anne Lise Seltzer’s story of a live example of loss of professional knowledge in services, as a result of automation.

Core principles of Lean can certainly pave the way to digital, argues Lucy Liu, who takes us through the journey of Toyota and what those engaged in Industry 4.0 could learn from it. Sandrine Olivencia recounts a disastrous bank wiring experience that suggests how key Toyota Production Systems concepts could help find the right balance between automation and human added value.

Above all, Lean thinkers should not fear the Fourth Industrial Revolution, concludes Rose Heathcote, who proposes a way to prepare for and live in the digital era. Learning with problem-solving and Kaizen, seeing and optimizing as a team through gembas are a sure way to avoid useless investments, failing products and painful flawed assumptions.

****************

Catherine Chabiron

Catherine Chabiron

Remember that only humans can investigate, and learn from the 5 whys.

In The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect, author Judea Pearl (who has been at the heart of a revolution in artificial intelligence and computer science) suggests that the key difference between humans and robots can be found through the ladder of causation (in other words, the different maturity levels of understanding causes). Present day learning machines, he says, are no more advanced than most animals. Granted, they have much greater computing capabilities than us, humans, but their thinking and learning is limited, as for most animals, to associations : “if I see this, it tells me that”. Early human tool users, he contends, were on the second rung of the ladder of causation if they acted by planning (“what happens if I do this ?”) and not merely by imitation. This is also how babies learn the effects of their acts and acquire much of their causal knowledge. The highest rung of causation on the ladder is held by modern mature humans, who can imagine worlds that do not exist; and think retrospectively in terms of “what if I had done this rather than that, what would have happened then?“; or “why did it happen ?”

Humans are needed in all the factories, in all the services of the world because they are the only ones who can investigate with, and learn from, the 5 whys. Automated chatboxes on websites can take you through the most frequently asked questions, but, when you receive a box of chocolates instead of your order of soap, only humans can investigate the problem and solve it. Amazon massively invests in good-picking automation or packing facilities, and they also extensively apply Jidoka in customer services, as they wisely accept that the best way to address errors at delivery is a swift reaction, a temporary freeze of the sale on site and effective human problem solving on site to prevent re-occurrence (see Marc Onetto discuss this interviews in Planet Lean and the McKinsey Quarterly).

Machines help us to expand our capacity to re-combine existing knowledge forever (this is no longer a fiction in music or painting, by the way). We may even see machines learn their way up the ladder, while we placidly rely on them. But mastery over machines and their underlying principles is key. Continuous investigation on the why, and persistent kaizen, must remain our human prerogative.

****************

Jean Cunningham

Jean Cunningham

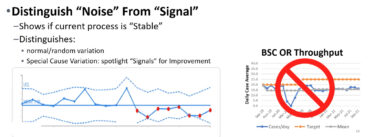

As we integrate more technology into the work, how will we think of waste?

Technology marches on. And it always has. We will not hold it back. The question is “how will we think of waste as we integrate more and more technology into the work?” For instance, we used to manually enter material receipts into the system, and then manually view and check them against a Purchase Order. Manually review and match to the invoice, and manually change the status in the system that it is ready to pay. And, when I was CFO at a medium size company, I actually physically signed the checks. (It was so repetitive that I actually ended up with a little shoulder injury!) This process was drudgery, repetitive, and mind numbing. Especially when there was technology to auto-match, and kick out the exceptions for review. Technology can really be a way to respect people.

But there is still meaningful work to be done using our creativity and genius in this process. Pursuing perfection for example. Not just fixing the deviations, patching them up and calling that work. No, the real work is understanding what is source of the deviations, getting to root cause and finding creative poke yoke or mistake proofing to reduce forever the rework and rejects.

The question is not: “are robotics, block chain, electronic eyes, and more, bad or anti lean?” They are inevitable and useful in our quest to reduce waste, to make work simpler, easier and faster, and release our human capacity for genius to work on true value add activity.

****************

Cécile Roche

Empathy, relationships, and emotion are human qualities that will always be essential to understand what our customers truly value.

Many people think that Lean and Digital are complementary. “Before digitizing a process, it must be optimized. Otherwise, we automate waste”. That’s true, of course. But that’s not enough, far from it. This would imply that we can imagine an ideal company, then automate it…ignoring the fact that we know an optimized status does not remain so for long. The next day, something happens that makes the model not so perfect. I see it every time I’m on the Gemba. And it is at this point that the role of human beings becomes fundamental.

How many of you have been frustrated by those phone robots that ask you to type 1, or 2, or 3… but never propose the option you need ?

How many factories have implemented a “perfect” (and very expensive) ERP system to do everything (at least according to the IT department…) while every day, we hear operators saying “No! We can’t do this, the ERP won’t allow it”. A recurrent question I have for top managers, when we are together on the floor, is to ask: “who is the factory boss, the ERP or you?”.

Ever had to challenge your child’s homework when she computed a 300-litre car tank capacity to ensure a drive of 600 km? And the same children, who grow up to be engineers, continue to expect systems to give several decimal precision results, without a clue as to the system’s underlying general principles. They continue to entrust the computer with the task of making high-tech products without understanding what really matters to customers. We see that every day in engineering teams.

