Our business magazines are full of studies explaining how our skills need to change to absorb the changing technologies (automation and AI) but also to adapt to our fast-changing world (empathy, communication, entrepreneurship, initiative, agility …). And those studies are right, we need to change!

That said, change…how? A better approach could come to powerful common sense such as treating employees like adults, building great teams, and ensuring that every employee deeply understands the company and what it does, says former Netflix Chief Talent Officer Patty McCord in this excellent Ted Talk. Change also relates to the nature of how people work and think together—calling to mind a study in the US led by the Pew Research Center which notes that women executives are perceived to do a far better job than men at creating a safe and respectful workplace or considering the societal impact of business decisions.

We believe that Lean, which has proven itself to be a clear, demonstrated, option to survive and expand in a globalized world, offers help in framing a path forward. Lean repeatedly pushes us to develop new competencies (or recover lost know-hows) through kaizen and problem solving. And Lean requires a major shift in our behaviours. The following commentaries look at this issue from a variety of perspectives.

Consistent Lean behavior from top leadership sends strong messages and prompts tangible changes in organizational culture, says Lucy Liu in her personal account. She shares how Toyota leads their workforce through small behavioral changes that become the base of a new culture—and of new knowledge. Such changes can take place in any type of organization, explains Sandrine Olivencia, who shares insights on how the Toyota Way can change things dramatically in a digital company, noting that a lean transformation is first and foremost a personal, cognitive transformation.

Lean provides a framework for processing information into working knowledge, says Cécile Roche, who shares ways that managers can help (and even harm) learning by their teams. (Hint: pugnacity and humility help.) And Rose Heathcote shares three lessons on how to do Lean with people, and not to do Lean to people; one key is to “show you care by practicing what you preach.”

Lean help teams see their work with a changed perspective, says Anne-Lise Seltzer, sharing a story where Lean practice revealed grounded, specific insights that helped improve work by experimenting with small steps on an existing practice. Such an approach rests on a foundation of open-minded acceptance of seeking new understanding of the current situation. In that regard, a Lean approach can dramatically challenge conventional wisdom about how to manage and lead any organization. For example, Jean Cunningham reminds us that if we, as managers measure our own success based on who or how many work for us, then we hold back the growth and development not just of the people, but of the overall organization.

So how do we proceed? Start with regular visits to the gemba, advises Catherine Chabiron, who summarizes all the above contributions in what top management needs to change in their behaviors, noting that, “Lean starts with understanding the current situation.”

****************

Lucy Liu

Lucy Liu

Lean is not about theoretical research but about practicing respect for people and continuous improvement on gemba every day, with everyone and in every situation.

Lean is not about doing a theoretical research or writing a paper on top of another paper to accumulate new knowledge. It is about practicing respect for people and continuous improvement on gemba every day, with everyone and in every situation. It is a process of changing behavior through improving the way we do things.

Thirty years ago, I started my career with Toyota Australia as a shop-floor team member. This was truly a multi-cultural organisation with more than 100 nationalities (ethnic backgrounds) working under the same roof. Many team members had limited English. Industrial actions often occurred due to the confrontation between management and the union. At one point in time I was elected to be the union representative and, one of the outcomes led to a five-day strike.

So, how did Toyota Australia manage to become a highly rated and respected plant over time (although the Toyota Australia Manufacturing operation ceased in Oct 2017 due to the exit of the whole Automotive Industry from Australia)? How did I grow within the company and change from being anti-TPS to taking the role of managing the TPS Office for eight years?

In the 1990s, the 5S at Toyota Australia was very poor. Our Japanese EVP for Manufacturing, Sekiya-san, was an outstanding TPS sensei. One of his most remembered actions was not picking up rubbish from the shop floor, but have his wife join him on weekends to do so. This sent a strong message to all managers, who started to do the same. This consistent behavior contributed to a significant levelling-up of 5S, which is fundamental and important in building the TPS/Lean foundation.

Another example is that the Manufacturing Directors had daily, weekly, and monthly activities scheduled to observe standardized work, and to identify abnormalities and Kaizen points together with the supervisors and team leaders. They listened to and coached these gemba people on the importance of standardized work and problem-solving through participation and respectful behaviors. This practice became the leaders’ standardized work over almost 10 years before the plant closure, and helped the plant achieve the Toyota Australia’s mission of “Last Car, the Global Best Car”, when the vehicle was sent to the Toyota museum in Japan.

