I’m sitting here in the Korean Air Lines lounge on my way home from an amazing week where I saw the best automotive plant in the world along with a few of its best suppliers. The Lean Enterprise Institute took 22 people from the U.S., Australia, and Brazil to Fukuoka, Japan to see Toyota Motor Kyushu (TMK). This plant has been voted the J.D. Power platinum award winner for best plant in the world the last two years (and several other times in its history).

Taking people to Japan to see Toyota is not a new thing. Trips like this have been going on for decades. So why do it? Well, one reason is the unique chance to get deep access to how Toyota runs the best plant in the world. Furthermore, this is a plant that struggled back from a period when they were not on top of the pyramid. My former boss, Mr. Hideshi Yokoi, a man with deep TPS experience in both the U.S. and Japan, came here in 2011 to resurrect this great plant.

It’s obvious that he succeeded. The Team Members of Kyushu are deeply engaged in continuous improvement unlike any plant I have seen before. In his opening address to our group on Monday morning, Mr. Yokoi, Plant Manager of the Kyushu Plant, made it clear what his focus was in bringing Kyushu back to its premier status: “Not once did I mention productivity. I focused on quality and safety. Focused on developing capability of the people and productivity followed.”

Someone from the group asked: “Who trained your people?” Mr. Yokoi answered “I did. I went out to the floor, found their struggles and developed their capability to do kaizen.” This prompted someone else to ask: “Where did you start?” Mr. Yokoi answered, “I just went to the floor and looked where they were having struggles and I helped. This was not someone else’s responsibility, it was mine.”

After this initial exchange, we spent two days of deep immersion inside the plant. And each place we went – multiple places in assembly and stamping – we frequently heard the purpose of the improvement to be to increase productivity or reduce costs.

For example, we spent a couple hours in stamping, reviewing the results of a jishuken (a Japanese term for self-study or self-development). The team’s jishuken purpose was driven by the Toyota Motor Kyushu’s overall hoshin goal of reducing costs by 15%. There were other hoshin objectives related to people development and corporate social responsibility, however this team focused for 3 months supporting the corporate goal of 15% cost reduction.

So at the end of the day, several people from our group wondered aloud to their Kyushu hosts: “We heard from Mr. Yokoi that this is not about productivity or cost, but in fact we heard a lot about cost. Yes, we heard about quality and safety too, but cost seemed like a big focus.”

The Toyota Kyushu people didn’t know how to respond to this question. They looked at our group like we’d just landed from Mars rather than the U.S.

So why?

Recently, I’ve heard some people in the lean community say that lean is not about cost reduction. The general story line goes like this: Lean is about developing people – if people are motivated, naturally costs will come out.

But I’d just been through one of the greatest plants in the world and the opposite was true – a consistent focus on cost reduction developed the capability of the people. Tracey Richardson discussed this in her article yesterday.

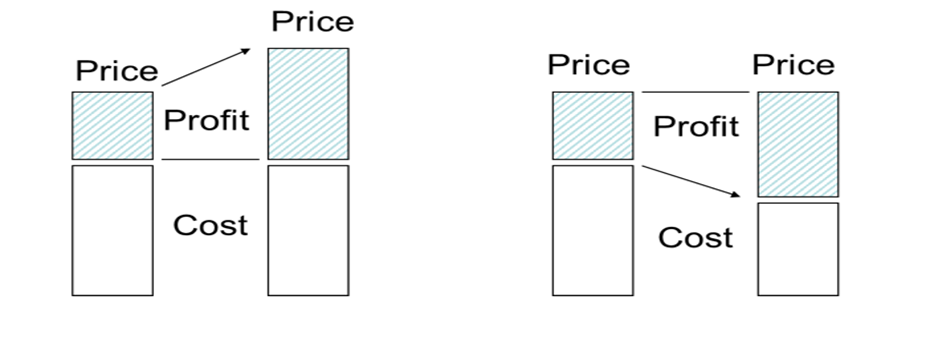

The reality is that Toyota, the company that built TPS, upon which lean is founded, focuses relentlessly on cost. It is such a deep part of their DNA, that when questioned about it, they truly don’t understand the nature of the question. Most of you in the lean community have seen the graphic from Taiichi Ohno (reproduced as the banner art above). Ohno introduced the concept that price is determined by the customer and if we want to increase profit we must reduce cost.

And we can think of cost in two ways: There is cost avoidance and cost reduction.

The stamping jishuken was a great example of cost avoidance. The team knew that demand would increase significantly over the next two years. Given this scenario, many North American companies would immediately think about where to buy good equipment and how to hire the people to support it. They would view that as their problem to solve.

But what we saw in stamping and consistently across each kaizen example at Kyushu, was a relentless pursuit of cost reduction to avoid future costs, by focusing on getting more out of the current machine and taking waste out of people’s work to become more productive. They found the bottleneck in stamping to be the blanking area and the bottleneck there to be changeover, and through 3 months of intensive work they achieved their target.

No new machines.

No hiring of people.

Huge cost avoidance. Doing more with the same or less resources.

And through this process, they developed people’s capability to improve their jobs which greatly motivated the team.

And Kyushu is relentless about cost reduction too. We heard in-depth explanations of karakuri and saw incredible proliferation of this thinking across the assembly plant.

But why do karakuri? One goal is clear – cost reduction. Less expensive machines, less engineering and maintenance resources, less electrical and other utilities for the plant. Of course, because many of the kaizens of karakuri are simpler and require less engineering resources, this type of kaizen motivates the production teams to try things on their own and develops their capability. This is an outcome of the cost reduction activity.

Why do we in the lean world have this aversion to cost reduction as a primary motive of kaizen? Unfortunately, we have seen too many companies focus on kaizen to reduce cost or improve productivity which then the company uses as a weapon to get rid of people. Terrible.

But like many things in Toyota, they see this in the opposite way as the rest of the world. In Toyota’s mind, the continuous pursuit of cost reduction keeps the company strong so that when an economic downturn occurs, they have the financial resources to endure it and they have the flexibility to handle the downturn in production. I was in Toyota during the economic collapse of 2008-09, and Toyota did not lay off anyone in the U.S. even though some plants sat idle for months.

So which is smarter as a business and more respectful of people?

- Train people on lean stuff with the hope that they will find the correct application in their learning in order to solve meaningful problems.

Or

- Establish meaningful problems such as cost reduction at the outset in order to strengthen the business so that people can help grow the business and have job security for a downturn in the economy. And make them feel tied to the success of the company.

For lean to be successful, we should continuously strengthen the business by improving quality, reducing costs, shrinking lead time, and most importantly, as an outcome, developing the capability of our people.