For years, a key argument in the lean community has focused on whether to focus on tools or on managerial principles. Critics often complain that many of the most popular lean tools have been adopted instrumentally, for short-term gains — point optimization that rarely leads to deeper systematic gains. In our new book, we argue that one key way to view this is to think of lean tools as frames.

Frames structure how we understand a complex situation and scaffold our learning to point us to the next step (as in, literally, the picture frame through which you view the world). The frame, however, doesn’t tell you what you’ll find: you need look through it and see. To understand the essence of lean thinking, it’s critical to see many of what are popularly interpreted as powerful tools as frames. Not as instruments for quick results, but as methods of engagement, understanding, and, yes, framing.

Just-in-time, for example, is a frame stating that we should make only what is needed, when it is needed, and in the amount needed. Taiichi Ohno tinkered for many years with the idea of kanban (cards for each container) to make the frame work. Once kanban was perfected, the just-in-time frame could then be explored in much greater detail.

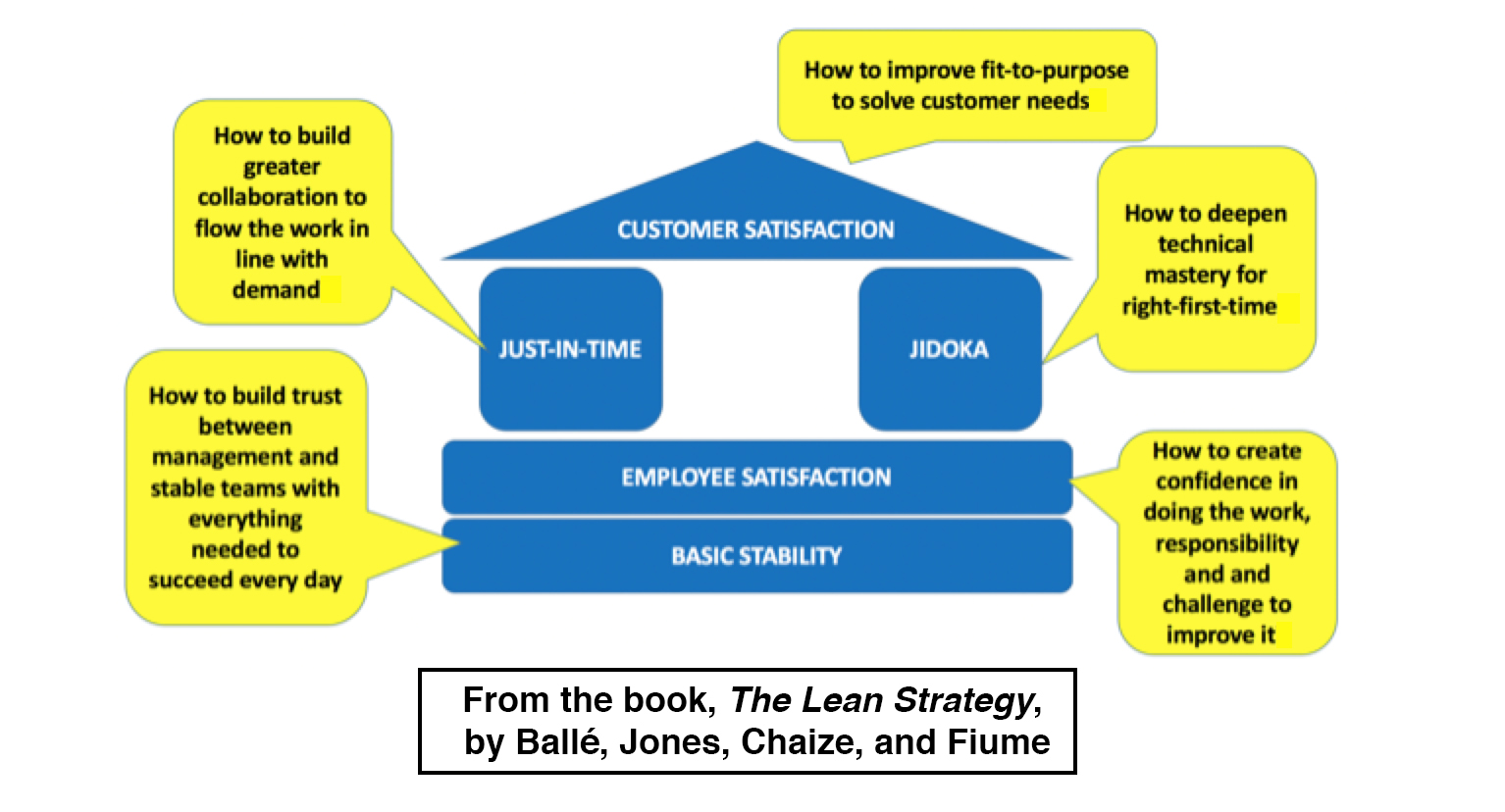

The Toyota Production System (TPS) is in fact a system of a few powerful frames: customer satisfaction, built-in quality, just-in-time, standardized work and kaizen, and basic stability. Within Toyota, the TPS is sometimes called the “Thinking People System.” In remembering his training with Taichi Ohno, Toyota executive Teruyuki Minoura recalled, I don’t think he was interested in my answer at all. He was just putting me through some kind of training to get me to learn how to think.” The system emerged through trial and error in solving practical problems and meeting the needs of the company.

It was only by developing a loose collection of techniques into a full-fledged system that they were able to spread its influence throughout the company, says Minoura. Still, veterans of the early days of teaching TPS repeatedly warn that, in the words of another sensei, the risk with a system of tools is “creating a Buddha image and forgetting to inject the soul into it.” With the tools, the idea remains a fantasy; without the idea the tool leads to the wrong understanding.

The TPS is, in essence, a vast mental scaffolding structure to teach people to think differently, working on the assumption that, as John Shook says, you don’t think yourself into a new way of acting, but you act yourself into a new way of thinking. The TPS defines challenges and exercises to help you understand your own business differently. It’s a learning method, not an organizational blueprint.

Moreover, it’s critical to see these frames as parts of an integrated system. If you want to learn how to think lean, you have to master the lean learning system and the interactions between customer satisfaction, jidoka, just-in-time, and standard work-kaizen. Over the years, I and my fellow authors have seen many people try to sidestep the learning effort by latching on to one specific aspect or tool and reducing the system to a single element. They have indifferent results at best, and disastrous failures at worse. The system is a system because it creates a specific thinking space in which to frame our challenges in a lean way:

The system was developed over decades of trial and error, and it is manifested by specific tools one needs to learn and master, not just in their operations but in their purpose as well.

Executives who have made the learning effort to practice expressing their business challenges in terms of the lean system are constantly impressed with its power to get them to see clearly things that were under their very noses yet they could not grasp before.

In lean thinking, leading from the ground up by practicing “go and see” at the gemba and learning to lead kaizen firsthand guides us to discovering our real problems first and then facing them through creating they key performance indicators that will help us communicate these challenges to the rest of the organization. Then, we use the frames of the lean learning system to progress from facing our challenges to formulating them in lean terms, as well as building the organizational learning conditions needed to seek people-centric solutions. The beauty of this approach is that since learning by doing occurs at the workplace, with real people facing real problems, short-term results are forthcoming all along.

Small “wins” should mark the early trajectory of this learning path. Focusing each person on caring for their customers better and solving operational problems will yield significant short-term results, both financially and in people engagement, even as the full picture remains unclear. The lean strategy balances the needs of today (visible short-term results) with those of tomorrow (sustainable competitive advantage).

Toyota’s specific solutions may not be right for your own department, company, industry. Toyota’s set of improvement frames may not be either, but they are an incredibly powerful way to start. When it’s hard to know what’s what, Toyota’s Thinking People System provides a solid place to start the exploration and inquiry into building our own learning frames—the alternative being making very large, untested gambles. You may not find immediate answers when applying Toyota’s lean learning frames to your situation. But you will form a foundation for learning.

In every case my co-authors and I have seen, this approach proves to be invaluable as the leaders who adopt these frames and make them their own by working with them on their gembas grow and learn to develop their unique, gemba-based way of thinking. Trusting and practicing this approach has proved to be a better way than conventional models of success. Knowing the lean learning frames inside out is not an end in itself. Instead, it’s a necessary first step to acquiring lean thinking and, ultimately, developing one’s own lean learning frames to form solutions with all employees.

Editor’s note: This Post was adapted from content in the book The Lean Strategy, by Michael Ballé, Dan Jones, Jacques Chaize, and Orry Fiume.

As a Lean enthusiast, I found the frame analogy and its usage as a point well made. As Lean practitioners always sturggle for the buy in, I think this will add value to the overall management commitment and support.

Thank you.