I mentioned earlier that I transformed from an anti-TPS person to leading the TPS Office and promoting TPS in the Lean Community. Here’s a bit of background regarding that. Toyota always has believed in its people’s ability to learn and grow. Hence, developing leaders from within was a priority. I benefited in my early days of the opportunity to participate in TPS training, in QCC, working in Japan to learn how standardized work and kaizen was done and how supervisors manage abnormality. And later, leading cultural change projects, working in global assignments and heading the TPS office in Australia. This journey was truly an action learning process. I learned from observing the actions/behaviors of the Toyota leaders, the TPS Sensei and shopfloor people. Their involvement and ownership, as well as seeing the results of the problem-solving results, influenced my thinking and changed the way I do things. By doing different roles, I gained new insights and developed new knowledge, which continues to shape my behavior.

The above are just a few examples to articulate two key arguments: (1) The consistent behaviors of the leaders could lead to changes in organizational culture (organizational behavior) as they send a strong message to people about what is important and expected; (2) Employees’ mindset and behaviors could change if the organization focuses on nurturing people and giving them the opportunity to learn, participate, and lead (like me, one of many who have benefited from Toyota’s practice). My one-point lesson is that TPS is about accumulating small improvements every day from everyone. These consolidated small behavioral changes eventually become the base of the lean culture and new knowledge.

Lean is a journey of action learning. It requires behavioral change from the top to every level of the organisation. If there is no behavior change, then there will be no improvement in practice. So, certainly, lean is more about changing behaviours, not just accumulating new knowledge.

****************

Sandrine Olivencia

Sandrine Olivencia

A Lean transformation is first and foremost a personal, cognitive transformation.

Every year, a small army of “Lean” management consultants launch operational excellence programs, which generate quick results but create no lasting change. They pick a few processes to optimize, and then reduce costs by forcing teams to adopt TPS tools and practices. In such an environment, it is impossible to engage people in continuous improvement. When the consultants leave, people gradually return to their old habits, with a bitter taste in their mouths and even more mistrust towards management…and towards Lean.

It is tempting to believe that simply applying (and often distorting) Lean tools to fit the current situation is enough to bring lasting change. But this is like changing the cover of a book, and hoping that the story will change. Lasting change only happens if we see the exercises as an opportunity to modify the way we view our situation, think about our own work, and act to resolve problems.

This first misconception breeds the second: if Lean transformation is just a matter of performing some exercises, then why not delegate? Because if a Lean transformation is to succeed, the leader needs to change her way of thinking and acting first, so that she can help her collaborators do the same. This is in line with Toyota’s management approach called the Toyota Way. Its two pillars, “continuous improvement” and “respect for people”, embody Toyota’s values and ways of working. Continuous improvement means the need for everyone in the organization to challenge their own beliefs, incessantly look for small improvements that can benefit the business, and always check the facts on the gemba before acting. Respect for people means the need to take everyone’s problems seriously because everyone deserves to succeed, and to develop teamwork and mutual trust across the organization.

The day John, the CEO of a UK-based digital firm, understood that Lean started with him, things began to change in his company. For months he tried to convince his teams to track KPIs, write problems on white boards, and use new tools to improve processes. But his efforts just bred frustration and tension. I was taking him to the gemba, but between visits he went back to his old habits. I finally asked him to spend 15 minutes every day on the gemba, just trying to understand one specific problem without proposing a solution. After a few weeks, John told me “I think I finally understand what you mean by facts over data!”. At that moment, he stopped focusing on KPIs and started helping his teams resolve specific problems that were limiting success. John’s new behavior slowly but surely transformed the atmosphere in the company. During my last visit, the creative energy was palpable: people were excited to talk about their kaizen, share their innovative ideas and collaborate with their colleagues.

A Lean transformation is first and foremost a personal, cognitive transformation. The reason why so many Lean journeys fall short is because this fact is not understood. Also, it’s hard! It takes a lot of courage to admit that we were wrong about something. It is hard to change the way we manage, to consciously look for problems instead of making them disappear, and to ask questions to develop people instead of giving them instructions to follow. After two years of practicing Lean thinking with her teams, I asked the Digital VP of a US non-profit organization what she got out of it. She answered: “I have learned to be comfortable with being uncomfortable”. You know someone has made the switch to “real” Lean thinking when they tell you how deeply it has changed them.