Empathy, relationship, emotion are human; these qualities are essential to understand what makes our products valuable to customers. Information is data that allows a decision to be made (in a given context). But information will only become knowledge if it is processed by a human brain. A lot of data is available to everyone, but to be able to turn it into a competitive advantage, you have to be able to observe, understand and talk to your customers. Machines increase our power to act, and our power to think. They also increase our accuracy. But to be approximately right will always be better than being very precisely wrong, and the critical mind of the human being must help us to understand the orders of magnitude, the use cases and the context elements. And these will make the difference on our products.

****************

Anne Lise Seltzer

Replacing certain key human interactions with a machine interface can produce waste and ultimately destroy valuable business.

The installation of machines in the relationship between a “customer” and a “supplier” can have serious consequences, in particular on the ability of companies to produce the service expected by their customers. I encountered an illustration of this in a temporary employment firm, where I was helping the teams solve the problem of efficiently matching candidates to serve their clients’ orders.

In recent years, the process of bringing temporary candidates into contact with the agencies has been digitized. Where previously the applicant used to register with an agency and was interviewed by a consultant, today she must register online without going through the agency. It is therefore her responsibility to provide data on her skills and research. Applicants are left to guess what is the best way to do this, and their forms are very often incomplete. Unfortunately, it is this information that will be used by consultants when they receive an order, to do the matching.

This loss of knowledge and know-how, resulting from the way applicants enter into contact with the agency, directly reduces the agency’s chances of identifying potential candidates for assignments, even though the main challenge (and potential competitive advantage) today is to find temporary staff for their customers right first time and on time.

In the interim business, the initial interview was a “key step” in creating value for the agency’s clients. Putting a machine interface to replace this key action of the consultant therefore directly affects the ability of teams to build knowledge that is strategic for the success of the activity.

This machine interface, which was intended to save teams time and productivity, ultimately has the opposite effect. It is a source of waste, team exhaustion, dissatisfaction of customers and temporary workers and potential loss of business for the company.

****************

Lucy Liu

Toyota’s success reminds us that developing people must remain a priority at all times.

I have worked with Toyota for almost 29 years, and experienced how technology advancement has enabled the business and people to achieve better safety, quality, delivery and cost effectiveness. During all those changes, developing people and building a learning organization has been the main focus. Toyota has demonstrated its ultimate respect for people and never-ending effort on pursuing continuous improvement and innovation through building problem-solving capability. Hence, Toyota has been able to use less time, less resources and less investment in capital, while achieving much more than its competitors.

I have also observed and worked with companies who are chasing ”Industry 4.0” as their goal, without building and sustaining a strong Lean foundation. The result is that they are not able to achieve return on investment. Very expensive automated machines/systems could only deliver 50 to 60% efficiency. There are a number of problems I have identified: (1) Lack of focus on skill development. When highly complex equipment breaks down, people struggle to fix the problem quickly and effectively as their key effort is on selecting and installing the machine. (2) Lack of involvement of gemba people in designing the automated operations/processes, resulting in failures to achieve the desired outcomes; (3) Lack of effort on building problem-solving capability and engaging people. Even with massive amounts of data being collected, but not being utilized.(4) The Lean management concept of standardization and visualization is not created, or hidden in the computer. If the computer is shut down, no one knows where to find the information.

There is no doubt that the speed of automation and digitization advancement would exceed the imagination of many. We must embrace the digital era and accept the challenges. Toyota’s approach to this transformation could be summarised by Toyota VP Mitsuru Kawai: Automation is to materialize craftsmanship and make it standard. Afterwards, we can apply the standards to effective automation. Once we built automated lines, we can’t make the next step of improvement if we don’t continuously develop people. Therefore, developing people is a necessity at all times! Toyota’s practice is to think who can do the job first, not what to use to make the product.

Hence, the above issues could be addressed by applying the lean fundamental principles such as standardization, people development and problem solving. By doing so, we could avoid much waste in capital investment, down time and human resources. If a company only focuses on machines, not people, they will not maximise continuous improvement.

****************

Sandrine Olivencia

Automation only makes sense if it improves the life of human beings; when technology creates new problems, it defeats its own purpose.

Last Saturday, I had to wire money. The bank’s website would not let me add a new recipient, because the phone number listed on my account was incorrect. To change my phone number, I had to request a new security code, which would be sent to me by post within 5 to 7 days. At first, I thought: “What’s the point of doing this online if I have to wait 7 days for a security code?” So I worked up some courage and decided to make the transaction in person at my local agency, something I hadn’t done in a long time.

What should have been a simple trip to the bank turned into a nightmare. There was only one person at the counter, so I waited in a long line for more than 25 minutes before she finally called my number. I then spent another 45 minutes watching her struggle to perform the wire transfer: the application on her computer displayed an error every time she hit the “complete” button, and she had to re-enter all the information with each attempt. She called IT support, but was put on hold after listening and “speaking” to a robot and never got to talk with a person. She then tried to call two colleagues, but neither one picked up their phone. Meanwhile, she was keeping an eye on her screen, watching the progress bar move very slowly, crossing her fingers that the wire transfer would finally go through.

