Dear Gemba Coach,

We’re struggling with andons. We’ve set up a button for operators to press and call for help, but they’re not using it as much as we hoped, and we don’t know how to make it work properly. Any thoughts?

Have you tried to look at it as a tool for operators?

The benefits of andon are fairly easy to see from a quality system point of view. The andon does a number of things for us:

- It pushes back quality control into the line, with a quality check point at each operation rather than waiting for quality control of the finished work at the end of the line.

- It brings training into day-to-day work as team leaders respond to andon calls and check knowledge of standards and teach operators how to better follow standardized work.

- It increases reactivity as line managers must react quickly to line-down problems rather than continue running the line and fix the problem in their own time.

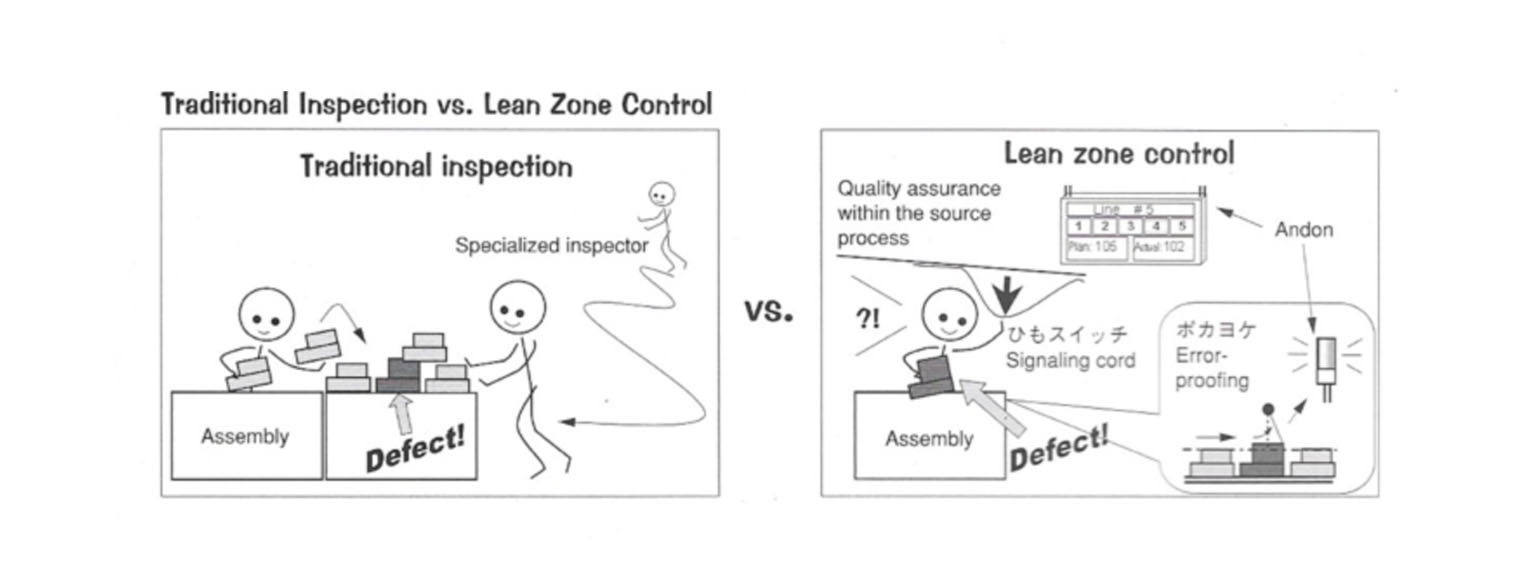

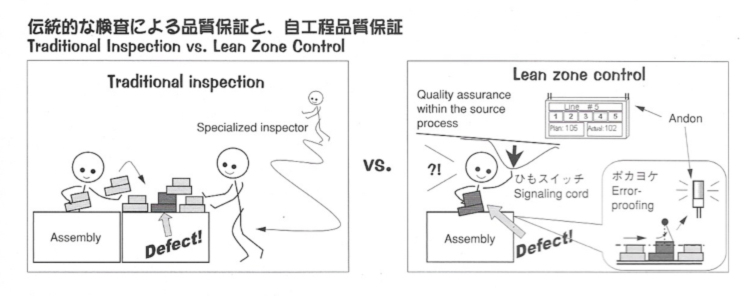

Here’s a great description from Kaizen Express:

Why do so many people struggle with andon then? One common interpretation is that front-line management is unwilling to place itself under such pressure for hourly results. Maybe so, but I fear the problem is deeper than that.