****************

Cécile Roche

Cécile Roche

In real life, we have to re-invent answers to each new question, and learn to ask the right questions–most of which will be difficult to answer simply.

Those who are familiar with Lean understand that Muda qualifies as waste. While the waste hunting is in full swing in many teams, managers are often surprised when the results prove to be not really sustainable. This is probably because it is not easy to admit that these wastes are essentially due to our poor ways of working. I have in mind some recent examples.

The first is a typical case of what we call a “pet design”, in which the architecture of a product is chosen not for its relevance or efficiency, but because it is the configuration that the engineer masters best. Of course, that costs significant rework, additional costs and delays. Under time pressure, the unconscious choice will be to avoid the unknown and use the existing knowledge, without taking the time to ensure that this choice really meets the customer’s constraints. Why? Because a set of accepted behaviors generates this fear of taking risks.

The dream of some managers sometimes turns into a bureaucratic nightmare. One of my bosses, during a work meeting with engineering managers, recognized and praised a good practice observed in a project, one that demonstrated an excellent initiative mindset. A while later, during a trip to another place, he was surprised to find that this initiative had been the subject of a mandatory procedure: his recommendation was perceived as a prescription. Obviously, this idea did not have the same interest in a different context. That’s how a good initiative becomes a rule… that kills the initiative. Why? Because it is easier to apply a generic solution than it is to ask questions.

We often prefer answers to questions, solutions to problems. We think that a lot of knowledge will give us all a catalog of solutions. But in real life, we have to re-invent answers to each new question, and learn to ask the right questions, most of which will be difficult to answer simply.

This is why I believe Lean is more than just accumulating knowledge: it’s about challenging our own behaviors.

An engineering team I know in Asia had a high turnover, as young engineers sought to increase their salaries by changing companies very quickly, in a favorable labour market. The manager decided to change the way he worked, to develop autonomy. He established pull systems that allow everyone to understand how their work creates value and spend much more time supporting the teams than controlling them. The turnover rate fell from nearly 30% to less than 4%, while compliance with commitments has become the norm.

Another case is that of an industrial manager, who after years of being convinced that he was a real Lean manager, undertook to seek assistance from a Sensei and declared after a few months that he was relearning everything from scratch. Rather than seeing Lean as a succession of action plans that he made others do, he began to conceive takt time as a learning dynamic—one that he first applied to himself, with impressive results, on both operational performance and on the team’s commitment level.

What is fascinating in both examples is the influence the behavior of a single manager has over a large number of people. Starting with yourself with pugnacity and humility has a disproportionate effect.

Knowledge is important, but doesn’t exist outside of our brains; it is just information. You can’t accumulate knowledge for others, but you can help them transform the information they have (data, context, facts) into knowledge (decision-making skills, hindsight, critical thinking) by changing your own behaviors: ask questions and don’t give answers, improve yourself, show the direction and let people find the way.

****************

Rose Heathcote

Rose Heathcote

When you do Lean to people, you turn them off faster than you can say “change”.

I was 19, a fresh-off-the-press Industrial Engineer looking to make her mark in the world. Handed the opportunity to redesign operational areas in our local carrier, South African Airways. With budget in hand and enough free reign, I kicked off in the area where they pack the duty-free trolleys. Sweet! I had accumulated a mountain of knowledge on how to redesign anything through my studies. I was so ready for this. Full of confidence…wet behind the ears. I created what I thought was the optimal design, using cracking tools, that was surely the best way in which to receive, process and dispatch duty-free trolleys for each flight. It was perfect and ready for implementation…but oops…I was the only one who thought so. The affected team took one look at the proposal and dug their heels in.

Lesson #1: It doesn’t matter what you think you know, when you do Lean to people you turn them off faster than you can say “change”.

As we bump ours heads, we evolve. This experience taught me that no amount of knowledge can make things change. It’s putting yourself in the shoes of others that means something. When you do this, you naturally change your behavior in how you offer your support.

In my role, I’ve realized that before I can expect any change from my own team, or any change in how we bring value to our customers, I have to take a hard look at myself and how I do things. Introspection and self-reflection is no easy task – it gets personal. But it goes a long way in showing others how serious you are.

Lesson #2: Be brave, look inward, adjust and show your team what is possible.