I felt terrible for her. Pearls of sweat started forming on her forehead from the stress. She kept glancing at the growing line of people, unable to think of a solution. After four unsuccessful attempts, I asked her to call the manager to help her out of her misery–but of course, he was off work on Saturday. When the substitute manager finally showed up, my patience had run out. I blurted out that he didn’t respect his clients or his employees. It took some effort (and a bit of yelling) before a couple of agents finally left their comfortable offices to help deal with the line of customers. After two hours, I finally left the bank…without my wire transfer completed. As I left, I noticed a paper board at the entrance of the bank inviting customers to a demo of their new online system, to be released soon!

This example illustrates how “machines” can turn humans into their servants when they don’t work as expected or require too much manual handling. This is completely contrary to the lean principle of Jidoka, or “separating machine work from human work,” which implies making machines (or systems) as autonomous as possible so they require little supervision or tending from humans. The basic assumption is that automation, whether using physical machines or digital tools, only makes sense if it improves the life of human beings by reducing burden and/or improving quality and speed. When technology creates a whole new set of problems, or requires extra work from people to keep running, it defeats its original purpose.

Jidoka is also based on the principle of “respect for people,” which means creating a safe environment in which workers can thrive and innovate. The success of a company relies on the success of every employee, so it would be a shame not to take advantage of what technology has to offer. But we have to ensure that new technology is adopted only when it’s really useful, and also make it as autonomous as possible. Kaizen led by the people themselves is a great driver for making this happen.

****************

Rose Heathcote

If we stay close to the customer and the actual work that delivers that value as tech advances, then we will continue to learn and adapt.

What does it take to keep on learning? A generous dose of failure and a healthy appetite for risk.

My generation was taught not to fail. Failure is bad. Avoid risk. Right first time! This stifling upbringing slows down innovation and reduces the confidence to try new things. I guess machines don’t have this hindrance.

To learn we should be prepared to fail. I must add (upbringing kicking in) that not with catastrophic results, where lives or customers are severely affected, but the kind of failure where we are open to experimentation, learning and adjustment. Where we protect people by taking the time to frame problems and guide thinkers down the learning path. In this way, we create opportunities to grow from new theories, ideas and ways of solving problems.

So, what then if we became people-free? For Africa, this still feels a long way off, but it’s still very much a part of the conversation at dinner parties. We ponder the evolution of tech and automation of repetitive tasks. We note the impact on people, what jobs they perform and how schools need to evolve. We see smart factories replace roles requiring repetitive and fatiguing activities. We observe machine learning producing information at the speed of light (but someone still needs to base decisions on it). We note the bank teller role has vanished and is replaced by a personable, friendly ‘insurance sales person’ with fancy tech and attractive décor to enable shorter cycles of customer value delivery. So, there are still people somewhere overseeing something. The workers haven’t disappeared altogether – they are just taking on new skills and responsibilities. The human work is re-aligning to survive alongside the non-human work.

And things do still go wrong in this world, which means the learning isn’t dead – it may look a little different, but there is something still familiar here.

The 4th Industrial Revolution is not to be feared. Tech progress has the potential to catapult performance, protect companies from extinction, and help them thrive in a tough, competitive future. If we stay close to the customer and what brings them value to survive – stay close to the actual work that delivers that value, and not fall prey to cemented-in processes, then we will continue to learn and adapt. We’re still in the driver’s seat albeit, down a different, digitised road.

AUTHOR BIO: LEAN SENSEI WOMEN

Coming from different continents, horizons and professions, the individuals who form Lean Sensei Women are all recognized lean Senseis, who help companies and organizations build sustainable growth through lean management. They believe in the development of people, respectful of both teams and environment, with a view to produce more value for customers and to society.

Catherine Chabiron: Board Member, Institut Lean France. Author of Notes from the Gemba in Planet Lean and executive lean coach.

Jean Cunningham: Jean Cunningham, a former CFO and LEI board member, is widely recognized for her pioneering work in lean business management systems and the lean office. Her books include Real Numbers, The Value Add Accountant, and Easier, Simpler, Faster.

Rose Heathcote: CEO, Lean Institute Africa. She is the author of Clear Direction and Making a Difference.

Lucy Liu: Currently the Head of Supply Chain Academy for Asahi Beverages, Australia and New Zealand. Over a 28-year stint with Toyota starting at the shop floor, she progressed to management roles include Australia TPS Office and Capability Development Department Manager.

Sandrine Olivencia: Lean sensei and member of Institut Lean France. Specialist in Obeya and product development expert for the digital world.

Cécile Roche: Lean sensei, member of the Institut Lean France, Lean Director of the Thales Group, and author of several books, in particular on Lean in Engineering.

Anne Lise Seltzer: Member of Institut Lean France. Lean Coach in Services and Support functions. Trainer for Lean & Learn at SOL France (learning organization).