2 Effects

Andon is really a tool for the operators themselves, as most lean tools are.

For instance, when you learn to drive, your instructor teaches you that the main source of danger is speed – you’re handling a two-ton steel object hurtling through time and space. So, when in doubt: slow down. In order to slow down, you’ve got a bake pedal: use it. Most accidents occur simply because we didn’t slow down enough:

- Reckless driving — too close to the next car, too fast, and not realizing that in speed/rain/dark conditions, the reaction time of see/brake/stop is much longer than feels instinctively

- A sudden surprising thing that happens – another car or motorbike you haven’t see coming, something on the road, an unexpected bend and so on, and then reaction time, again, is slower than required.

- Distraction – whether from phoning (it doesn’t feel that way, but your brain really can’t speak and watch at the same time), worse, texting, or simply dozing off.

In any of these instances, the answer is the same: slow down.

If we look at andon for the operator, it acts as a brake pedal to slow down work when something is not right. As a brake pedal it has two effects:

- Calling the team leader when something feels off – the equivalent of slowing down

- Stopping the line if the problem can’t be solved within a minute – stopping the car

What’s in It for Them?

Andon is really a device to give operators greater control over the line itself. But in order to use it habitually, we must realize they face a number of tricky issues such as (1) what cue tells me I should use the andon? (2) What actions does this really trigger? (3) What’s in it for me?

Knowing when to trigger the andon call, whether to pull the chord or push the button, is a very complex problem. Very few companies understand the fabrication process well enough to tell operators what to watch out for, so this is a joint discovery process at first. Much like driving a car, it’s hard to know when you’re driving that you’ve slipped in dangerous territory. Did it start drizzling? Is traffic denser but not blocked yet so that some cars slow down and others try to zip past? Are you being distracted? Is this curve worse than it looks? And so on.

Which is why traffic managers put up road signs, but these become so habitual that we don’t pay as much attention as we should, and even if we do they are often hard to interpret correctly.

If management is not working daily with operators to show interest in understanding what is OK versus what is Not-OK in the process, they will be confused about when to push the andon button and most likely do what we do when we drive: keep on going although we have a nagging feeling we should slow down and look up.

Secondly, what does pushing the button trigger? When we press on the brakes we expect the car to slow down. With andon, this action is more ambiguous. When I press the andon I’m supposed to see the team leader show up in a few seconds. There are two main issues with this effect: (1) does it happen? (2) is this good. You need to be organized so that team leaders actually respond quickly to andon calls, which means dropping what they’re currently working on and rushing to the call site – not easy. Secondly, you’ve got to make sure that when the team leader does show up, the operator sees a friendly face coming towards him or her, and not a grumpy “why are you bothering me again” expression.

Operators need to find out for themselves that by pressing the button, they can (1) affect the line and (2) in a helpful (to them) way. If not, they will very rationally ignore the device and cross fingers hoping that trouble will fall on someone else.

Because, at the end of the day, we do things when we understand clearly what’s in it for us. Ask yourself with brutal honesty: what’s in it for the operator:

- They can do a better job and contribute to the success of the company: when all goes well, this is a great motivator as operators get more control over their line as well as develop mastery in their own tasks. So far, so good. In motivation theory, andon should help with autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

- They can build a better work relationship with their team leader and supervisor by collaborating on problems and looking into standardized work in greater detail, thus also learning more about their own job in the process.

- They can feel they work better with their fellow operators on the line, and not be pointed out when someone down the line spots a defect they should have seen and flagged. Positive peer pressure (still remains pressure) is a powerful influence.

But please notice how each of these motivational points can easily become de-motivators if handled wrong. People can well feel the andon simply puts them on the spot if either team leaders or supervisors react the wrong way.

For the andon to function as its meant to do, operators on the line must experiment with the tool, discover for themselves that indeed, it helps them get ahead by doing a better job and working better with their colleagues. If their personal experience is not conclusive, the andon will not get off the ground. The question, therefore, is what managerial efforts are you deploying to make sure operators have a good experience with the new andon set up?

Building quality into the product is one of the most important lean principles – and andon is a huge part of that. Indeed, how can we hope to hold to takt time if we don’t stop at every defect and try to correct it as fast as we can? And yes, it is difficult to implement because most industrial habits run the way of “keep producing no matter what.” It is precisely because it’s hard that andon must be done with the operators themselves, not to them.

Building a Lean Operating and Management System

Gain the in-depth understanding of lean principles, thinking, and practices.