As leaders (and humans) we don’t always get it right, but I’ve seen some of the best Lean Transformations take place when the leader interrogates his or her own behavior. This is the work that makes the change stick. It means being willing to open yourself up to new experiences, realizing that you don’t have all the answers, and consistently guiding your team in the right direction. How? Well, you’ll need to figure out what activities will help you drive the right behaviors for you. But for me it’s about:

- Taking the time to provide clarity to my team on where we are going, why and how.

- Spending time at the Gemba, listening, asking questions, learning and offering support.

- Following my own purpose-built standard work, so that I get the right things done, every day and not fall prey to chaos.

- Engaging slow thinking myself, as a means of setting the scene for others on how to go about tackling problems.

- Practicing what I expect from others as best as I can, consistently.

Lesson #3: Show you care by practicing what you preach.

****************

Anne Lise Seltzer

Anne Lise Seltzer

Lean is not about teaching people what they need to know about their job in theory. It is an action learning system to “learn to learn” the key knowledge necessary for the work.

When a firm engages in a lean approach, it is common to hear such reactions as, “We are already experts in our job, we don’t need externals to tell us how to work!”.

I heard this and other such reactions from the staff of an accounting team I was helping. I had less knowledge in this field than they did, and at the beginning it was very difficult for them to imagine what value could be achieved with lean in their daily work.

And that’s where we get to the heart of our subject. Yes, the lean approach will allow teams to strengthen their knowledge in their field of activity, but it will not be just any kind of knowledge, and above all, their learning will be the direct result of adopting new attitudes in the way they work together.

In concrete terms, lean helps teams wear new glasses to look at their activity with a changed perspective, and imagine alternative ways of doing things, using existing lean methods and tools. As they experiment and see the effect of it, they learn. The trick is not to make a radical change, but rather small steps on an existing practice. Very often it will start with experimenting with a different attitude.

For example, as soon as a problem arose, the accounting manager started asking her employees questions rather than providing answers. As she practiced this new approach, she was amazed to see a young woman, rather discreet in general, grab a subject on such a query and, in the purest Sherlock Holmes scientific mode, embark on an analysis of the situation and the search for root causes. Thanks to the change in her manager’s attitude, a new space for reflection and action had been opened up for her, unveiling the right to go and seek answers and make concrete proposals to improve the situation. In doing so, this young woman deepened her knowledge of the subject related to the problem and made a useful, contextual learning, the opposite of a theoretical one.

The accounting team also changed its attitude: rather than passively continue to receive late key information at the close of each month, from another department, they allowed themselves to go and amiably inquire…only to find out that nobody in that department knew the precise deadline for the monthly data. None, in addition, had any clues how late information could impact the accounting department.

Lean is not about teaching people what they need to know about their job in theory. It is an action learning system to “learn to learn” the key knowledge necessary for the actual work. This requires the implementation of new attitudes that create the managerial conditions necessary to deepen the understanding of the real situations, clarify the needs of the actors and experiment with new ways of doing things, both internally and with customers or suppliers. The adoption of these new attitudes not only leads to better performance but also to a more sustained commitment over time by the teams.

One of the things that touched me the most with this accounting team was when someone came to me after a few problem-solving sessions and said, “I never thought I’d learn so much about my job when we started lean!”

****************

Jean Cunningham

Jean Cunningham

Get close to the work–not just as managers, but in ensuring that all the people have the ability to get close to the work in new ways.

One of the most exciting aspects of lean culture is the tearing apart of functional boundaries and focusing effort on customer needs that cut across the organization. But maybe not for the reason I initially thought. To do this type of work, we have to work together across these internal boundaries, which often feel like internal barriers. We join together, cross functionally, to look closely at a process to see how it works. And as we do this work together, we begin, together, to see the work in a new way. We also get to see each other in new ways. Not as functional chest beaters, but as people struggling with poor processes. And we can see that not only was our own work difficult because of delays and rework, but also that everyone’s work was difficult because of delays and rework. These straight lines on the organizational chart begin to be irrelevant to the work, and we are able to focus person to person.

Through these developing personal relationships, we are drawn into the work of others, and learning ourselves. Gaining new skills, gaining new perspectives.

Before long people are ready to move to newly defined roles and activities based on the work and not on an organization chart. The work of management is then to be able to create an emotionally and intellectually safe environment for people to move and use the new capabilities in new ways. In new roles, in new teams, in a new organization system.

If we as managers measure our own success based on who or how many work for us, then we hold back the growth and development of not just the people, but of the overall organization. And when we hold tight to our personal organization status, then we limit our own growth, as well. As our other contributors have noted, it is about getting close to the work in new ways. But it is equally important to ensure all the people in our organizations have the ability to get close to the work in new ways. This type of support and leadership creates new insights, deepening understanding, and creating new leaders throughout the organization. This is the work that really never ends and keeps on returning real value.

****************

Catherine Chabiron

Lean starts with understanding the current situation.

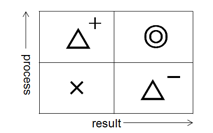

Isao Yoshino, who worked 40 years in Toyota, gave us some input in 2018 on how Toyota manages and based much of the discussion on this diagram:

A sophisticated process can indeed produce poor results, while great results can be achieved through sheer luck. If you want predictability and repeatability, if you are serious about what you want to achieve for your company in the long run, you will need to work on the method.

Lean starts with understanding the current situation. This is the purpose of visual management, obeyas and gemba walks; anyone who is even mildly interested in Lean management knows this by now. But the hard part is to face the problems you unveil. And some of those stem from bad decisions taken at the top, like pushing for big batches, to pay off large, expensive machines, or launching sales campaigns that trigger huge, unplanned variabilities in production. This is when you discover, as a manager or CEO, that you have to “unlearn” things you thought were taken for granted and this is where you decide to pursue your lean journey – or not.

If you decide to go on, here is a non-comprehensive list of the behavior changes you will have to undertake as a boss once you start regular gemba walks:

- learn to go to a place to see and understand and ask questions but not to make on-the-spot decisions. I personally started to really change my management behavior when I stopped moving forward to the paperboard to take over the discussion.

- while on the gemba, help connect the daily tasks with the overall stake your company is working on: takt time, quality controls, problem-solving and kaizen make sense if you continually promote a focus on the product or service and on the customers.

- pay attention to poor working conditions and to 5S: this is your responsibility, not something you delegate entirely to HR. 5S is poorly understood but of great consequence: as you own your workplace, you will kaizen it.

- thanks to takt time and Kanban cards, your job and that of your managers is no longer to assign tasks to individuals but to support contextual thinking. Support a scientific approach on problem-solving and readily play your role in the chain of support if your teams fail to find a root cause or to reach out to someone who can.

- favor collaboration on transverse issues rather than let your departmental silos create waste, as they work blindly on their own domain optimization. Develop learning rounds so that teams can learn from others and encourage dojos and obeyas to that effect.

- reshape your investment decisions to take into account the customers lead time and key expectations on their side, not solely the OEE (Overall Equipment Effectiveness) of your resources or the decrease of unit costs. Learn to spot and work on the big batches, they increase the customer’s lead time!

AUTHOR BIO: LEAN SENSEI WOMEN

Coming from different continents, horizons and professions, the individuals who form Lean Sensei Women are all recognized lean Senseis, who help companies and organizations build sustainable growth through lean management. They believe in the development of people, respectful of both teams and environment, with a view to produce more value for customers and to society.

Catherine Chabiron: Board Member, Institut Lean France. Author of Notes from the Gemba in Planet Lean and executive lean coach.

Jean Cunningham: Jean Cunningham, a former CFO and LEI board member, is widely recognized for her pioneering work in lean business management systems and the lean office. Her books include Real Numbers, The Value Add Accountant, and Easier, Simpler, Faster.

Rose Heathcote: CEO, Lean Institute Africa. She is the author of Clear Direction and Making a Difference.

Lucy Liu: Currently the Head of Supply Chain Academy for Asahi Beverages, Australia and New Zealand. Over a 28-year stint with Toyota starting at the shop floor, she progressed to management roles include Australia TPS Office and Capability Development Department Manager.

Sandrine Olivencia: Lean sensei and member of Institut Lean France. Specialist in Obeya and product development expert for the digital world.

Cécile Roche: Lean sensei, member of the Institut Lean France, Lean Director of the Thales Group, and author of several books, in particular on Lean in Engineering.

Anne Lise Seltzer: Member of Institut Lean France. Lean Coach in Services and Support functions. Trainer for Lean & Learn at SOL France (learning organization).